Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 48(3); 2018 > Article

- Original Article Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale–Short-Form in Cancer Patients

- Chi Eun Song1, Hye Young Kim2, Hyang Sook So3, Hyun Kyung Kim2,

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2018;48(3):375-388.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.3.375

Published online: January 15, 2018

2College of Nursing · Research Institute of Nursing Science, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju

3College of Nursing, Chonnam National University · Chonnam Research Institute of Nursing Science, Gwangju,

-

Corresponding author:

Hyun Kyung Kim,

Email: tcellkim@jbnu.ac.kr

Abstract

This study was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale-Short-Form in patients with cancer.

The original scale was translated into Korean using Brislin's translation model. The Korean Short-Form and the Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy-General were administered to 164 Korean patients with cancer using convenience sampling method. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 23.0. Construct validity, criterion validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency reliability of the Korean Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale-Short-Form were evaluated.

Exploratory factor analysis supported the construct validity with a four-factor solution that explained 60.6% of the total variance. Factor loadings of the 15 items on the four subscales ranged .52~.86. The four-subscale model was validated by confirmatory factor analysis (Normed χ 2=1.38 (

The Korean version showed satisfactory construct and criterion validity, as well as internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

Published online Jun 30, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.3.375

Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale–Short-Form in Cancer Patients

Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale-Short-Form in patients with cancer.

Methods

The original scale was translated into Korean using Brislin's translation model. The Korean Short-Form and the Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy-General were administered to 164 Korean patients with cancer using convenience sampling method. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 23.0. Construct validity, criterion validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency reliability of the Korean Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale-Short-Form were evaluated.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis supported the construct validity with a four-factor solution that explained 60.6% of the total variance. Factor loadings of the 15 items on the four subscales ranged .52~.86. The four-subscale model was validated by confirmatory factor analysis (Normed χ2=1.38 (p=.013), GFI=.92, SRMR=.02, RMSEA=.05, TLI=.94, and CFI=.95), and criterion validity was demonstrated with the Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy-General. Cronbach's alpha for internal consistency of the total scale was .83 and ranged .68~.81 for all subscales, demonstrating sufficient test-retest reliability.

Conclusion

The Korean version showed satisfactory construct and criterion validity, as well as internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

INTRODUCTION

Research on coping in relation to individual health has a long history. In general, coping is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that claim or exceed an individual's resources [1]. It is recognized as the crucial variable in understanding the effect of stress on physical and mental health [2, 3]. In other words, in crises or extremely difficult situations involving stress, coping is the most relevant mediator in the stress-outcome relationship.

Idiosyncratic individual and family coping with the demands of illness such as cancer influences adjustment and well-being throughout one's lifetime. Therefore, patients with cancer and their families have to develop coping strategies to modify the lifestyles disrupted by illness and additional physical demands, and to overcome the psychosocial burdens associated with illness [4]. Patients with cancer can mediate the psychosocial effects of their illness by determining effective coping strategies [5]. Thus, oncologists need to assess cancer patients' coping strategies to improve their adjustment to the treatment process.

Recently, coping research has emerged as a core aspect of stimuli adaptation in altered lifestyles resulting from illness. This is due to theoretical evidence that suggests that different coping strategies can lead to an individual's adaptation or maladaptation [1, 6], and that coping influences the individual's psychological and physical well-being [7, 8]. Consequently, several instruments for measuring coping behaviors have been developed and research has examined factors of coping. However, in Garcia's review [9] on conceptualizing and measuring coping, empirical weakness in coping assessment significantly challenged and limited the applicability and relevance of coping data [10]. In addition, gaps exist between the acknowledged need to identify individual coping strategies and subtypes of coping behaviors and measures that can distinguish between these subtypes [9]. In particular, nursing research has relied on Lazarus and colleagues' research [2, 11]. The Ways of Coping Checklist developed by Lazarus & Folkman [1] –a widely used instrument–went through several revisions and was subsequently revised into the Ways of Coping Questionnaire, by modifying scale items and response format. Although Lazarus has been considered the standard in the field, a number of authors noted that the construct validity of the instrument was not strong, given its unstable factor structure [2, 11]. Nurse researchers found that they lost discrimination in measurement by relying on the distinction between problem-solving and emotional coping, as it does not explore the rich cognitive and behavioral domains of coping [11, 12].

This led to the development of an alternative conceptualization and measurement tool. Roy's Middle-Range Theory (MRT) considers that the “cognator,” a subsystem of the coping process, reacts to stimuli as a multidimensional and transactional process; MRT holds that coping and adaptation occur through four adaptive modes and three information-processing types: input, central, and output [3, 6]. Roy [3] also devised the 47-item Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale (CAPS), a self-report measure to assess the coping adaptation process of individuals in stressful situations. This scale has been used by numerous investigators in several countries and has been translated into six languages [11]. The 47-item CAPS was subsequently shortened to the 15-item version using item analysis based on item response theory (IRT) to meet the demands of various clinical settings and to measure the coping behaviors of patients experiencing short-term events and those with chronic health conditions [11]. The original 15-item CAPS-Short-Form (SF) had satisfactory Cronbach's alpha coefficients, and preliminary validity (i.e., face, concurrent, and divergent validity) was confirmed [11].

Cancer presents a wide range of situations with which to cope, such as painful or frightening symptoms, psychological distress, ambiguity about disease prognosis, and changes in social relationships [4, 7, 8, 13]. Thus, cancer patients can use coping strategies to help them adjust in physical, emotional, role-related, and interpersonal domains. The coping strategies in Roy's MRT were defined as “behaviors whereby adaptation processing is carried out in daily situations and in critical periods; categories synthesized from behaviors in four adaptive modes, physiologic, self-concept, role function, and interdependence” [3, 6]. The 15-item CAPS-SF is also based on Roy's MRT and includes coping strategies in four adaptive modes, three information-processing types, and spirituality. During the course of treatment, patients with cancer can experience various crises or extremely difficult events at acute and chronic stages [13]. The CAPS-SF is a 15-item questionnaire that can be used to assess rapid coping strategies for patients in illness conditions. Therefore, the 15-item CAPS-SF is a useful instrument for providing an overall understanding of coping behaviors a cancer patient adopts in stressful situations.

Accordingly, the purpose of the present study was to translate the 15-item CAPS-SF developed by Roy et al. [11] so that it reflects and can be applied, to the conditions of Korea and to test its reliability and validity such that the Korean version CAPS-SF (KCAPS-SF) can be used in research involving the assessment of Korean cancer patients' coping strategies.

METHODS

1. Study design

The present study used methodological research to translate the CAPS-SF developed by Roy et al. [11] into Korean and to test the validity and reliability of KCAPS-SF.

2. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of C National University H Hospital (IRB No. CNUHH-2015-053). The study is in accordance with accepted national and international standards of ethics.

3. Participants

Participants in this study were patients with cancer undergoing inpatient care in the hematology-oncology ward or attending the outpatient clinic of the C National University H Hospital located in J province. All participants were at least 19 years old, had no communication issues due to cognitive impairment, and agreed to participate in the study. The pilot study sample comprised 40 patients (Sample 1), while 164 patients with cancer participated in the main investigation of validity and reliability (Sample 2).

The recommended number of data points appropriate for exploratory factor analysis (EFA)–to assess construct validity–is five times the number of scale items (10 times the number of items is ideal) [14]. The most common method of estimation in structural equation modeling (SEM) for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), in which a sample size of 100~400 is considered adequate and 200 considered most appropriate [14]. Our main investigation included 180 participants, and data from 164 (91.1%) participants were used for analysis after excluding missing data from 16 participants. Since there are 15 items in the CAPS-SF, a total of 164 participants is the ideal sample size according to the EFA standard, which is also adequate for CFA and MLE standards.

Data was collected from May to December in 2015. The questionnaire was distributed in person by the researcher. Participants were given sufficient explanations regarding the necessity and purpose of the study, benefits of participation, right to withdraw, guarantee of anonymity and confidentiality, instructions for completing the questionnaire, and time required. Data collection began upon obtaining voluntary written consent to participate in the study. The questionnaire took 15 minutes to complete. The completed questionnaires from the pilot and main studies were placed in sealed envelopes and collected in person by the researcher. In addition, to assess test-retest reliability, a convenience sample comprising 30 of the 164 total patients was asked to complete the KCAPS-SF two weeks after the main investigation was conducted.

4. Instruments

1) Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale-Short-Form (CAPS-SF)

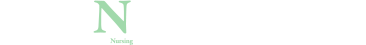

The CAPS, based on Roy's adaptation theory [3], is a self-report measure developed to assess the coping adaptation process of individuals in stressful situations. Each item is a short statement about how an individual responds to a crisis or extremely difficult event. The original questionnaire had 47 items with 5 sub-factors: resourceful and focused, physical and fixed, alert processing, systematic processing, and knowing and relating. The meaning of each sub-factor is as follows. Resourceful and focused is a major dimension of the construct of coping and adaptation processing that reflects behaviors using self and resources. It concentrates on expanding input, being inventive, and seeking outcomes. Physical and fixed is the dimension that highlights physical reactions and the input phase of handling situations. Alert processing is the dimension of coping and adaptation that uses behaviors that represent both the personal and physical self. It focuses on all three levels of processing: input, central, and output. Systematic processing describes personal and physical strategies used to take in situations and methodically handle them as a dimension of coping. Finally, knowing and relating is the dimension in which the strategies reflect the use of self and others, memory, and imagination. Cronbach's α coefficient for 47 items was .94 during the development, while Spearman-Brown split-half reliability scores for the five subscales were: .84 for resourceful and focused, .84 for physical and fixed, .80 for alert processing, .74 for systematic processing, and .78 for knowing and relating [3]. The 47-item CAPS was shortened to the 15-item version by Roy et al. [11] through item analysis based on IRT. The original 15-item CAPS-SF had satisfactory Cronbach's alpha coefficients (.82), and the preliminary validity of the 15-item CAPS-SF was confirmed. Face validity was confirmed in that items of the CAPS-SF are based on the MRT of coping and adaptation processing (i.e., including all adaptive modes and all types of cognitive processes). Concurrent validity was examined in an intervention study of 50 participants with spinal cord injuries. The scores on the CAPS-SF correlated with a value of .38 with Quality of Life (QoL) measure [11]. In addition, divergent validity was demonstrated in a correlational study of a sample of 35 patients with other neurologic disabilities. The CAPS-SF has a negative correlation of −.39 with self-reports of cognitive deficits, specifically concentration and memory difficulties [11]. The CAPS-SF uses a Likert scale format with response choices ranging from 4 (always) to 1 (never). Three items are reverse scored (items 5, 13, and 14). The possible range of scores is 15~60, with a high score indicating a greater capacity for using effective coping strategies [11].

2) Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G)

To assess criterion validity, the Korean version of the FACT-G (version 4), developed by Cella et al. [15] and validated for Korean patients with cancer by Kim et al. [16], was used after obtaining permission through the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Measurement System. The FACT-G is a measure that has globally established validity and reliability. This self-report scale measures both functional aspects and multidimensional domains of QoL such as physical, social/family, and emotional aspects that patients with cancer can experience in their course of treatment. Based on previous research suggesting that the use of effective coping strategies positively influences QoL [7, 8, 11, 17], we c onsider Q oL a n appropriate c oncept for evaluating the CAPS-SF's criterion validity.

This tool comprises 25 items on the QoL of patients with cancer, classified into 4 sub-factors: six physical well-being items, six social/family well-being items, six emotional well-being items, and seven functional well-being items, scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “absolutely no” to 4 “always.” The total range of scores is 0~100 points, where a higher score means better QoL. Cronbach's α when developing the Korean version was .90 [16]. Cronbach's α in the present study is .91 for the overall questionnaire, .89 for physical well-being, .87 for social/family well-being, .88 for emotional well-being, and .89 for functional well-being sub-factors.

3) Participants' general and clinical characteristics

Seven items were used to assess gender, age, marital status, education level, occupation, type of diagnosis, and duration of disease.

5. Translation and cultural adaptation processes

1) Translation and back translation process

Permission to translate and use the CAPS-SF was obtained via email correspondence with its developer, Roy. The translation and cultural adaptation process was based on Brislin's translation model [18, 19] and Roy and Chayaput's translation and cultural adaptation process [20]. Forward translation was conducted first, followed by the first panel discussion, back translation, a second panel discussion, a review of the back translation by the developer of the instrument, a content validity test, a pilot test, and final completion.

Forward translation of the measure from English to Korean was performed by two nursing professors proficient in both Korean and English. The first panel discussion was conducted to review translation accuracy, sentence structure, and similarity or congruence of meaning between the original, forward-, and translated items. This expert panel comprised the first two translators, an expert in English literature with a doctorate, two nursing professors with experience in scale development, and an oncology nurse. The translated scale was back translated into English by two bilingual English literature professors. Mutual independence was maintained between forward and back translators. The second panel discussion was conducted to review simplicity of terminology and similarity or congruence of meaning between original, forward-, and back-translated items. This expert panel comprised the two forward translators and back translators, an expert in English literature with a doctorate, two nursing professors with experience in scale development, and an oncology nurse. Only basic revisions were made such as switching the order of phrases in the 15 items. The translated CAPS-SF retained the same scale format, sequence, and item numbers as the original measure, and was confirmed by Roy, its developer.

2) Content validity

To test the content validity of the translated CAPS-SF items after the forward and back translation, a group of eight oncology nursing experts was formed: three adult nursing professors, one nursing professor in charge of the university's cancer nursing department, two nursing professors with experience in scale development, one oncologist, and one oncology nurse. They rated each preliminary scale item using a 4-point Likert scale: 1 “very inadequate,” 2 “inadequate,” 3 “adequate,” and 4 “very adequate.” The Content Validity Index (CVI) was computed as the proportion of experts rating an item as 3 or 4 [21]. The resulting itemlevel CVI was .80 or higher for each item; therefore, all 15 items were included in the final questionnaire.

3) Pilot test

Prior to the main investigation, a pilot test of the translated CAPS-SF was conducted to confirm that the scale's word difficulty level, sentence comprehension, and organization were appropriate, and that there were no difficulties associated with responding. The pilot test was conducted April 13~17, 2015. Participants were 30 patients with cancer visiting the hematology-oncology outpatient clinic of the C National University H Hospital. The questionnaire took eight minutes to complete. The results of the pilot test showed that eight participants (26.7%) found the meaning of Item 13, “Tend to become ill,” difficult to understand, while 14 participants (46.7%) responded that it was confusing, which prompted sentence revision. For Item 8, “Am more effective under stress,” five participants (16.7%) found the meaning of the sentence difficult, five (16.7%) found the meaning confusing, and six participants (20.0%) reported being disconcerted when responding, which also called for sentence revision. Therefore, after expert panel discussion, Item 13 was revised as “Tend to lie sick in bed” and Item 8 as “Can solve problems more effectively under stress.” The second pilot test was conducted on April 20, 2015 with 10 cancer patients using the preliminary scale with revised items (Items 8 and 13). The results of the pilot test showed agreement that there were no difficulties in understanding and responding to all items in the questionnaire. Cronbach's α was .85 for all items in the second pilot test.

6. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and appropriate reliability and validity statistical tests were performed with SPSS version 23.0 and AMOS 23.0. Descriptive statistics were used to determine frequency, range, mean, and standard deviation of the sample's demographic and clinical characteristics. All other tests were two-tailed, and a p value of less than 5% was considered statistically significant.

Item analysis included the mean and standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis, ceiling and floor effect, and corrected item-total correlation coefficients. For construct validity, EFA and CFA were performed. We used principal component factor analysis as the factor extract model to minimize information loss from minimum-factor prediction and varimax rotation to clearly classify factors by maximizing the sum of factor-loading variance [22]. First, we performed the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett Sphericity to confirm the appropriateness of materials collected prior to the factor analysis [22]. For extracting the factors through EFA, the number of factors was determined by the following criteria: eigenvalue of 1 or above, factor loading of .50 or above, and accumulative variance of 60.0% or above [14]. For the CFA model verification comprising sub-factors categorized through EFA, the goodness of fit coefficients, Normed χ2 (χ2/df), goodness of fit index (GFI), standardized root mean residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI) were verified. In addition, to achieve convergent validity among sub-factors, factor loading, average variance extracted (AVE), and construct reliability (CR) were examined; further, to achieve discriminant validity, we confirmed that each sub-factor's AVE was greater than the sum of squares of the correlation coefficients between sub-factors. For criterion validity, Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated for KCAPS-SF and FACT-G. Reliability of the KCAPS-SF was analyzed using Cronbach's alpha coefficients, and test-retest reliability was analyzed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between the first and second administration of all items.

RESULTS

1. Participants' characteristics

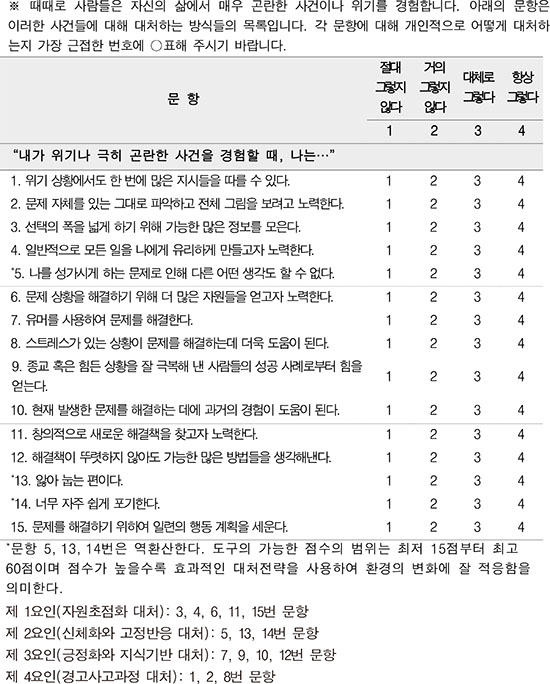

Participants' general and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Mean age was 46.64 years (standard deviation [SD]=13.29), and 59.1% (n=97) were male. In addition, 40.9% (n=67) had attained at least college-level education and 55.5% (n=91) of the participants were employed. A total of 69.5% (n=114) of the participants had acute leukemia, while 36.6% (n=60) of participants' disease duration was at most five months, and mean disease duration was 29.48 months (SD=104.82).

Table 1

General and Clinical Participant Characteristics (N=164)

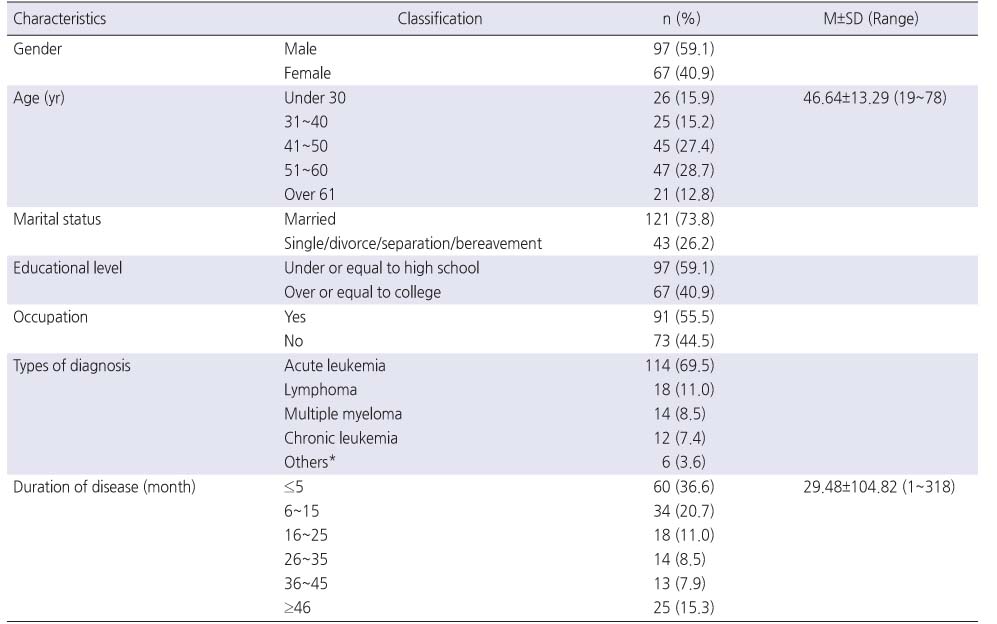

2. Item analysis of the KCAPS-SF

Item analysis of the KCAPS-SF revealed that the mean item score ranged 2.38~3.11, and the SD ranged 0.56~0.71. The total KCAPS-SF score was 42.03±5.14. The rate of missing values was 0.0% for all items. Skewness and kurtosis in absolute values for each item ranged 0.01~1.02 and 0.09~0.91, respectively. Since both skewness and kurtosis were distributed within the absolute value±1 range, they were not far off from the assumption of normal distribution. The ceiling effect for each item ranged 6.1~14.6%, and the floor effect ranged 0~3.0%, both under the acceptable standard of less than 15.0% for all items [23]. In addition, the ceiling effect for each sub-factor ranged 2.4~5.5%, and the floor effect ranged 0.6~1.2%. Corrected item-total correlation showed a minimum of .40 (Item 8) and maximum of .72 (Item 14), exceeding the standard value (≥.40) [24] for all items (Table 2).

Table 2

Items and Subscales Characteristics and Reliability of KCAPS-SF (N=30)

3. Construct validity

1) Factor analysis

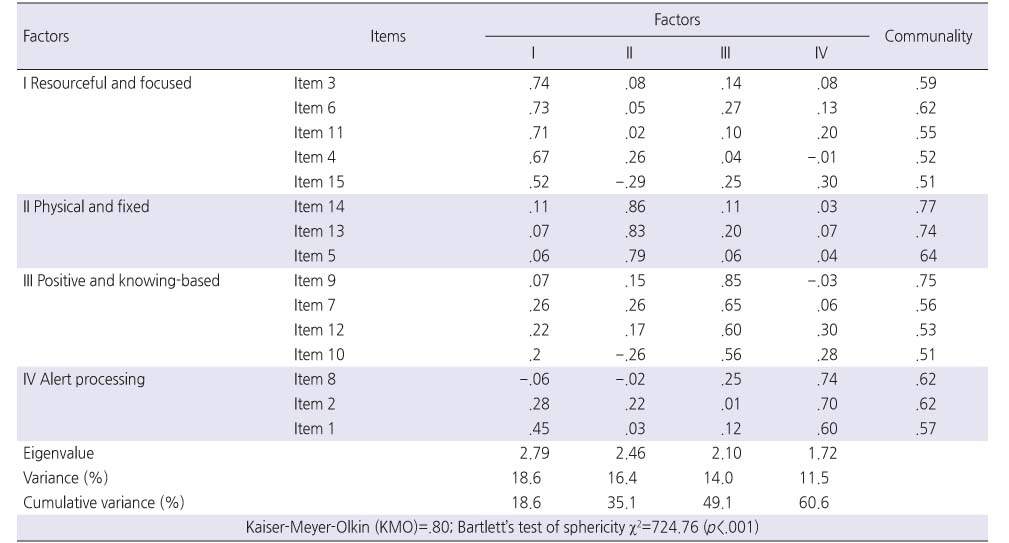

Previous studies have not performed factor analysis of the 15- item CAPS-SF and could not confirm the factor structure. Therefore, EFA was performed to confirm the factors and structure of the use of the instrument with cancer patients. The KMO to determine whether the 15 items used in the present study were adequate for EFA was .80, which exceeds the standard value of .60 [14]. Bartlett Sphericity verifies the null hypothesis–the correlation matrix of the variables is an identity matrix–which implies adequacy for factor analysis [22]; Bartlett Sphericity was χ2=724.76 (p<.001), which is adequate for factor analysis. EFA was performed using varimax rotation, an orthogonal rotation method in principal component factor analysis.

First, the 15-item CAPS-SF was reported on a unidimensional scale at the time of development, without performing the factor analysis. Therefore, in this study, EFA was performed setting the factor number to 1. However, the factor loadings for the 15 items ranged from .39 (Item 8) to .67 (Item 6), not satisfying the criterion of .50 or above in 5, 8, 10, 14, and 15 items. In addition, the explanatory power of total variance was 29.9%, which did not meet the standard value of 60.0%.

Therefore, we performed the rotation again based on the scree plot and eigenvalue of 1 and above for the factor extraction. As a result, four factors with an eigenvalue of 1.0 or above were extracted, which explained 60.6% of the total variance. The factor loadings for the 15 items ranged from .52 (Item 15) to .86 (Item 14), satisfying the criterion of .50 or above in all items [14] (Table 3).

Table 3

Factor Loading from Exploratory Factor Analysis for KCAPS-SF in Four Sub-factors Model

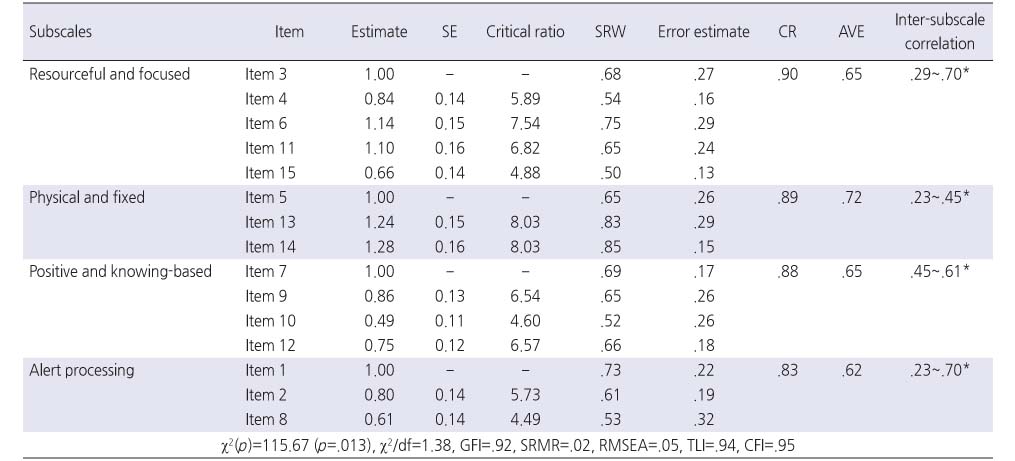

CFA was performed on the four sub-factors extracted in the EFA. T he standardized regression weight for e ach item w as .50~.85, exceeding the criterion of .50 [22] for all items. Results of the goodness of fit tests for the 15 items and four sub-factors of the KCAPS-SF were χ2 (p)=115.67 (.013), Normed χ2=1.38, GFI=.92, SRMR=.02, RMSEA=.05, TLI=.94, and CFI=.95 (Table 4). That is, Normed χ2 was below 3 [14]; GFI, TLI, and CFI above .90 [14, 22]; and SRMR and RMSEA below .05 [14, 22], indicating good model fit (Table 4).

Table 4

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for KCAPS-SF

Convergent validity assesses consistency in measuring a construct across items in the scale. In this study, since the critical ratio was 4.49~8.03 (p<.001), satisfying the criterion of ≥1.96 [22]; AVE was .62~.72, satisfying the criterion of ≥.50 [22]; and CR was .83~.90, satisfying the ≥.70 criterion [22], convergent validity was confirmed for the 15-item KCAPS-SF (Table 4). Discriminant validity of items is the degree to which sub-factors differ from each other. Items demonstrate discriminant validity of the AVE of a sub-factor is greater than the squared correlation coefficient between sub-factors [22]. Correlation coefficients between sub-factors ranged .23~.70, and since the squared value of the greatest coefficient, (.70), was .49, the AVE of each sub-factor (range .62~.72) was confirmed to be greater. Therefore, the low correlation between sub-factors of the scale indicates that independence is maintained between the sub-factors and discriminant validity was achieved (Table 4).

2) Factor naming

Factors were named according to the meaning of high-factor loading items in each sub-factor and by referencing the factor names of each sub-factor in the original 47-item CAPS [3]. The first factor included five items such as “Gather as much information as possible to increase my options” and “Try to get more resources to deal with the situation” and was named “Resourceful and focused coping” because it reflects an individual coping strategy of systematically gathering resources and information in order to understand and solve a problem. The eigenvalue of “Resourceful and focused coping” was 2.79 with 18.6% of its variance explained, and factor loadings of items ranged .52~.74. The second factor included three items such as “Give up easily too often” and “Tend to lie sick in bed” and was named “Physical and fixed coping” because it reflects the initial stages of coping involving the management of physical responses and stress. Its eigenvalue was 2.46 with 16.4% variance explained, and factor loadings of items ranged .79~.86. The third factor included four items such as “Take strength from spirituality or the successes of courageous people” and “Use humor in handling the situation,” and was named “Positive and knowing-based coping” because it reflects the attempt to solve a problematic situation by gathering relevant knowledge for effective coping, including one's own or others' successful experiences, the use of humor, and generating as many solutions as possible. The eigenvalue of “Positive and knowing-based coping” was 2.10 with 14.0% of variance explained, and item factor loadings ranged .56~.85. The fourth factor included three items such as “Can solve problems more effectively under stress” and “Call the problem what it is and try to see the whole picture” and was named “Alert processing coping” because it reflects alert, careful, and thoughtful coping and analysis of a problem. Its eigenvalue was 1.72 with 11.5% variance explained, and item factor loadings ranged .60~.74 (Table 3). The procedures of factor naming of the sub-factors in the KCAPS-SF and the names of each sub-factor were sent to Roy, the instrument's developer through an email and the results were confirmed by Roy.

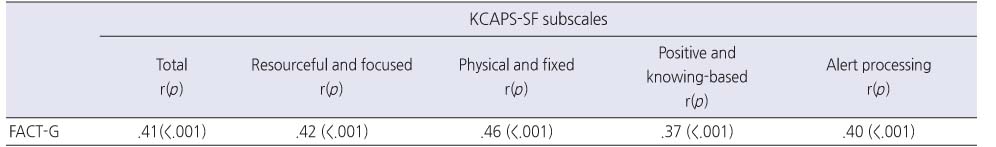

4. Criterion validity

The KCAPS-SF's criterion validity was tested by correlating it with QoL, since previous research has yielded positive correlations [4, 7, 8, 17]. A statistically significant positive correlation was observed between the KCAPS-SF and FACT-G (r=.41, p<.001; Table 5).

Table 5

Correlations between the Subscales in KCAPS-SF and FACT-G for Criterion Validity

5. Score distributions of sub-factors and reliability assessment

The KCAPS-SF scores for sub-factors were 15.03±2.19 for resourceful and focused coping, 7.31±1.78 for physical and fixed coping, 11.28±1.81 for positive and knowing-based coping, 8.41±1.37 for alert processing coping, and 42.03±5.14 for the overall scale (Table 2). The reliability assessment (Cronbach's α) of the final 15-item scale was .83 for all items and ranged .68~.81 across sub-factors. Test-retest reliability (ICC) that assesses the stability of the scale was r=.83 for all items and ranged .81~.85 across sub-factors (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The CAPS-SF is an instrument that measures the coping strategies of individuals experiencing short-term events and those with chronic health conditions. During the course of treatment, patients with cancer can experience various crises or extremely difficult events at acute and chronic stages. The present study provides initial evidence for the KCAPS-SF's content validity, construct validity, criterion validity, and reliability for use with cancer patients. Four factors were extracted: resourceful and focused, physical and fixed, positive and knowing-based, and alert processing coping (Appendix 1).

The reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) of the original version of the CAPS was .94 for the 47-item instrument and ranged .74~.84 for its five sub-scales [3]. In publications in four countries (US, Thailand, Colombia, and Turkey), the Cronbach's α coefficient for the total CAPS were reported as ranging from .81 to .94, and the subscales ranged from .65 to .96, with one outlier described at .31 (systematic processing subscale) [11]. Cronbach's α of the 15-item CAPS-SF was .82 [11]. In this study, Cronbach's α was .83 for the overall instrument and ranged .68~.81 for subscales. Nunnally & Bernstein [25] indicated that newly developed measures can be accepted with a Cronbach's α value of .60; otherwise, .70 should be the threshold. However, considering the use of these scales for the first time within a new culture, the cutoff value for the Cronbach's α coefficient was set to .60 for all the scales [25]. The current study is the first to verify the test-retest reliability of the CAPS-SF, indicating “good” reliability because ICCs exceeded the .80 criterion [25]. Thus, the relatively high alpha coefficients and ICCs demonstrated strong reliability.

This study was the first to perform the factor analysis of the 15-item CAPS-SF, which only performed preliminary validity (face validity, concurrent validity, and divergent validity) when items were reduced from the 47-item CAPS [11]. That is, although the CAPS-SF was shortened to 15 items through IRT, the factor structure was unknown, since EFA and CFA were not performed. To date, CAPS has been shortened to measure coping strategies easily [26, 27]. In Zhan's study [26], CAPS was extracted with five sub-factors: clear focus and methods, knowing awareness, self-perception, sensory regulation, and selective focus, and total explanatory variance was 48.0%. In Chayaput & Roy's study [27], the 27-item Thai version of the CAPS-SF demonstrated four sub-factors with 51.6% of total explained variance: resourceful and focused, physical and fixed, positive and knowing, and alert processing, namely. Thus, coping strategies were identified as multidimensional concepts because they were not extracted as one factor in both studies [26, 27]. Meanwhile, the 15-item CAPS-SF was considered to be a unidimensional scale at the time of development [11], but the factor structure of the tools could not be confirmed. In other words, it is unclear whether the factor structure of 15-item CAPS-SF has unidimensionality or multidimensionality. For the first time in this study, EFA was performed to verify the construct validity of the 15-item CAPS-SF. Under IRT, the factor analysis should ideally result in a one-factor solution. Therefore, in this study, EFA was performed setting the factor number to 1. However, factor loadings and explanatory power of total variance did not meet the standard value. Therefore, we performed the rotation again based on the scree plot and eigenvalue of 1and above for the factor extraction. As a result, EFA of the 15-item KCAPS-SF in the present study extracted four factors, including resourceful and focused coping, physical and fixed coping, positive and knowing-based coping, and alert processing coping, and factor loadings and total explanatory variance were above the standard value. As yet, no studies have verified the construct validity of the 15-item CAPS-SF. Thus, future studies should re-examine its factor structure.

The content [27, 28], construct [10, 27], and criterion validity [26] of the CAPS was supported by the researchers in a number of ways. For example, Alkrisat & Dee [10] conducted a CFA to support construct validity of the 47-item CAPS using subjects of nurses working in acute health care facilities, which demonstrated good fit. The original 15-item CAPS-SF had also satisfactory face validity, concurrent validity, and divergent validity [11].

In this study, construct (convergent and discriminant validity for four subscales) and criterion validity were used to test validity. Normed χ2, GFI, SRMR, RMSEA, TLI, and CFI indicated good fit, and the measurement model of 15 items and four subscales was accepted. The CFA results showed that AVE values for resourceful and focused, physical and fixed, positive and knowing-based, and alert processing coping subscales exceeded .50, and the CR values for the four subscales exceeded .70. Therefore, the results confirmed convergent validity for each subscale. In addition, AVE values for the subscales were higher, relative to r2 values; therefore, discriminant validity for each subscale was confirmed.

In order to verify the criterion validity, this study utilized the FACT-G questionnaire to assess cancer-related QoL variables. In this study, significant correlations were found between the 15-item KCAPS-SF and subscales of the FACT-G. The range of correlation coefficients for the FACT-G and 15-item CAPS-SF was .41, which was satisfactory according to the recommended range for correlation coefficients (r=.40 to r=.80) [29] to establish concurrent validity. Thus, the criterion validity of the 15-item CAPS-SF was established.

Therefore, the KCAPS-SF may be a practical tool to effectively and efficiently measure coping and adaptation in people dealing with stressful conditions. It is expected that using the KCAPS-SF for Korean patients with cancer who experience ill health conditions will lead to systematic coping-related research. Future research could investigate changes in coping strategy over time and identify specific nursing intervention periods. In addition, research can compare the level of coping across various cancer diagnoses and treatment methods within the same diagnosis.

However, this study has the following limitations. First, since this study sampled cancer patients in only one province, further studies should be conducted on cancer patients in various regions in order to obtain a more generalized view of the use of the KCAPS-SF in clinical practice. In addition, this tool was developed for cancer patients, but the subjects were patients with hematologic malignancies; therefore, patients with solid tumors were not included in this study. Medical factors (i.e., type of cancer, time since diagnosis, and whether the cancer was currently being treated) were additional possible influences on coping strategies among cancer patients. Further studies are needed to revalidate the validity and reliability of the instruments for cancer patients who have been diagnosed with various types. Second, since there are 15 items on the CAPS-SF, 164 participants represented the ideal sample size according to the EFA standard, but a sample of this size was not adequate for CFA. Further study is needed to re-verify the instrument's CFA by increasing the number of subjects. Finally, this study did not test responsiveness, which evaluates changes in the degree of patient-reported coping over time. Therefore, responsiveness needs to be assessed in a future longitudinal study.

CONCLUSION

Patients with cancer experience various physical and psychological symptoms in the course of diagnosis and treatment, while coping effectively influences patients' QoL and adaptation. Therefore, it is very important to gain an objective understanding of the coping strategies used by patients with cancer. Accordingly, the present study was conducted to test the validity and reliability of the 15-item KCAPS-SF. The results indicated that the 15-item KCAPS-SF achieved satisfactory validity and reliability. However, this study did not include a variety of different cancer patients, and it may not have included a sufficient number of subjects. Given that these issues can be improved in subsequent research, the KCAPS-SF will serve as a useful measure within clinical settings to assess coping strategies that affect QoL and adaptations for patients with cancer in Korea.

This paper was supported by international research funds for humanities and social science from Chonbuk National University in 2015.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Appendix

References

-

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Cognitive theories of stress and the issue of circularity. In: Appley MH, Trumbull R, editors. Dynamics of Stress: Physiological and Social Perspectives. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 63-80.

-

-

Aldwin CM. In: Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 32-149.

-

-

Holland KD, Holahan CK. The relation of social support and coping to positive adaptation to breast cancer. Psychol Health 2003;18(1):15–29. [doi: 10.1080/0887044031000080656]

-

-

Roy C. In: The Roy adaptation model. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Education, Inc.; 2009. pp. 29-124.

-

-

Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, Phelps AC, Block SD, Ng AK, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 2012;10(2):81–87. [doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003]

-

-

Jalowiec A. Coping with illness: Synthesis and critique of the nursing coping literature from 1980–1990. In: Barnfather JS, Lyon BL, editors. Stress and Coping: State of the Science and Implications for Nursing Theory, Research and Practice. Indianapolis (IN): Center Nursing Press; 1993. pp. 65-83.

-

-

Hair JF Jr, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. In: Multivariate data analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall; 2010. pp. 578-581.

-

-

Kim H, Yoo HJ, Kim YJ, Han OS, Lee KH, Lee JH, et al. Development and validation of Korean Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Korean J Clin Psychol 2003;22(1):215–229.

-

-

Khalili N, Farajzadegan Z, Mokarian F, Bahrami F. Coping strategies, quality of life and pain in women with breast cancer. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2013;18(2):105–111.

-

-

Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol 1970;1(3):185–216. [doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301]

-

-

Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WL, Berry JW, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage; 1986. pp. 137-164.

-

-

Chayaput P. In: Development and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of the coping and adaptation processing scale [dissertation]. Boston (NY): Boston College; 2004. pp. 1-200.

-

-

Kim GS. In: Analysis structural equation modeling. Seoul: Hannarae Publishing Co.; 2010. pp. 191-387.

-

-

Fayers PM, Machin D. In: Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and reporting of patient-reported outcomes. 3rd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2016. pp. 134-136.

-

-

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. In: Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. pp. 248-278.

-

-

Chayaput P, Roy C. Psychometric testing of the Thai version of the coping and adaptation processing scale-short form (TCAPS-SF). Thai J Nurs Counc 2007;22(3):29–39.

-

-

Gutiérrez López C, Veloza Gómez MDM, Moreno Fergusson ME, de Villalobos D, Mercedes M, López de Mesa C, et al. Validity and confidence level of the Spanish version instrument of Callista Roy Coping Adaptation Processing Scale. Aquichán 2007;7(1):54–63.

-

-

Park HA. Problems and issues in developing measurement scales in nursing. J Nurs Query 2005;14(1):46–72.

-

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite