Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 54(3); 2024 > Article

- Research Paper How Do We Approach Quality Care for Patients from Middle Eastern Countries? A Phenomenological Study of Korean Nurses’ Experiences

- Dael Jang, Seonhwa Choi, Gahui Hwang, Sanghee Kim

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2024;54(3):372-385.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24036

Published online: August 31, 2024

2Department of Nursing & Mo-Im Kim Nursing Research Institute, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Artificial Intelligence, College of Computing, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

-

Corresponding author:

Sanghee Kim,

Email: sangheekim@yuhs.ac

- 2,524 Views

- 70 Download

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

Abstract

Purpose

Although more people from Middle Eastern countries are visiting South Korea for medical treatment, Korean nurses lack experience in treating them. Understanding and describing Korean nurses’ experiences can help them provide quality care to these patients by enhancing their competency in culturally appropriate care. This study described the experiences of nurses who provide care to Middle Eastern patients in clinical settings in South Korea.

Methods

We conducted a phenomenological study to describe nurses’ experience of caring for patients from Middle Eastern countries. Ten nurses with prior experience in caring for these patients were recruited from a university-affiliated tertiary hospital. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted between May 1 and June 4, 2020. The transcribed data were analyzed using Giorgi’s phenomenological method to identify the primary and minor categories representing nurses’ experiences.

Results

Four major categories (new experiences in caring for culturally diverse patients, challenges in caring for patients in a culturally appropriate manner, nursing journey of mutual agreement with culturally diverse patients, and being and becoming more culturally competent) and 11 subcategories were identified.

Conclusion

Nurses experience various challenges when caring for Middle Eastern patients with diverse language and cultural needs. However, nurses strive to provide high-quality care using various approaches and experience positive emotions through this process. To provide quality care to these patients, hospital environments and educational programs must be developed that center on field nurses and students and support them in delivering quality care while utilizing their cultural capabilities.

Published online Aug 05, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24036

How Do We Approach Quality Care for Patients from Middle Eastern Countries? A Phenomenological Study of Korean Nurses’ Experiences

Abstract

Purpose

Although more people from Middle Eastern countries are visiting South Korea for medical treatment, Korean nurses lack experience in treating them. Understanding and describing Korean nurses’ experiences can help them provide quality care to these patients by enhancing their competency in culturally appropriate care. This study described the experiences of nurses who provide care to Middle Eastern patients in clinical settings in South Korea.

Methods

We conducted a phenomenological study to describe nurses’ experience of caring for patients from Middle Eastern countries. Ten nurses with prior experience in caring for these patients were recruited from a university-affiliated tertiary hospital. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted between May 1 and June 4, 2020. The transcribed data were analyzed using Giorgi’s phenomenological method to identify the primary and minor categories representing nurses’ experiences.

Results

Four major categories (new experiences in caring for culturally diverse patients, challenges in caring for patients in a culturally appropriate manner, nursing journey of mutual agreement with culturally diverse patients, and being and becoming more culturally competent) and 11 subcategories were identified.

Conclusion

Nurses experience various challenges when caring for Middle Eastern patients with diverse language and cultural needs. However, nurses strive to provide high-quality care using various approaches and experience positive emotions through this process. To provide quality care to these patients, hospital environments and educational programs must be developed that center on field nurses and students and support them in delivering quality care while utilizing their cultural capabilities.

INTRODUCTION

The easy access to and development of medical technology in South Korea have led to an increase in the movement of foreign patients, resulting in a growing influx of patients from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds [1, 2]. There has been a consistently increasing trend of foreign patients visiting South Korea since it was legally allowed to attract foreign patients in 2009; the number of accumulated patients surpassed two million in 2019, increasing from approximately 320,000 in 2017 to approximately 490,000 in 2019. Furthermore, there has been an ongoing recovery in this growth trend following the downturn during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Among the foreigners seeking medical services in South Korea, there has been growing interest in people from the Middle East, who belong to the so-called “halal market” [4].

Recently, Middle Eastern patients have demonstrated a growing preference for South Korea as an overseas treatment destination. This trend can be attributed to the local expansion of South Korean hospitals, excellent medical technology and services, and lower medical costs than those in Western countries [5]. The number of patients from the Middle East has significantly increased from 2,035 in 2009 to 30,869 in 2022, which is a 15-fold increase. Moreover, 13.9% of these Middle Eastern patients opt for inpatient treatment compared to the total foreign patient population [3]. The proportion of medical expenses covered by patients in the United Arab Emirates is progressively increasing, establishing them as significant targets for medical services. This suggests that nurses in Korea are increasingly likely to provide care for Middle Eastern patients. Thus, nurses must consider patients’ sociocultural context.

When encountering patients with different cultural characteristics of the Middle East, Korean nurses may face diverse challenges, compared with those caring for patients from Korea [6]. Cultural characteristics of Middle Eastern patients such as halal dietary practices, hijab culture, religious practices, and gender-based customs are unique characteristics Korean nurses have not experienced yet, and failure to recognize them in advance can lead to inconvenience or misunderstanding between patients and healthcare providers [7]. To respect their culture, foreign studies are trying to comprehensively identify various phenomena that may occur while providing medical services to Middle Eastern patients through qualitative research [8, 9, 10]. As a result of the study, even in the West, where cultural diversity is relatively high, it has been shown that they do not receive the person-centered treatment they deserve due to a lack of understanding of Islamic cultures [11]. Because the proportion of the population adhering to Islam in South Korea is only 0.4%, Koreans have not had much experience of getting to know more about Islamic cultures. Consequently, Korean nurses may experience greater challenges when caring for patients from Middle Eastern countries, primarily because of religious factors, compared with other foreign patients [6]. Nurses’ lack of preparedness to understand the needs of foreign patients can result in complaints regarding communication, culture, and education [12]. Nurses may also experience communication problems and situations in which they do not meet the expectations of foreign patients regarding medical services [6]. Communication problems can lead to misunderstandings about treatment procedures and complaints and affect patient satisfaction and quality of care [12]. In previous studies, it has been reported that not sufficiently understanding patients from different cultures affects the clinical competency of nurses, which can negatively affect patients’ health [13].

To mitigate patient dissatisfaction because of cultural differences, it is necessary to understand and consider possible variations in cultural sensitivity based on individuals’ cultural backgrounds and the healthcare system. Domestic nurses in South Korea which are mainly composed of single ethnic groups, often possess limited knowledge and skills in caring for foreign patients owing to the homogeneous nature of the country, which leads to elevated levels of anxiety among nurses [14]. Moreover, few nurses have completed a cultural competency curriculum [14, 15], and there is a lack of shared guidelines or regulations at the hospital level, resulting in confusion in nursing practices and a dearth of cultural nursing competency programs [16]. Moreover, it has been reported that nurses’ cultural competency curriculum, cultural competence, and intercultural communication related to foreign patients affect patients’ health problems such as nurses’ basic nursing skills, physical assessment skills, and education skills for patients [16]. However, existing studies in South Korea have primarily focused on medical tourism, English-speaking patients, and multicultural patients. There is a lack of research on patients from Middle Eastern countries [6, 17]. The experience of caring for patients in different cultures is not simply a phenomenon that can be measured and confirmed quantitatively [18]. The cultural and social contexts are complexly comprehensive, and the process of sufficiently understanding and considering the phenomenon through a phenomenological method is necessary. Through this, it is possible to understand what kind of process nurses who care for Middle Eastern patients experience while nursing them and based on this, what is needed to provide quality care.

Therefore, we comprehensively explored the experiences of nurses working in clinical settings in tertiary hospitals in Korea vis-à-vis providing quality care to Middle Eastern patients. This allowed us to gain insights into their efforts and overall performance. Overall, the present study provides fundamental insights that may contribute to improving the quality of nursing services provided to Middle Eastern patients in Korea.

METHODS

1. Research design

We conducted a phenomenological study to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of South Korean nurses who provide care for Middle Eastern patients in domestic clinical settings.

2. Participants

The participants were nurses with experience in caring for Middle Eastern patients at a tertiary hospital in the past year. The scope was limited to tertiary hospitals because 53.5% of Middle Eastern patients in South Korea sought healthcare services from facilities of this kind, as indicated in the Middle East Medical Use Statistics [19]. Staff nurses, excluding chief nurses who manage nursing units and newly qualified nurses with less than one year of clinical experience, were recruited to participate in this study. Snowball sampling was used to select the participants. A post was shared on the bulletin board of Yonsei University College of Nursing, attended by several nurses working in tertiary hospitals. Subsequently, individuals who expressed an interest in participating were interviewed. If data saturation was not achieved, participants were introduced to other potential participants. Initially, 12 individuals were recruited, but two declined to participate owing to their limited experience in caring for patients from the Middle East; the final sample comprised 10 participants working in various tertiary hospitals.

3. Data collection

1) Interview guide development

The interview guide was developed through a comprehensive review of the relevant literature using the method proposed by Kallio et al. [20]. This method is the process of identifying the prerequisites for using semi-structured interviews, using previous knowledge, formulating the preliminary guide, pilot testing the guide, and then finalizing the guide. The interview guide consisted of semi-structured questions categorized as introductory, essential, and concluding questions. Additionally, open-ended questions were used to gather comprehensive insights from participants. Introductory question is “When and where have you gained experience nursing Muslim patients from Middle Eastern countries?”. Key questions probed the specific experiences of individual nurses caring for patients from the Middle East and aspects of the hospital system. The researchers finished by asking “What do you believe you will need to provide care for Muslim patients from Middle Eastern countries?”.

2) Interviews

Data were collected from May 1 to June 4, 2020, through one-on-one interviews. Interviews were conducted by three researchers within the team, and guidelines were followed. Interviews allow researchers to deeply explore a participant’s experiences and perceptions, identify new concepts or problems [21] and enhance the richness of the qualitative research design. Semi-structured and open interview guides were used to avoid restricting responses and to allow participants to communicate freely. Each interview lasted approximately one hour, while additional interviews were conducted with four participants as required, depending on the participants’ feedback.

3) Data analysis

Giorgi’s phenomenological research method [22], a method frequently used in qualitative research, was conducted. Researcher transcribed all the recorded data, and the contents were recorded in field notes within two days. According to the Giorgi’s analysis procedure [22], the first step was to get a sense of the whole and grasp the content by repeatedly reading all the transcribed contents together with all the researchers who participated in the interview. If the content was ambiguous, participants sought clarification to ensure the accuracy of the interview. Second, in order to reflect the meaning of the participant’s experience as it is, the work of repeatedly reading and distinguishing the various meaning units described by the participants was repeated. Third, the researcher transformed the meaning units into academic terms while maintaining a phenomenological attitude so as not to deviate from the essence of the phenomenon. Similar concepts were grouped to derive subcategories by examining the similarity and differences of meaning units, and similar concepts were grouped and classified into 11 subcategories. In the fourth step, each derived central meaning was integrated and classified, and the meaning of the experience grasped from the participant’s point of view was described in four categories. Researchers repeatedly read the meaning of the experience identified from the perspective of all participants, repeatedly analyzed and rearranged, and tried to find the structure of the overall experience. Based on these results, the researchers examined nurses’ experiences caring for Middle Eastern patients by examining the relationship between the content of each category and the meanings of other categories. This process was conducted to ensure rigorous qualitative research, minimize subjectivity, and rely only on the data obtained from the interviews.

4) Researchers’ training and preparation

The principal investigator responsible for the research guidance for this study has expertise in qualitative research methodologies, has taught relevant courses in graduate programs, and has delivered lectures on qualitative research. The researchers have abundant experience in workshops, academic conferences, and qualitative research projects. Further, the researchers who conducted the interviews had more than five years of experience as general nurses in internal, surgical, or specialized tertiary hospital wards, which enabled them to understand the situations and meanings reported by the participants. Additionally, the researchers completed a qualitative research methodology class as part of their Doctor of Philosophy courses. They continue to enhance their skills through regular research meetings and exploration of qualitative research published in various fields.

5) Rigor of the research results

To ensure rigor, efforts were made to increase the strictness of the four aspects suggested by Guba & Lincoln [23]. To ensure credibility, the researchers aimed to form a trusting relationship with the participants, enabling a better understanding of their experiences before the interview and ensuring reliable data. Field notes were prepared within 20 minutes of each interview to interpret the data, while peer reviews were conducted based on the initial analysis of the interview data to mitigate any preconceptions held by the researchers. If there was an ambiguous expression, the participants’ opinions were checked and reflected. The three researchers read all the scripts repeatedly several times to try to understand the subject’s experience as much as possible. To ensure transferability, in-depth descriptions of the research content, researcher roles, participant recruitment, data collection, general characteristics of participants, and analytical methods are provided. For consistency, it was faithfully implemented according to the Giorgi’s process [22]. Through regular meetings, researchers derived meaning units, organized categories, reaffirmed the contents, discussed differences in analysis results, and reached an agreement. Finally, confirmability was ensured by continuously receiving feedback from one researcher who is very proficient in qualitative research and is teaching qualitative research.

4. Ethical consideration

Before conducting this study, ethical approval was obtained from the Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (no. Y-2020-0046). The researchers confirmed the nurses’ intentions to participate and considered their preferred places and times to ensure comfort. Before each interview, the participants were asked to read the study description and provide their written informed consent. They were informed that the interview data would be used only for research purposes and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were also informed that the interview contents would be recorded for analysis, which was performed only after prospective participants provided their consent. The collected data were stored on a researcher’s password-protected computer to restrict access.

RESULTS

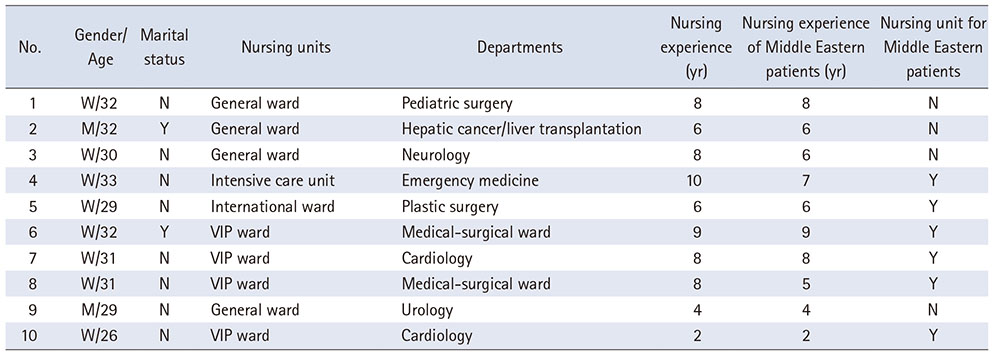

1. General characteristics of participants

Table 1 presents the participants’ general characteristics. The sample comprised 10 participants, eight women (80.0%) and two men (20.0%). The types of nursing units varied: Four worked in general wards (40.0%), four in very important patient wards (40.0%), one in an intensive care unit (10.0%), and one in an international ward (10.0%). Nine participants worked in adult wards, whereas one worked in a pediatric unit. The nursing units covered various specialties, including three surgical units (liver cancer and transplant wards, plastic surgery, and urology), two internal medicine units (neurology and cardiology), and three covered others (internal surgery mixed wards and emergency medicine). The participants had 2~10 years of nursing experience, with an average of 6.9 years. Six (60.0%) worked in nursing units with beds assigned to Middle Eastern patients.

Table 1

General Characteristics of Participants

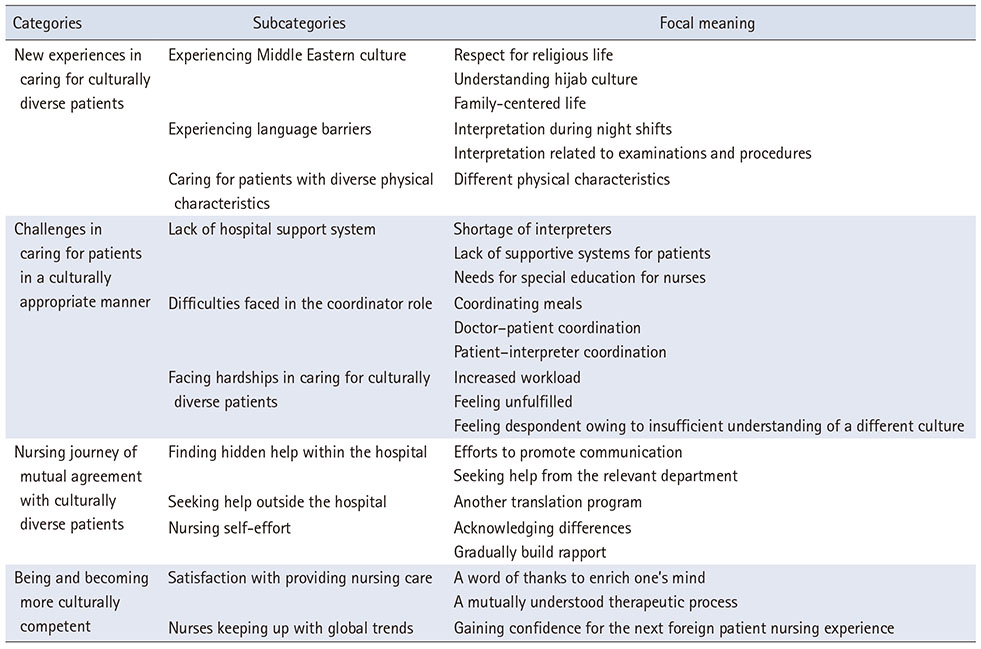

2. Results of analysis

Phenomenological research method analysis was conducted to identify key findings from the data. Through this analysis, 23 focal meanings were constructed by integrating similar content from the participants’ statements through repeated reading. The focal meanings were then compared to identify commonalities and differences, creating a single relevant group and four main categories with 11 subcategories (Table 2).

Table 2

Categories of Nurses’ Experiences in Caring for Patients from Middle Eastern Countries

1) Category 1: New experiences in caring for culturally diverse patients

Caring for patients from foreign cultures is a new experience for all participants. Through this, nurses experienced Middle Eastern culture for the first time, faced language barriers, and cared for patients with characteristics more diverse than those of domestic or non-Middle Eastern foreign patients.

(1) Experiencing Middle Eastern culture

The nurses experienced Middle Eastern culture, coming into contact with patients’ religious practices, hijab culture, and family-centered habits. Several Middle Eastern patients adhered to the rules of living outlined by Islamic principles, observing religious customs such as daily prayer, segregation between genders, and dressing modestly—which involves wearing a headscarf or burqa (a head and face covering). As no treatment could be performed during prayer times, nurses respected this practice by adjusting their nursing workflow or examination schedules or by marking prayer times outside the patient’s room. In keeping with their customs, female patients were unable to meet male medical staff or visitors during hospitalization if they were not wearing their hijab, thus requiring the nurse-in-charge to understand and pay special attention to this aspect. In addition to such modesty practices, several other areas required nurses to communicate with and treat patients—for example, prohibiting conversations and preventing physical contact with men other than family members. Furthermore, Middle Eastern patients generally have a family-centered culture; thus, several caregivers or visitors often visit them in the hospital.

“They often ask me not to come in at specific times because they have to pray.” (participant 5) Respect for religious life

“I was making the rounds at night. I received no response when I knocked on the door. I had to knock a few times before going inside the room. I think they were strict about meeting men without hijabs. She was surprised (about the situation in which she faced a man without a hijab).” (participant 9) Understanding hijab culture

“Even if the patient is a woman, the medical personnel are sometimes men, so you have to wait for them to put on their hijab so the doctors do not see their face.” (participant 5) Understanding hijab culture

“Middle Eastern patients are similar to Korean patients because they want their families to take care of them. This is also a family-centered culture. In Korea, one main caregiver stays and takes care of the patient; however, in the case of Middle Eastern patients, there seem to be approximately two or three main caregivers at all times.” (participant 5) Family-centered life

(2) Experiencing language barriers

Nurses experienced language barriers while communicating with and caring for Middle Eastern patients. Notably, participants reported these barriers in the evening or night, when translation services were less available than during the day. These barriers often lead to various issues in forming trust with patients and sharing information related to treatment, including examinations and procedures.

“As there is no interpreter at night, there are times when the patient’s pain is too severe; however, at that time, it is difficult to communicate, so no matter how much medicine you give them or try to explain, patients often become anxious because the information is meaningless to them.” (participant 6) Interpretation during night shifts

“Even if you try to arrange an exam or surgery, it is literally impossible without an interpreter, and you have to explain everything step-by-step. Koreans understand several things even if they are explained roughly, whereas foreign patients have several difficulties in understanding such explanations; therefore, the procedure must be explained by an interpreter first.” (omitted: participant 10) Interpretation related to examinations and procedures

(3) Caring for patients with diverse physical characteristics

During the nursing process, nurses face physical characteristics that differ from those of domestic patients. As the patients’ skin color differed, the nurses expressed that it took more time to administer intravenous injections, test for antibiotic skin reactions, and check for pressure ulcers. Further, most hospitals provide additional air-conditioning devices owing to the low heat tolerance of Middle Eastern patients. Additionally, patients’ dressings do not remain intact for long periods because of excessive sweating.

“As their skin is a bit different, it is difficult for me to read the Antibiotic Skin Test. I cannot see it well even if I mark it, and I cannot identify redness as well.” (participant 1) Different physical characteristics

“They often bring their own portable air conditioners. There are also several complaints about how they cannot withstand the heat in Korea.” (participant 3) Different physical characteristics

2) Category 2: Challenges in caring for patients in a culturally appropriate manner

In the process of providing quality nursing care to culturally diverse patients, nurses experience various challenges, such as a lack of hospital support system from the hospital and difficulties faced in the coordinator role. Consequently, nurses caring for culturally diverse patients often face various hardships.

(1) Lack of hospital support system

The support systems for Middle Eastern patients differ across hospitals. Nurses expressed disappointment when such support systems were insufficient. A shortage of interpreters and staff support, a lack of supportive systems (such as manuals or consent forms) for patients, and the need for a special education for nurses were some of the specific issues that contributed to this disappointment.

“It would be nice to have an X-ray in Arabic, but there is no such thing, so interpreters have to go back and forth between the patient and the healthcare personnel because there is a lack of interpreters and staff. If a Middle Eastern patient is hospitalized, it would be nice to have a protocol.” (participant 1) Shortage of interpreters , Lack of supportive systems for patients

“Curriculum is also important. This is because several Middle Eastern patients visit Korean hospitals. Although I rarely care for Middle Eastern patients, I hope to receive training to understand foreign patients or share examples of mistakes made by other nurses.” (participant 2) Needs for special education for nurses

(2) Difficulties faced in the coordinator role

The nurses served as coordinators and connected various departments, including interpreters, doctors, laboratories, nutrition departments, and transfer staff during patient hospitalization. Additional tasks include handling meal requests and assigning interpreters to various schedules. Additionally, although the participants’ hospitals had interpreters, it was difficult to assign them if doctors did not arrive at the scheduled time. Changes or delays often resulted in complaints from patients and related departments directed toward nurses.

“Other foreigners have many options, but it is very difficult to provide a treatment meal with a halal meal.” (participant 9) Coordinating meals

“If the translator does not answer the phone, you have to keep calling. Moreover, you must make sure the patient understands what you are saying. It can take a long time for these patients to communicate effectively. As an intermediary, you have to arrange all of this (interview with doctor), which is difficult when you are busy.” (participant 7) Doctor-patient coordination

“Depending on the work, I have to adjust my schedule around the patient and interpreter, which takes a long time.” (participant 5) Patient-interpreter coordination

(3) Facing hardship in caring for culturally diverse patients

Nurses experience hardships when caring for culturally diverse patients owing to the increased workload. Although the number of patients assigned to each nurse remained the same, caring for those who required additional assistance weighed heavily on nurses’ minds. Nurses felt unfulfilled and despondent because they could not form strong connections with culturally diverse patients because of their lack of understanding of Middle Eastern cultures.

“I think other nurses are having a hard time, too. Watching the team struggle becomes a burden.” (participant 2) Increased workload

“Even for patients who have a difficult time, when communication goes well, the difficulties disappear and I feel accomplished. However, foreign patients cannot communicate, so I do not feel a sense of accomplishment because of the lack of communication.” (participant 1) Feeling unfulfilled

“Even if work is hard, I feel a sense of accomplishment when patients express it. But Middle Eastern patients don’t have that and never shake hands with a female nurse. So, I feel discouraged. I don’t think anyone thanked me. I don’t know the culture, but⃛” (participant 1) Feeling despondent owing to insufficient understanding of a different culture

3) Category 3: Nursing journey of mutual agreement with culturally diverse patients

Nurses are committed to providing care to culturally diverse patients by actively seeking services supported by hospitals and utilizing resources outside the hospital. Additionally, the nurses tried to provide the best care possible.

(1) Finding hidden help within the hospital

Although the hospitals had support systems in place, there were varying levels of awareness and usage of these resources among nurses within the same hospital. While beginners were often unable to utilize these support systems because of a lack of awareness, most nurses used the available support systems to improve communication and receive help from other departments.

“They gave me a booklet, called a communication card, which contained pictures with Arabic text underneath. If the patient is experiencing pain, there is a picture that depicts pain with the word ‘pain’ written in Arabic, so I showed it to the patient like this [acting out the scenario], so it was acceptable.” (participant 6) Efforts to promote communication

“Interpreters leave work at 9 or 10 p.m.; therefore, if there are any questions or problems, they make rounds to check on patients in advance so that there are no complaints during the night.” (participant 6) Seeking help from the relevant department

(2) Seeking help outside the hospital

The nurses also identified external support systems that were useful in caring for Middle Eastern patients. Most of them used free translation applications, most using Google Translate.

“Few Middle Eastern patients speak English, so they often only speak Arabic, and even if they speak English, they rarely speak it fluently. Thus, patients often use Google Translate and similar applications.” (participant 5) Another translation program

(3) Nursing self-effort

In addition to utilizing internal and external support systems when caring for culturally diverse patients, nurses also highlighted their individual efforts. They acknowledged the cultural, physical, and religious differences among patients from the Middle East while providing nursing care. They consciously tried to improve their communication skills and learn the patients’ language to establish rapport with them.

“A simple greeting, consideration, and understanding of cultural practices; for example, if the hijab is slightly off, we adjust it so it is properly put on. There are things that they are very grateful for.” (participant 4) Acknowledging differences, Gradually build rapport

4) Category 4: Being and becoming more culturally competent

Nurses acquired new experiences and faced challenges in providing quality nursing care to patients from other cultures. They eventually experienced satisfaction in caring for these patients and improved their cultural competence throughout their caregiving journey.

(1) Satisfaction with providing nursing care

The participants felt rewarded by the patients’ gratitude. When nurses treated Middle Eastern patients and understood them as individuals, patients expressed a deep sense of satisfaction with the care provided.

“It is rare to have someone say ‘thank you’ when you leave the hospital after surgery⃛I feel proud just by thinking about it, and I think that was the proudest moment for me as a healthcare worker.” (participant 2) A word of thanks to enrich one’s mind

“It’s a life where people live [laughs], so we have something in common. I think we became closer by talking about our sons. I think I was able to get closer to the patient—woman-to-woman, mother-to-mother—by empathizing with her emotionally, not as a Middle Eastern patient but as any other patient, which improved the patient-nurse relationship.” (participant 6) A mutually understood therapeutic process

(2) Nurses keeping up with global trends

Nurses gained confidence and improved their understanding of cultural differences while experiencing and resolving various situations in the process of providing care to culturally diverse patients. This enabled them to keep up with global trends in nursing and healthcare based on the needs of diverse patient populations.

“I have always provided care only to Korean patients, but it was rewarding to care for foreign patients.” (participant 4) Gaining confidence for the next foreign patient nursing experience

“It was difficult because I did not have experience with Middle Eastern culture. Now that I have [cared for Middle Eastern patients] many times, I think I can do it easily.” (participant 3) Gaining confidence for the next foreign patient nursing experience

DISCUSSION

We conducted a phenomenological study to comprehensively understand South Korean nurses’ experiences in caring for patients from the Middle East. The nursing experiences were divided into four categories and 11 subcategories.

In line with Category 1, nurses have come into contact with different cultures that are uncommon in South Korea. Patients’ cultural characteristics and beliefs are deeply embedded in the daily lives of Middle Eastern patients through practices such as eating halal food and daily prayer [6, 7]. Their commitment to these practices continues during hospitalization, which often affects the treatment process. Thus, a deeper understanding of these patients’ lives and cultures is essential for leading them to perform appropriate health promoting behavior and to provide quality care [6, 7]. Oakley et al. [18] studied the experience of non-Muslim nurses caring for Muslim patients providing end of life care, and nurses focused on clinical care and did not embrace cultural practices that were important to them, which has been shown to contribute to increased stress for both nurses and caregiver. Therefore, hospitals should provide nurses with transcultural education and support to provide quality care that considers cultural diversity in caring for these patients. In addition, nurses have reported difficulties in performing nursing, such as identifying skin redness, pressure sore classification, and antibiotic skin test results due to differences in physical characteristics. These difficulties negatively affect the patient’s health and hinder quality care [6]. Therefore, their physical assessment education should be provided, as well as education about their culture.

In the present study, nurses reported being concerned about verbal communication errors when caring for Middle Eastern patients, particularly at night, when interpreter services are limited. Communication-related problems have long been reported by nurses caring for foreign patients [17, 24, 25, 26]. Research findings are similar to those of a previous study [12] reporting that the demand for “interpretation services” is the highest for tasks that require the efficient provision of nursing services to foreign patients. Problems in communication can lead to misunderstandings about treatment procedures and complaints and can negatively affect their health [12]. Therefore, language can represent a barrier to providing them with appropriate nursing care, so hospitals that treat Middle Eastern patients need to have sufficient manpower for interpretation. Intervention studies are mainly conducted for patients with different languages in countries with many immigrants, and in the Netherlands, where a quarter of the population has a migration background, it contributed to health promotion through educational videos produced in their language while being culturally sensitive to Islam to prevent the impediment of medical information provision due to lack of communication [27]. If interpreters cannot reside in hospitals 24 hours a day, producing and using video education materials in their languages could also be a good way to improve the quality of care.

In line with Category 2, despite the frequent hospitalization of patients from other cultures, nurses sometimes experience disappointment because of the lack of interpreters and the absence of proper support systems for them and for nurses. These findings are similar to those of Min [28], which reported that nurses experience negative emotions such as burden, embarrassment, and confusion when nurses care for foreign patients without adequate support in an unprepared situation. Additionally, Jang & Lee [17] reported emotions such as “disappointment,” consistent with the present study. Additionally, the nurses expressed that they did not feel a sense of accomplishment owing to their increasing workload, lack of communication, and lack of understanding of other cultures. These emotions were particularly evident in participants who provided higher-intensity nursing services to culturally diverse patients in situations in which emotional exchanges were hindered by communication barrier. Similarly, Min [28] noted the issue of nurses’ reduced self-esteem because of limited nursing skills. Therefore, it is necessary to prevent negative emotions by applying interventions such as simulation programs to nurses to promote an understanding of Middle Eastern culture before caring for patients. In a study that applied simulation program of United Arab Emirates patient to nursing students, it has been demonstrated that students’ cultural competence and level of empathy for patients have been significantly improved and can raise awareness of cultural diversity and improve quality of care [29].

In Category 2, nurses coordinate schedules with doctors and other departments, pay attention to various areas, such as providing halal meals, and experience increased workload due to various additional tasks. Many studies have already reported that nursing foreign patients takes more time and requires more workload than nursing domestic patients [6]. Now, it is necessary to systematically improve this problem by conducting research that specifically calculates which nursing works are additionally implemented and how much more time is required [30]. Based on severity, there is a study that categorizes direct nursing care, indirect nursing care, and personal time to identify workload and appropriate ratio of nurse staffing [31]. Based on these studies, the nursing of foreign patients should also be systematically analyzed, and appropriate nursing staff arrangements should be supported.

In line with Category 3, domestic hospitals attracting foreign patients have implemented measures to ease the communication burden on nurses, including establishing international clinics and dedicated coordinators [32, 33]. Nurses actively promote communication and provide optimal care with the help of interpreters and nutrition teams. However, the availability of hospital support services and nurses’ satisfaction with them vary depending on their resource utilization ability. This finding is consistent with previous studies involving patients from other cultures. Park et al. [24] investigated the work experience of nurses caring for foreign patients and found that satisfaction levels varied depending on the nurses’ resource utilization ability. Additionally, a study by Kim [34] on employees working in customer contact departments found that job resource identity affects job burnout and customer-oriented behavior. Thus, nurses who consistently aim to secure resources and identify hidden support services are more likely to experience positive outcomes when caring for culturally diverse patients. Resource utilization ability depends on how effectively hospitals inform and educate nurses about the support system [24]. Therefore, hospitals must provide continuous information so that nurses can accurately grasp the support system and easily access it. Hospitals that lack appropriate support systems should consider sharing resources through interhospital systems or increasing support through continuous demand surveys.

In the present study, nurses made an effort to form trusting relationships with their patients and provide emotional support and physical resources. Specifically, they strived to respect cultural differences by not interfering with prayer times, preparing for visits in advance, and using Arabic greetings or other expressions to empathize with patients. Moreover, this study indicated that when nurses respect the patient’s culture and exhibit communication-related goodwill, a trusting bond is formed and patients feel grateful [12]. Therefore, it is essential to implement effective hospital-level measures to improve communication and encourage a culture of respect by developing in-house signs and brochures and improving interpretation services [35]. In Japan, a study was conducted for nursing students, including diversity standardized patient simulation, which care patients of different cultures and religions, in the curriculum [36]. As a result, even students who had never encountered Muslim patients expressed that they opened their eyes to how to communicate with patients from other cultures, and this education promoted culturally competent nurses and increased self-efficacy for performing intercultural nursing skills. Learning attitudes that respect other cultures and preparing to empathize will be important in providing quality care by establishing trust relationships with patients in hospitals later.

Finally, participants reported experiencing personal growth by caring for culturally diverse patients. The nurses expressed that they derived the most satisfaction from patients’ expressions of gratitude, which fostered a sense of homogeneity; nurses saw patients as human beings and acknowledged and understood their differences. The bond between nurses and patients significantly influences the nurses’ satisfaction and sense of achievement [37]. The positive effects of forming bonds with patients are not limited to the same culture. Nurses caring for foreign patients also experience satisfaction and pride in weathering challenges [24]. Nurses who gained a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction through this process confirmed that their cultural competency had improved and that they felt more confident in subsequently caring for culturally different patients.

Cultural competency refers to the ability to recognize the cultural background of others and provide nursing care suitable to their cultural context by accepting and respecting different cultures [38]. Nurses’ cultural competencies in caring for foreign patients eventually affect their clinical performance [39, 40]. However, education and institutional support to increase clinical nurses’ cultural competency are still lacking. Therefore, there is a need for educational and training programs that focus on improving nurses’ cultural knowledge and skills [41]. Specifically, the quality of nursing care for culturally diverse patients should be improved through specialized nursing education based on the patients’ cultural backgrounds. Additionally, the International Council of Nurses Code of Ethics for Nursing, revised in 2021, “Nurses and Global Health” encourages nurses to collaborate globally to develop and maintain global health and emphasizes the globalization of nurses [42]. As nursing has become increasingly globalized, education for nurses with cultural competencies is needed for patients from various cultural backgrounds. Therefore, it is necessary to encourage nurses to keep up with international trends through systematic support and professional education in hospitals.

This study has the following limitations. First, in this study, nurses from various hospitals participated, but there may be bias in selecting subjects by posting a recruitment announcement at one graduate school and recruiting subjects through snowball sampling. Second, data collection was conducted only in the form of 1:1 interview rather than using various data collection methods in consideration of the nature and characteristics of the phenomenon to be studied. However, it is meaningful in that study supports education and institutional improvement needs for improving cultural competence and skills by deeply analyze the experience of nurses analyze the experiences of nurses caring for Middle Eastern patients, that have been lacking in domestic research. Through the study, it was confirmed that caring and considering for Middle Eastern patients based on in-depth understanding of the culture and customs of Middle Eastern is to provide quality care for them. Through this quality care, patients engage in desirable health promotion behaviors, empathize with each other, and improve nurse’s competency. If cultural competence is not supported, it may negatively affect the health outcome and satisfaction of the patients, and it may also affect the clinical ability of nurses, making it impossible to provide quality care. Therefore, it is significant that it identified what is providing quality care based on cultural competence and how nurses overcame difficulties and provided quality care and that it suggested the direction of field and research in the future.

CONCLUSION

We explored the experiences of nurses caring for patients from the Middle East. The findings confirmed the experiences of nurses caring for Middle Eastern patients, the challenges they faced, the treatment journey with these patients, and nurses’ ability to become better nurses. Nursing experiences with patients from the Middle East pertained to both personal and systemic aspects, indicating a growing need for improvement.

To provide optimal nursing care to Middle Eastern patients, it is necessary to improve nurses’ cultural competence and understand their unique cultural characteristics. This involves establishing a hospital environment in which nurses can deliver high-quality care while utilizing their cultural capabilities. Furthermore, it is important to develop an education program centered on field nurses and students to address and minimize the cultural shock experienced by nurses while providing care to patients from foreign cultures. Such educational measures can aid in improving the overall cultural competence of nursing students and practicing nurses, thus leading to improved nursing care for culturally diverse patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: Jang D & Choi S & Hwang G & Kim S.

Data curation or/and Analysis: Jang D & Choi S & Hwang G.

Funding acquisition: Jang D & Kim S.

Investigation: Jang D & Choi S & Hwang G.

Project administration or/and Supervision: Jang D & Kim S.

Resources or/and Software: Jang D & Choi S & Hwang G.

Validation: Jang D & Choi S & Kim S.

Visualization: Jang D & Choi S & Kim S.

Writing original draft or/and Review & Editing: Jang D & Choi S & Hwang G & Kim S.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

References

-

Eom T, Yu J, Han H. Medical tourism in Korea–recent phenomena, emerging markets, potential threats, and challenge factors: A review. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 2019;24(6):563–573. [doi: 10.1080/10941665.2019.1610005]

-

-

Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI). Statistics on international patients in Korea, 2019 [Internet]. KHIDI; 2020 [cited 2023 Nov 17].Available from: https://www.khiss.go.kr/board/view?pageNum=1&rowCnt=10&no1=8&linkId=175804&menuId=MENU00308&schType=1&schText=%EC%99%B8%EA%B5%AD%EC%9D%B8%ED%99%98%EC%9E%90&boardStyle=&categoryId=&continent=&schStart-

Char=&schEndChar=&country=.

-

-

Battour M, Ismail MN. Halal tourism: Concepts, practises, challenges and future. Tourism Management Perspectives 2016;19(Pt B):150–154. [doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2015.12.008]

-

-

Kang YK. Middle Eastern medical tourists are coming [Internet]. Midas: 2015 [cited 2023 Nov 17].Available from: http://www.yonhapmidas.com/article/151209165629_

449768.

-

-

Kim S, Jin KN, Min H. Factors affecting nurses’ stress: Focusing on foreign patient relationships. Korean Public Health Research 2017;43(2):11–19. [doi: 10.22900/kphr.2017.43.2.002]

-

-

Suk SS. Design strategy for the attraction of patients of the medical tourism industry in Korea – emphasis on the Muslim patient medical services. Journal of Digital Design 2016;16(1):1–10.

-

-

Ryu YJ, Lee YM. Influence of cultural competency and intercultural communication on clinical competence of emergency unit nurses caring for foreign patients. Journal of Korean Critical Care Nursing 2021;14(1):40–49. [doi: 10.34250/jkccn.2021.14.1.40]

-

-

Ahn JW, Jang HY. Factors affecting cultural competence of nurses caring for foreign patients. Health Policy and Management 2019;29(1):49–57. [doi: 10.4332/KJHPA.2019.29.1.49]

-

-

Choi YK, Ahn JW, Kim KS. Influence of cultural competency, intercultural communication, and organizational support on nurses’ clinical competency caring for foreign patients. Health and Social Welfare Review 2018;38(4):518–543. [doi: 10.15709/hswr.2018.38.4.518]

-

-

Jang HY, Lee E. Caring experiences of the nurses caring for foreign inpatients of non-English speaking. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 2016;17(12):415–426. [doi: 10.5762/KAIS.2016.17.12.415]

-

-

Oakley S, Grealish L, El Amouri S, Coyne E. The lived experience of expatriate nurses providing end of life care to Muslim patients in a Muslim country: An integrated review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2019;94:51–59. [doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.03.002]

-

-

Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI). Statistics on international patients in Korea, 2018 [Internet]. KHIDI; 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 14].Available from: https://www.khidi.or.kr/board/view?menuId=MENU00085&linkId=48806593.

-

-

Giorgi A. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 1997;28(2):235–260. [doi: 10.1163/156916297X00103]

-

-

Guba EG, Lincoln YS. In: Effective evaluation: Improving the usefulness of evaluation results through responsive and naturalistic approaches. Jossey-Bass; 1981. pp. 411-423.

-

-

Park HS, Ha SJ, Park JH, Yu JH, Lee SH. Employment experiences of nurses caring for foreign patients. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 2014;20(3):281–291. [doi: 10.11111/jkana.2014.20.3.281]

-

-

Kim JR. In: Transcultural nursing experiences among Korean nurses in the United Arab Emirates hospital [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Ewha Womans University; 2018. pp. 1-92.

-

-

Lee BS, Kim MY. Nursing experience of delivery care for married immigrant women in Korea: An application of focus group interview. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 2015;16(6):3999–4010. [doi: 10.5762/KAIS.2015.16.6.3999]

-

-

Hamdiui N, Bouman MPA, Stein ML, Crutzen R, Keskin D, Afrian A, et al. The development of a culturally sensitive educational video: How to facilitate informed decisions on cervical cancer screening among Turkish- and Moroccan-Dutch women. Health Expectations 2022;25(5):2377–2385. [doi: 10.1111/hex.13545]

-

-

Min J. Hospital nurses’ multicultural patient care experience. Journal of the Korean Society for Multicultural Health 2018;8(1):31–43.

-

-

Kim Y, Kim K, Park MM, Kim IS, Kim MY. A study on the appropriateness of health insurance fee in main nursing practices. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research 2017;23(2):236–247. [doi: 10.22650/JKCNR.2017.23.2.236]

-

-

Park YS, Song R. Estimation of nurse staffing based on nursing workload with reference to a patient classification system for a intensive care unit. Journal of Korean Critical Care Nursing 2017;10(1):1–12.

-

-

Suk SS, Jun SJ. A study on the information design reflecting the characteristics of Arab culture - for Muslim patients from the Middle East who visited Korea. Journal of Korea Design Forum 2020;25(3):179–192. [doi: 10.21326/ksdt.2020.25.3.016]

-

-

Suk SS, Shin DJ. Medical communication design strategy for Middle East patient. Journal of Brand Design Association of Korea 2017;15(4):203–216. [doi: 10.18852/bdak.2017.15.4.203]

-

-

Kim MS. The effects of job-resourcefulness on the relationship among job demand, burnout, and customer oriented behaviors: Moderating effects of job-resourcefulness. Journal of Business Research 2015;30(3):209–231. [doi: 10.22903/jbr.2015.30.3.209]

-

-

Chun KJ, Choi JH, Kim YR, Lee SO, Chang CL, Kim SS. The effects of both shift work and non-shift work nurses’ empathy on life and job satisfaction. Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2017;17(3):261–273. [doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2017.17.03.261]

-

-

International Council of Nurses (ICN). The ICN code of ethics for nurses [Internet]. ICN; 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 6].

-

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite