Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 54(3); 2024 > Article

- Research Paper Temporal Exploration of New Nurses’ Field Adaptation Using Text Network Analysis

- Shin Hye Ahn, Hye Won Jeong, Seong Gyeong Yang, Ue Seok Jung, Myoung Lee Choi, Heui Seon Kim

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2024;54(3):358-371.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24034

Published online: August 31, 2024

2College of Nursing, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea

-

Corresponding author:

Seong Gyeong Yang,

Email: hyewon1129@ut.ac.kr

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to analyze the experiences of new nurses during their first year of hospital employment to gather data for the development of an evidence-based new nurse residency program focused on adaptability. Methods: This study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in Korea between March and August 2021 with 80 new nurses who wrote in critical reflective journals during their first year of work. NetMiner 4.5.0 was used to conduct a text network analysis of the critical reflective journals to uncover core keywords and topics across three periods. Results: In the journals, over time, degree centrality emerged as “study” and “patient understanding” for 1 to 3 months, “insufficient” and “stress” for 4 to 6 months, and “handover” and “preparation” for 7 to 12 months. Major sub-themes at 1 to 3 months were: “rounds,” “intravenous-cannulation,” “medical device,” and “patient understanding”; at 4 to 6 months they were “admission,” “discharge,” “oxygen therapy,” and “disease”; and at 7 to 12 months they were “burden,” “independence,” and “solution.” Conclusion: These results provide valuable insights into the challenges and experiences encountered by new nurses during different stages of their field adaptation process. This information may highlight the best nurse leadership methods for improving institutional education and supporting new nurses’ transitions to the hospital work environment.

Published online Aug 21, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24034

Temporal Exploration of New Nurses’ Field Adaptation Using Text Network Analysis

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to analyze the experiences of new nurses during their first year of hospital employment to gather data for the development of an evidence-based new nurse residency program focused on adaptability.

Methods

This study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in Korea between March and August 2021 with 80 new nurses who wrote in critical reflective journals during their first year of work. NetMiner 4.5.0 was used to conduct a text network analysis of the critical reflective journals to uncover core keywords and topics across three periods.

Results

In the journals, over time, degree centrality emerged as “study” and “patient understanding” for 1 to 3 months, “insufficient” and “stress” for 4 to 6 months, and “handover” and “preparation” for 7 to 12 months. Major sub-themes at 1 to 3 months were: “rounds,” “intravenous-cannulation,” “medical device,” and “patient understanding”; at 4 to 6 months they were “admission,” “discharge,” “oxygen therapy,” and “disease”; and at 7 to 12 months they were “burden,” “independence,” and “solution.”

Conclusion

These results provide valuable insights into the challenges and experiences encountered by new nurses during different stages of their field adaptation process. This information may highlight the best nurse leadership methods for improving institutional education and supporting new nurses’ transitions to the hospital work environment.

INTRODUCTION

In 2022, the turnover rate of new nurses in Korea increased from 47.7% in 2021 to 52.8%, and the rate of resignations within one year of appointment also increased from 15.6% to 17.9% [1]. The most common reason for turnover was work maladjustment [1]. New nurses may resign from their positions if they find it hard to adapt to clinical life or struggle with the stress of working in a hospital [2]. In general, new clinical nurses must adapt to clinical work while caring for patients. This makes the transition from student to nurse challenging and stressful [3]. Previous studies have reported that new nurses experienced a reality shock due to differences between their expectations and the reality of the clinical environment during their third month of hospital work [4].

Maladjustment among new nurses arises from a complex interplay of factors, including inadequate communication skills with both patients and health personnel, suboptimal job performance, and the burden of work responsibilities [5, 6, 7]. These challenges can significantly hinder their ability to adapt to the clinical environment, impacting both their personal growth and patient care outcomes [8]. Providing a structured educational framework, nurse residency programs (NRPs) contribute positively to enhancing retention rates, competency, self-confidence, and the quality of patient safety [8]. However, in the context of South Korea, NRPs typically span an average of 57.3 days, markedly shorter than the 6-month to 1-year programs commonly reported internationally [9]. This discrepancy underscores the urgent need for NRPs tailored to the unique healthcare landscape of Korea.

Moreover, reflective journaling about clinical experiences offers a powerful tool for new nurses to introspect and navigate their adjustment to clinical duties. Engaging in self-reflection allows them to explore their experiences, including their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, fostering personal and professional growth [10]. Nurse educators play a pivotal role in guiding and mentoring this reflective process, thereby enhancing workplace adaptability [11]. Within the nursing context, such reflective practices not only promote professional development but also lead to improved patient care and outcomes [10]. The analysis of self-reflection diaries from new nurses can provide valuable insights into the root causes of maladjustment and turnover, offering directions for enhancing their professional experiences [10, 11, 12, 13].

Text network analysis (TNA) can be used to analyze self-reflection diaries written by new nurses with the intention of strengthening their adaptability to clinical practice. TNA is useful for exploring information and phenomena within documents, identifying trends, and suggesting future research directions [14]. Thus, a TNA of self-reflection diaries can offer insights useful for understanding learners’ characteristics, needs, and priorities and thus for developing effective educational programs. TNA has been used in a variety of disciplines to explore knowledge structures, quantify key research concepts, and identify contextual structures [15]. Recently, scholars in the field of nursing used TNA to analyze the knowledge structure of specific topics, such as pain management and trends in nursing informatics [14, 15]. However, most existing research on new nurses’ experiences is qualitative and exploratory, often relying on interviews and surveys for data collection [7, 16].

Although scholars have already explored how to reduce turnover among new nurses and help them better adapt to the clinical field, these studies have often involved nurses who had started working within the last year without classifying them by period [17, 18]. However, the difficulties new nurses face after joining a hospital change over time [7]. Educational programs designed to help new nurses adapt to hospital work should involve a step-by-step fostering strategy that considers their development across different working periods.

This study aimed to analyze the critical reflection journals in which new nurses recorded their clinical experiences during the three periods of their first year working at a hospital: specifically, 1~3, 4~6, and 7~12 months into hospital work. We expect the findings to reveal new nurses’ educational needs and provide insights into how NRPs can be tailored to better prepare new nurses for clinical practice.

METHODS

1. Study design

This was a quantitative content analysis study using TNA to extract keywords from the reflection journals of new nurses throughout their first year of hospital work.

2. Participants and data collection

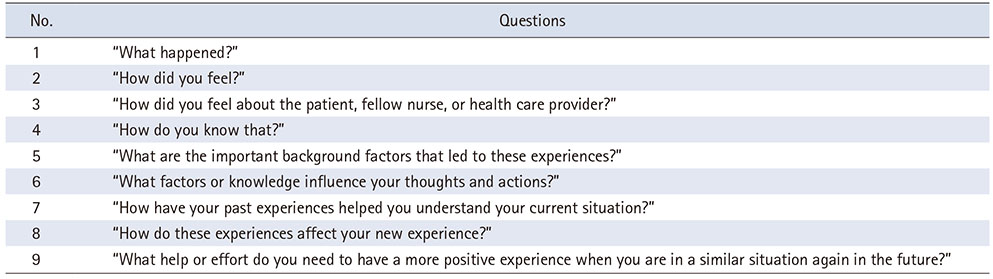

The research was conducted at a tertiary hospital that integrates a growth program for new nurses within their first year of employment. In this study, the experiences of new nurses were investigated according to different stages of their tenure. Based on the period of highest reality shock at 4 months [19] and the period affecting the retention intention, which is the clinical experience at 7 months [20], the timeline was divided into three phases: 1~3 months, 4~6 months, and 7~12 months. This program includes writing critical reflective journals on an online platform (Padlet), aimed at fostering their professional development. During the orientation for new nurses, a 30 minutes session is conducted to explain the growth program, emphasizing the importance and methodology of maintaining a reflective journal. To facilitate reflective journaling, we provided the new nurses with prompts derived from previous studies [21], encouraging them to engage in critical inquiry throughout their journal entries (Table 1). New nurses were encouraged to document their experiences in journals throughout the year, making entries five times in the initial 1~3 months, four times during the subsequent 4~6-month period, and five times in the final 7~12 months. Critical reflective journals are written under pseudonyms along with department names; thus, specific individuals cannot be identified without the use or combination of additional information. Pseudonymous information can be used without individual consent for research and statistical processing purposes [22]. The contents of the journals were only visible to the nurses and the clinical nurse educators. This assured the new nurses that they could write honestly and without pressure from their nursing manager or preceptor.

Table 1

Critical Inquiry Guide

This study involved a retrospective analysis of critical reflective journals written by new nurses who commenced their employment between March and August 2021. Initially, 90 new nurses maintained online reflective journals as part of their growth program. However, 10 of these nurses were excluded from the final analysis because they resigned from their positions. Consequently, the journals from 80 participants, with personal information anonymized, were included in the final analysis. To facilitate the analysis, we downloaded the journals into Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft) using the export function.

3. Data analysis

We used NetMiner 4.5.0 (Cyram Inc.) to analyze the journal data across the preprocessing stage, network formation process, network statistical analysis and visualization state, and sub-theme analysis stage. In the data preprocessing stage of this study, word extraction and purification were conducted by three members of the research team (ASH, YSK, and JUS), while network creation and analysis were performed by a nursing professor (JHW). The team members had an average of 13.5 years of clinical experience and 4.3 years of experience in training nurses. The selection and analysis of content were based on a profound understanding of the challenges faced by new nurses. Using the query function, words occurring less than twice were excluded from the analysis. This study transformed the 2-mode network of “document-word,” which lists keywords appearing in reflective journals, into a 1-mode network in the form of “keyword-keyword,” representing the frequency of co-occurrences between main keywords as links in a word network. Subsequently, to establish a network comprising only links that met a certain standard, a network was created that included only the proximity distance (window size) within two words and a co-occurrence frequency of two or more. The detailed methodology for data analysis is outlined as follows.

4. Pre-processing stages

Once we downloaded the journals into Microsoft Excel 2019, we formed a journal database. From these data, we only extracted nouns from long texts using the morphological analysis function in NetMiner 4.5.0. We read the data and extracted morphemes using the import unstructured text menu. In the word purification process, we categorized words with similar meanings together (forming a thesaurus), identified compound words as defined words, and labeled irrelevant or common words as excluded words, ultimately leading to the creation of a “user dictionary” through a collaborative agreement among researchers.

First, we used natural language processing to exclude words without significant meanings (e.g., pronouns, adjectives, adverbs) [23]. During this process, we collected words with similar meanings in a thesaurus. Word phrases composed of two or more words were read as a single semantic unit; that is, as defined words. Common words and stopwords unrelated to the study were excluded and registered in the user dictionary based on our agreement [23]. Regarding words that had similar meanings but were expressed differently, we carefully checked the selection of representative words and the pre-registration of similar words [24]. Meanwhile, we performed word purification through multiple discussions to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased interpretation of the data. These sessions were dedicated to scrutinizing the relevance and neutrality of words, eliminating ambiguous terms, and achieving consensus on the contextually appropriate meanings of specific phrases used in the journals. In the 1~3-month period, 80 thesaurus, 83 defined words, and 1,388 excluded words were registered in the user dictionary, and a total of 333 words were extracted and refined. In the 4~6-month period, 140 thesaurus, 328 defined words, and 2,229 excluded words were registered in the user dictionary, and a total of 405 words were extracted and refined. In the 7~12-month period, 140 thesaurus, 133 defined words, and 1,649 excluded words were registered in the user dictionary, and a total of 355 words were extracted and refined. For instance, in the thesaurus, the terms “code blue,” “cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),” and “chest compression” were designated as “CPR.” In the defined words, proper nouns and compound nouns composed of two or more morphemes, such as “tracheal intubation” and “oxygen saturation,” were set such that they could be recognized as one word. In the case of excluded words, such as “teacher,” “fact,” “two days,” and “meanwhile,” it was determined that these words lack significant meaning and therefore should be excluded from the analysis. For each period, the top 30 words were extracted to identify core keywords, and NetMiner 4.5.0 was used for analysis.

5. Process of network formation

A co-occurrence matrix of keywords was created through the two keywords appearing in one sentence or between other keywords [15]. Repeated co-occurrence may yield a semantic structure; here, the higher the degree of connection, the more meaning structures in various contexts appear to co-occur with many different keywords in the one-mode matrix of the co-occurrence of the keywords’ relationship. To identify major phenomena in network analysis appropriate degrees of connection among keywords were set based on the ease of interpreting the research results and visualizing the network; a standard connection value was not proposed [15]. In the analysis, 236 keywords were extracted for the 1~3-month period, 185 keywords for the 4~6-month period, and 177 keywords for the 7~12-month period, each with a degree of connection of 2 or more.

6. Network statistical analysis and visualization

We used a one-mode matrix for our statistical analysis and visualization to discover core keywords for each journaling period. Regarding network centrality, we analyzed degree centrality, and confirmed the average and concentration of centrality. “Degree centrality” is the degree to which nodes in a network co-occur based on the degree of connection [25]. To visualize the main semantic structure, we created a sociogram with the top 30 keywords.

7. Sub-theme analysis

To identify sub-thematic groups, we extracted the largest component based on cohesion, and then divided the aggregated group into optimal subgroups using an eigenvector community analysis. If the modularity had a negative value, the community was not significantly divided; if the value was 0, then all nodes belonged to one community; if the value was greater than 0, then it was somewhat modularized (the larger the value, the better is the community structure) [26].

8. Ethical consideration

Before the investigation, ethical approval was acquired from the Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hospital (IRB No. CNUH-2022-313) and the Department of Nursing. All data collected during the study period was used for research purposes only, anonymized to protect personal information, and stored securely to prevent unauthorized access. Considering the pseudonymization of information, the study proceeded without obtaining individual consent from the research subjects. This procedure aligns with the ethical standards for scientific research, which allow for the use of pseudonymized data in research and statistical analysis without requiring explicit consent from participants.

RESULTS

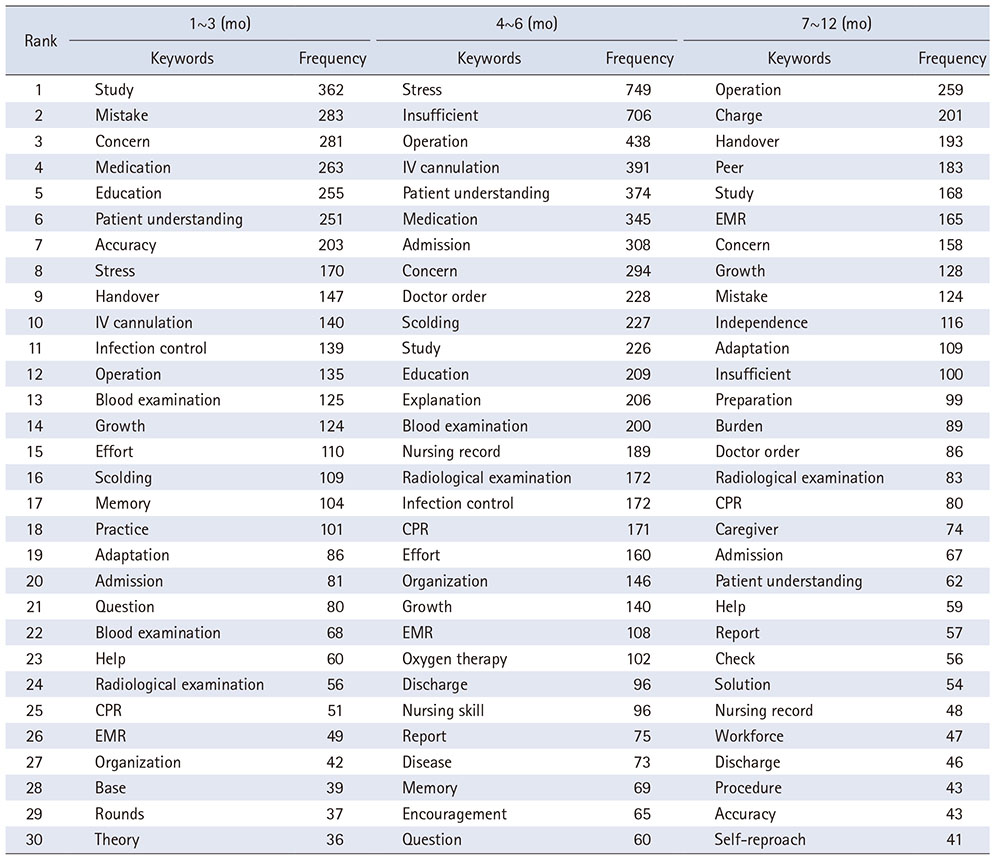

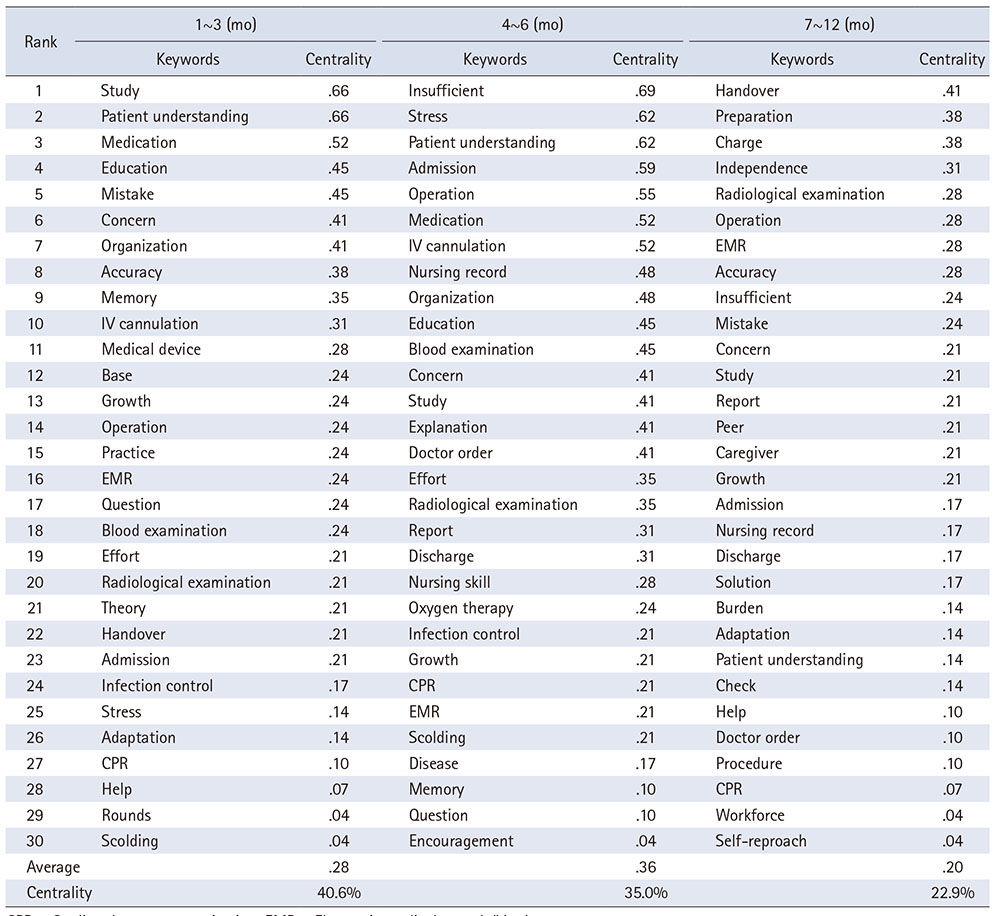

1. Keywords from the journals

We analyzed the top 30 keywords for simple frequency and degree centrality to determine the core keywords of the journals by time period. We analyzed the experiences of the new nurses during the 1~3-, 4~6-, and 7~12-month periods of their first year of hospital work. In descending order of overall frequency over time, the keywords “study,” “mistake,” “concern,” “medication,” and “education” appeared most frequently in the 1~3-month period. During months 4~6, “stress,” “insufficient,” “operation,” “Intravenous (IV) cannulation,” and “patient understanding” were most frequent. During months 7~12, the keywords “operation,” “charge,” “handover,” “peer,” and “study” appeared most frequently (Table 2). The average degree centrality of the word networks over time were .28, .36, and .20, respectively; the concentrations were 40.6%, 35.0%, and 22.9%, respectively (Table 3). Regarding degree centrality from 1 to 3 months, the order was “study,” “patient understanding,” “medication,” “education,” and “mistake.” Regarding degree centrality from 4 to 6 months, the order was “insufficient,” “stress,” “patient understanding,” “admission,” and “operation.” Regarding degree centrality from 7 to 12 months, the order was “handover,” “preparation,” “charge,” “independence,” and “radiological examination.” The keywords derived only during the 1~3-month period of the year were “medical device,” “base,” “practice,” “theory,” and “rounds.” The keywords derived only during the 4~6-month period were “explanation,” “nursing skill,” “oxygen therapy,” “disease,” and “encouragement.” The keywords derived only during the 7~12-month period were “preparation,” “charge,” “independence,” “peer,” “caregiver,” “solution,” “burden,” “check,” “procedure,” “workforce,” and “self-reproach.”

Table 2

The Frequency of the Top 30 Keywords in the Journals

Table 3

The Degree Centrality of the Top 30 Keywords in the Journals

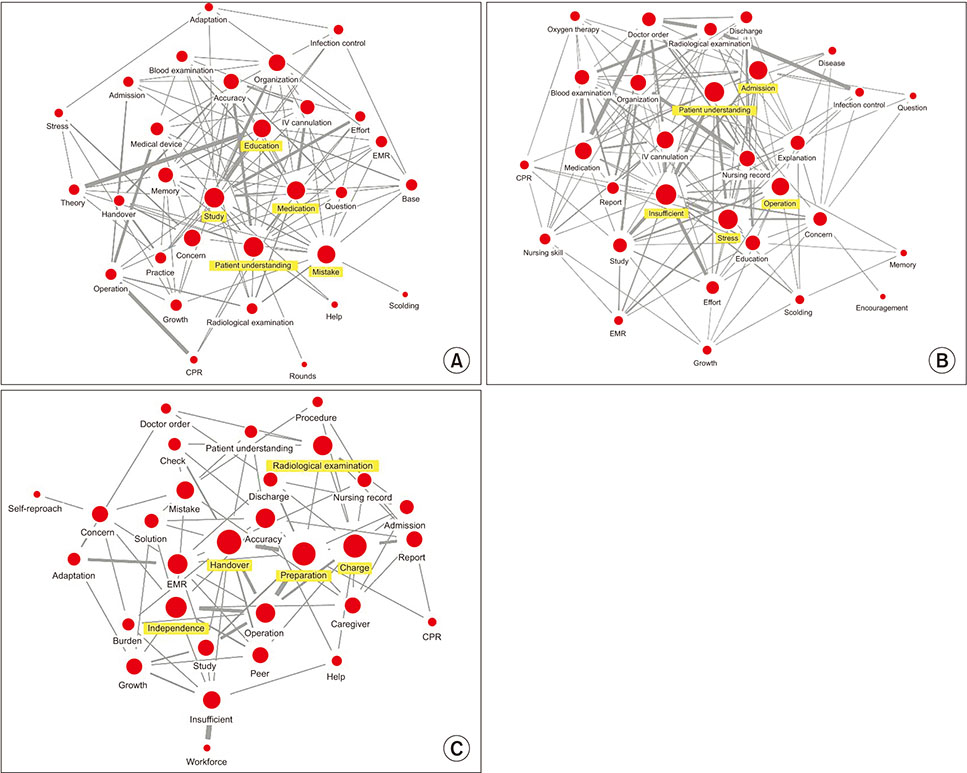

2. Visualizing the main semantic structure

Based on our network analysis of the journals, we generated sociograms (graphs consisting of nodes and links), including the top 30 keywords by time period (Figure 1). In examining the semantic structure, we focused on the words with the highest degree of centrality for each period. Based on a connection strength of 3 or higher, “study-education,” “study-effort,” “study-organization,” “study-medication,” “study-memory,” “study-mistake,” “study-accuracy,” “study-patient understanding,” “patient understanding-accuracy,” and “patient understanding-medication” were identified as semantic structures from 1 to 3 months. Next, “insufficient-study,” “insufficient-effort,” “insufficient-patient understanding,” “insufficient-stress,” “ insufficient-IV cannulation,” “insufficient-admission,” “insufficient-concern,” “insufficient-operation,” “insufficient-electronic medical record (EMR),” “insufficient-scolding,” and “insufficient-explanation” comprised the semantic structure from 4 to 6 months. Finally, “handover-preparation,” “handover-operation,” “handover-peer,” and “handover-check” formed the main semantic structure from 7 to 12 months.

Figure 1

CPR = Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMR = Electronic medical record; IV = Intravenous. Yellow highlight indicates the degree centrality of the top 5 nodes.

Keyword network analysis derived from the critical reflective journals across three time periods.

(A) 1~3 months. (B) 4~6 months. (C) 7~12 months.

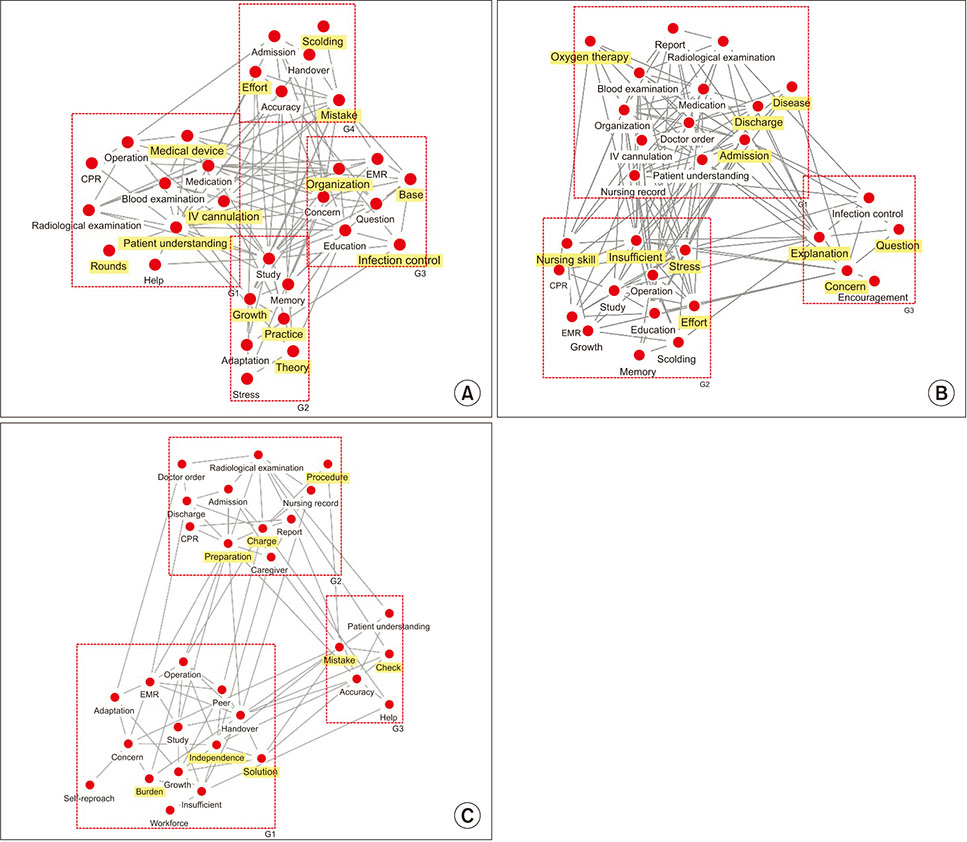

3. Sub-thematic groups

The eigenvector community analysis is based on cohesion in the keyword network by time period (Figure 2). During the initial 1 to 3 months, it was divided into four subthemes, and the modularity was .19. We named the subthemes based on the contexts in which their keywords were used, as follows: main clinical nursing practices for understanding patient conditions (“rounds,” “IV-cannulation,” “medical device,” “patient understanding”), learning and professional growth (“theory,” “practice,” “growth”), fundamental nursing and safety (“base,” “infection control,” “organization”), and scolding for mistakes and efforts to perform accurately (“scolding,” “mistake,” “effort”). During the 4~6-month period, it was divided into three sub-themes, and the modularity was .18. Considering the contexts in which the keywords of each subgroup were used, we named the sub-themes as follows: new nurses’ routine work (“admission,” “discharge,” “oxygen therapy,” “disease”), experience of overcoming stress due to lack of clinical nursing skills (“insufficient,” “stress,” “effort,” “nursing skill”), and concern about explanation work (“concern,” “explanation,” “question”). In the subsequent 7~12 months, it was divided into the following three sub-themes, and the modularity was 0.31: burden due to insufficient work performance after independence (“burden,” “independence,” “solution”), beginning of nursing work as a nurse in charge (“preparation,” “procedure,” “charge”), and checking to reduce mistakes (“check,” “mistake”).

Figure 2

CPR = Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMR = Electronic medical record; G1~4 = Group 1~4; IV = Intravenous. Yellow highlight refers to words uniquely derived from each period.

Visualization of sub-theme analyses of the critical reflective journals for different time periods.

(A) 1~3 months. (B) 4~6 months. (C) 7~12 months.

DISCUSSION

We examined the clinical experiences of new nurses across three phases of their first year of hospital work based on insights from their online critical reflective journals. Our analysis reveals distinct themes and challenges unique to each phase, emphasizing the evolving nature of their adaptation and learning experiences.

During their first three months working in the hospital, new nurses confront a myriad of challenges that profoundly shape their early professional experiences. In the journals written by new nurses, a noticeable gap was observed between the theoretical knowledge acquired during their education and its actual application in clinical settings. The journals also confirmed a willingness among these nurses to learn and grow as experts. However, due to unfamiliar tasks and the use of medical equipment, frequent mistakes were made. These errors led to corrective feedback from senior nurses and highlighted the need for continued efforts to reduce mistakes. Prior research corroborates this finding, indicating that new nurses often perceive themselves as unqualified professionals due to inadequate knowledge and skills, a sentiment that is most acute during the first two months of their practice [27]. This phenomenon has been attributed to the challenges in training and securing clinical practice instructors for Korean nursing students, and to a clinical practice approach that emphasizes observation over active practice [28]. Nevertheless, despite these initial challenges, the emergence of the keyword “growth” during this period indicates a determination to surmount these obstacles and evolve professionally. During this period, educational programs are primarily conducted for preceptor education and the acquisition of theoretical knowledge [28, 29]. Consequently, there is a need to harmonize theoretical knowledge with practical application to foster an environment where nursing skills can be methodically honed through simulation-based education and comprehensive manuals detailing essential clinical nursing competencies [30]. However, most medical institutions in Korea lack simulation centers for nurse education, indicating a need for government support to improve the education system and ensure high-quality education.

In addition, new nurses experienced difficulties using the unfamiliar EMR system, and frequent errors were noted due to insufficient patient understanding during the handover process. To address these issues, they emphasized the importance of conducting thorough rounds in their journals. This aligns with the findings of a study indicating that new nurses, at the onset of their employment, were not accustomed to EMR and experienced significant stress primarily associated with task performance [7]. In order to facilitate effective adaptation to each hospital’s EMR system, it is essential to provide practical computer training from the initial stages of employment and to establish a more systematic and integrated adaptation process. This process should include a mentoring program to understand the difficulties faced by new nurses and to discuss improvement strategies tailored to individual characteristics. A study that provided a mentoring program to newly graduated nurses highlighted its significance in transitioning to a nurse role and offered a career opportunity to develop new nursing competencies from a mentor [31]. Such a system is essential to understand the challenges encountered by new nurses and to offer guidance tailored to each nurse’s unique circumstances. Comprehending the experiences of new nurses during this initial period is necessary to develop strategies that foster their resilience, competency, and well-being. Currently, many medical institutions in Korea are implementing clinical nurse educator projects. Therefore, it is necessary to utilize the clinical nurse educators to develop and implement a mentoring program tailored to the characteristics of each institution.

During their first 4 to 6 months of hospital work, new nurses confront evolving challenges that mark a significant phase in their professional growth. This period is marked by an in-depth understanding of their roles and responsibilities, accompanied by a critical self-assessment of their skills and competencies. In this phase, new nurses often perceive their “nursing skills” as “insufficient,” which can cause them to experience feelings of “stress.” This sentiment is echoed in a journal entry by a new nurse: “After gaining independence and caring for patients on my own, the demands placed on me are overwhelming, yet my skills do not seem to improve, causing me significant stress.” This reflects a discrepancy between the abilities of new nurses and the high standards expected in clinical settings. According to previous research, after 4 months of employment, it is the time to work independently, and new nurses’ organizational commitment significantly decreases and burnout increases [32]. In particular, when job competency, such as clinical performance, has not significantly grown, the burden, fear, and anxiety due to excessive work increase, and negative feedback increases, which adds to stress [32, 33, 34]. In the Korean context, new nurses are often assigned a heavy workload and face challenges before they acclimate to their roles due to the constraints of the new nurse education program [28]. In Korea, the typical education programs for new nurses focus predominantly on the technical aspects of nursing tasks and procedures, with less emphasis on emotional support and coping mechanisms for stress management [35]. New nurses’ perceived lack of empathy is notably linked to lower job satisfaction and a higher intention to leave the position, further highlighting the need for emotional support alongside practical training [36]. There is a lack of studies directly assessing the effectiveness of emotional support programs for new nurses, highlighting a significant gap in current training protocols. Given these challenges, there is a pressing need for a supportive educational environment tailored to the unique needs of new nurses. Such an environment should not only aim to bridge the gap in technical skills but also provide emotional support through structured programs that address the psychological aspects of transitioning into a demanding and often stressful role.

During this period, new nurses increasingly participate in complex procedures and are often required to explain medical conditions and treatments to patients or their guardians. This not only demands a higher level of procedural knowledge but also necessitates strong communication skills to ensure that explanations are clear and accurate. The appearance of keywords such as “explanation” and “concern” suggests that new nurses not only execute tasks but are also involved in educating patients, which requires a comprehensive understanding of medical conditions and treatments. Research indicates that continual skill acquisition is vital for new nurses. Prior research has similarly noted that new nurses are continually striving to acquire the nursing skills they lack and to improve their work performance [17]. However, in Korea, the formal training period averaging less than 2 months is notably shorter than in many other countries, where training typically extends beyond 6 months [35, 37]. This discrepancy indicates a potential gap in the breadth and depth of training provided to Korean nurses, possibly impacting their readiness and confidence in performing complex clinical tasks. To address these challenges, it is essential to leverage existing dedicated nurse training programs in Korea. These programs should focus on spreading shared knowledge through structured and step-by-step practical training. Implementing team education programs and offering ongoing learning opportunities are crucial strategies that can help bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. These methods ensure that new nurses not only learn specific skills but also understand the context and rationale of their actions, which is essential for holistic patient care.

Seven to twelve months into their hospital roles, new nurses face a critical phase marked by increasingly complex challenges, compounded by the pressure to enhance performance efficiency. A report indicates that it can take between eight and twelve months for new nurses to adjust to the realities of their roles and to become fully operational [38]. In Korea, nurses frequently encounter considerable workloads before they have had sufficient time to become proficient in their duties [38]. New nurses experience significant pressure as they attempt to manage a demanding workload, adapt to the complexity of their role, and meet higher expectations, which can ultimately lead to burnout [34]. This often leads them to engage in repetitive checks to minimize errors as a coping strategy to address their concerns about falling behind in their learning and skill acquisition [39, 40]. In order to solve this problem, continuous support must be provided to increase confidence in work and performance ability by continuing practical training through a nurse in charge of education for up to 12 months to strengthen competency. Moreover, the development of self-regulated internal management programs to reduce workload and burden is essential, alongside organizational-level management efforts to support new nurses’ integration into the healthcare environment as competent professionals. New nurses still complained of difficulties in handover. Handover is one of the important tasks of a nurse as it saves time in checking and understanding the patient’s key information [41]. However, for new nurses, omission of important information during handover, questions from peer or senior nurses, or lack of preparation due to busy ward environment can result in work burden and frustration [41]. A standardized handover process is necessary to systematically and accurately convey information, and a simulation process needs to be included for realistic practice.

Nevertheless, this study has a few limitations. This study analyzed reflective journals from new nurses at a single university hospital, necessitating caution in generalizing the results. The free text format may influence the interpretation of words and expressions, and the lack of data analysis specific to departmental characteristics necessitates careful interpretation of the data. Despite these limitations, our findings underscore the need for a dynamic, integrative approach in nursing education that harmonizes theoretical knowledge with practical skills. To facilitate this, nursing curricula should be restructured to include simulation-based training and real-world clinical scenarios, fostering a seamless transition from classroom learning to clinical application. Notably, healthcare organizations play a pivotal role in this adaptive process. Establishing a nurturing work environment, replete with resources for continuous learning and professional development, can significantly reduce job stress and enhance job satisfaction among new nurses. Future research should explore the long-term impact of such integrative educational and organizational strategies on the professional development and psychological well-being of new nurses. Additionally, future studies should conduct group-specific analyses to examine the characteristics of various departments, such as intensive care units, general wards, and operating rooms.

CONCLUSION

This study crucially identifies the evolving challenges faced by new nurses during their first year in a hospital setting. It highlights the need for educational reforms that bridge the gap between academic theory and clinical practice and the importance of creating a supportive work environment. The distinct phases of adaptation—from grappling with basic clinical skills to managing complex patient care and emotional labor—call for targeted support strategies to enhance resilience and competence; specifically, such strategies may include structured mentoring, practical training, and emotional support mechanisms. Further, our findings clarify the need to implement an integrated approach in nursing education and organizational support designed to improve the overall well-being and professional development of new nurses. The insights from this study contribute to the broader discourse on effective strategies for nurse induction and retention and have implications for healthcare quality and patient care.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:The authors declared no conflict of interest.

FUNDING:This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea fund in Korea (No. NRF-2022R1F1A1067574).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: Ahn S & Jeong H & Yang S & Jung U & Choi M & Kim H.

Data curation or/and Analysis: Ahn S & Jeong H & Yang S & Jung U & Choi M & Kim H.

Funding acquisition: Jeong H.

Investigation: Ahn S & Jeong H & Yang S & Jung U & Choi M & Kim H.

Project administration or/and Supervision: Choi M & Kim H.

Resources or/and Software: Ahn S & Jeong H.

Validation: Choi M & Kim H.

Visualization: Jeong H.

Writing original draft or/and Review & Editing: Ahn S & Jeong H & Yang S & Jung U & Choi M & Kim H.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

References

-

Hospital Nurses Association. 2022 annual report: Hospital nurse staffing status survey [Internet]. Hospital Nurses Association; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 24].Available from: https://khna.or.kr/home/pds/utilities.php?bo_

table=board1&wr_ id=8115.

-

-

Mounayar J, Cox M. Nurse practitioner post-graduate residency program: Best practice. Journal for Nurse Practitioners 2021;17(4):453–457. [doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.10.023]

-

-

Park JH, Lee MH. Effects of a practical work-oriented education program on the ability of newly recruited nurses in execution of clinical competency, critical thinking and turnover rate. Journal of Digital Convergence 2017;15(7):191–199. [doi: 10.14400/JDC.2017.15.7.191]

-

-

Kwon IG, Cho YA, Cho MS, Yi YH, Kim MS, Kim KS, et al. New graduate nurses’ satisfaction with transition programs and experiences in role transition. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research 2019;25(3):237–250. [doi: 10.22650/JKCNR.2019.25.3.237]

-

-

Lee I, Shin S, Kim J, Hong E. Outcomes of a government support project for clinical nurse educator and policy recommendations: From the perspectives of clinical nurse educators. Health & Nursing 2023;35(2):39–47. [doi: 10.29402/HN35.2.5]

-

-

Lee OS, Kim MJ. The relationship between emotional intelligence, critical thinking disposition and clinical competence in new graduate nurses immediately after graduation. Journal of Digital Convergence 2018;16(6):307–315. [doi: 10.14400/JDC.2018.16.6.307]

-

-

Hwang H, Lee Y. Newly graduated nurse’s resilience experience. Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2021;21(10):656–667. [doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2021.21.10.656]

-

-

Na HJ, Yoo SH, Kweon YR. Resilience mediates the association between job stress and turnover intention of among new graduate nurses. Journal of the Korean Data Analysis Society 2022;24(1):133–147. [doi: 10.37727/jkdas.2022.24.1.133]

-

-

Kim S, Hyun MS. A study of intention to stay, reality shock, and resilience among new graduate nurse. Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2022;22(10):320–329. [doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2022.22.10.320]

-

-

Lee DH. A study on psuedonymized and de-identified information for the protection and free movement of personal information. Journal of Korea Information Law 2017;21(3):217–251.

-

-

Cyram. NetMiner [Computer Program]. Version 4.4. Seongnam: Cyram Inc; 2018Available from: https://www.netminer.com/kr/.

-

-

Park CS. Simulation nursing education research topics trends using text network analysis. Journal of East-West Nursing Research 2020;26(2):118–129. [doi: 10.14370/jewnr.2020.26.2.118]

-

-

Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks 1978-1979;1(3):215–239. [doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7]

-

-

Clauset A, Newman ME, Moore C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Physical Review. E, Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2004;70(6 Pt 2):66111 [doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111]

-

-

Moon KJ, Cho MY. Factors influencing the transition shock of newly-graduated nurses. Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education 2022;28(2):156–166. [doi: 10.5977/jkasne.2022.28.2.156]

-

-

Shin S, Park YW, Kim M, Kim J, Lee I. Survey on the education system for new graduate nurses in hospitals: Focusing on the preceptorship. Korean Medical Education Review 2019;21(2):112–122. [doi: 10.17496/kmer.2019.21.2.112]

-

-

Jeong H, Moon SH, Ju D, Seon SH, Kang N. Effects of the clinical core competency empowerment program for new graduate nurses led by clinical nurse educator. Crisisonomy 2021;17(6):109–123. [doi: 10.14251/crisisonomy.2021.17.6.109]

-

-

Shin S, Kim SH. Experience of novice nurses participating in critical reflection program. Journal of Qualitative Research 2019;20(1):60–67. [doi: 10.22284/qr.2019.20.1.60]

-

-

Ju EA, Park MH, Kim IH, Back JS, Ban JY. Changes in positive psychological capital, organizational commitment and burnout for newly graduated nurses. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research 2020;26(3):327–336. [doi: 10.22650/JKCNR.2020.26.3.327]

-

-

Yoo MS, Jeong MR, Kim KJ, Lee YJ. Factors influencing differences in turnover intention according to work periods for newly graduated nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 2019;25(5):489–498. [doi: 10.11111/jkana.2019.25.5.489]

-

-

Yun HJ, Kwak EM, Kim HS. Focus group study on reality shock experiences of new graduate nurses. Journal of Qualitative Research 2018;19(2):102–111. [doi: 10.22284/qr.2018.19.2.102]

-

-

Kim S, Shin S, Lee I. Exploring the roles and outcomes of nurse educators in hospitals: A scoping review. Korean Medical Education Review 2023;25(1):55–67. [doi: 10.17496/kmer.22.026]

-

-

Kim SH, Kim JS. Predictors of emotional labor, interpersonal relationship, turnover intention and self-efficacy on job stress in new nurses. Journal of Digital Convergence 2020;18(11):547–558. [doi: 10.14400/JDC.2020.18.11.547]

-

-

Ji EA, Kim JS. Factor influencing new graduate nurses’ turnover intention according to length of service. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 2018;24(1):51–60. [doi: 10.11111/jkana.2018.24.1.51]

-

-

Choi JH, Lee SO, Kim SS. The effects of empathy and perceived preceptor’s empathy on job satisfaction, job stress and turnover intention of new graduate nurses. Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2019;19(3):313–327. [doi: 10.5392/JKCA.2019.19.03.313]

-

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite