Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 51(6); 2021 > Article

- Research Paper The Influence of Family Function on Occupational Attitude of Chinese Nursing Students in the Probation Period: The Moderation Effect of Social Support

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2021;51(6):746-757.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21103

Published online: December 31, 2021

2College of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

3Rehabilitation College, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

4College of Chinese medicine, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

5Innovation Practice Center, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, China

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore the factors influencing the occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period.

Methods

Nursing students in the probation period from five hospitals completed an anonymous survey. The instruments included the nursing occupational attitude scale, family adaptability, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve index, and perceived social support scale. The study examined the moderation model between family function, perceived social support, and occupational attitudes using PROCESS 3.2.

Results

For nursing students, when social support was low, family function had a significant positive impact on occupational attitudes and intentions, and the effect was much higher than that of perceived social support.

Conclusion

Family function has a significant positive explanatory effect on attitude and intention (β = .13, p < .001 and β = .12, p < .001); the interaction term between family function and perceived social support are significant (β = .01, p < .001 and β = .01, p < .001). Perceived social support has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between family function and occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period. Family function has a significant difference in the occupational attitudes and intentions of nursing students with low perceived social support. Nursing students perceive social support in the probation period has a significant moderation effect in the relationship between their family function and occupational attitudes. Interns with low family function should be given more social support to improve their occupational attitudes.

Published online Dec 08, 2021.

https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21103

The Influence of Family Function on Occupational Attitude of Chinese Nursing Students in the Probation Period: The Moderation Effect of Social Support

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore the factors influencing the occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period.

Methods

Nursing students in the probation period from five hospitals completed an anonymous survey. The instruments included the nursing occupational attitude scale, family adaptability, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve index, and perceived social support scale. The study examined the moderation model between family function, perceived social support, and occupational attitudes using PROCESS 3.2.

Results

For nursing students, when social support was low, family function had a significant positive impact on occupational attitudes and intentions, and the effect was much higher than that of perceived social support.

Conclusion

Family function has a significant positive explanatory effect on attitude and intention (β = .13, p < .001 and β = .12, p < .001); the interaction term between family function and perceived social support are significant (β = .01, p < .001 and β = .01, p < .001). Perceived social support has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between family function and occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period. Family function has a significant difference in the occupational attitudes and intentions of nursing students with low perceived social support. Nursing students perceive social support in the probation period has a significant moderation effect in the relationship between their family function and occupational attitudes. Interns with low family function should be given more social support to improve their occupational attitudes.

INTRODUCTION

There is a shortage of nurses in many countries worldwide [1]. According to the predictions made by scholars on the current status and future needs of nursing staff in the United States in 2019, there will be a shortage of up to one million nursing staff in the United States by 2030 [2]. The percentage of active nurses with turnover intention was as high as 41.9% in Japan, and the actual turnover rate was approximately 11.2% [3]. In South Korea, the average turnover rate of nurses was 16.9% [4]. A survey on the turnover of hospital nurses in Guangdong Province showed that 7.7% of the hospitals had a turnover rate of more than one-tenth from 2011 to 2014 [5]. The State of the World’s Nursing [6] points out that the current number of nurses in the world is less than 28 million, which is far from meeting the global demand for medical services. There is a shortage of 5.9 million nurses worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a wake-up call regarding the global shortage of nurses [7].

Nurses’ occupational attitudes have a significant correlation with their turnover intention [8]. Occupational attitude is the tendency of cognition, evaluation, and lasting psychological response to a certain occupation [9]. In the field of nursing profession, it refers to the individual’s cognition and evaluation of the content of nursing work, the status and role of nursing work in society, the quality requirements of nurses, and the characteristics of nurses’ labor; and the resulting emotional experience and behavioral tendencies. The occupational attitudes of nurses were usually analyzed from three perspectives: knowledge, attitude, and intention to engage in nursing work [10]. Studies have shown that occupational attitude is an important determinant of nurses’ perseverance in their jobs, which could reduce their turnover intention by optimizing personal professional identity [11]. Poor occupational attitudes also reduced their professional satisfaction and made them reluctant to continue their work. These did not occur only in experienced nurses. For nursing students in the learning stage, their occupational attitudes played an important role in whether they chose to engage in nursing work and whether they would persist in nursing work in the future [12]. These effects were particularly strong for nursing students who had already started nursing practice [13].

The occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period are affected by factors such as stress perception, professional interest, self-perception, role model, and self-worth [14]. A study with a sample of 249 middle-aged South Koreans showed that among these influencing factors, stress perception and self-perception were positively correlated with family function and were significantly predicted by it [15]. The result-oriented view believed that family function was the emotional connection, communication, and the ability to effectively deal with external events between family members [16]. It was reflected in the interaction quality between individuals, family intimacy, adaptability, and other dimensions [17]. A sound family function promotes an individual’s physical and mental health, is conducive to their growth and development, and affects their career choices [18]. Family function is the guarantee for individuals to carry out normal social activities, and is positively correlated with college students’ occupational attitudes and development [19]. A study of 420 South Korean college students has shown that family functions have a positive effect on career preparation, decision-making, development, and attitudes [20]. With the protection of family functions, nurses balanced work and family, and maintained good working conditions [21]. Previous researchers have investigated Chinese clinical nurses to explore empathic fatigue and related emotional experiences in nursing. The results revealed that the enhancement of the family functions of clinical nurses was helpful in improving the emotional experience of nursing work, helped nurses better adapt to clinical work, and improved nurses’ experience in practice. They were more adaptable to clinical work [22]. This suggests that family functioning may be an effective factor in improving nurses’ attitudes toward clinical work. In Asian countries such as China, it is a traditional and universal virtue to provide more care for the elderly and children in the family. Relatively little family care is provided to young adults [23]. Could this be a causal factor for the poor professional attitudes of nursing students? However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the direct effect of family functions on nursing occupational attitudes.

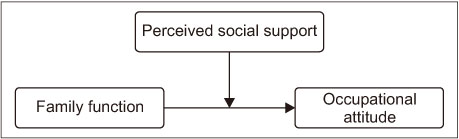

Social support is another factor that has a positive impact on occupational attitudes. It refers to the spiritual and material support that an individual receives from the relationships that they have [24]. Social support reduced nurses’ work stress and improved their mental health [25], thus exerting an influence on their occupational attitudes. Social support has also been proven to be related to the family function, which could compensate for the lack of family functions to a certain extent [26]. A study exploring the relationship between psychological symptoms, social support, and family function in older adults noted that the support older adults receive from friends, neighbors, and organizations can compensate for their lack of family functioning due to widowhood or other problems, thereby reducing their psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression [27]. This compensation was not only financial, but also emotional [28]. The social cognitive career theory (SCCT) points out that occupational attitudes are affected by personal and environmental variables. Background environmental factors such as socioeconomic status and family care directly affect occupational attitudes and behaviors, while social function and other environmental factors that are most related to professional behavior can moderate them [29]. For example, impairments in family functioning such as poor family patterns and unmet care needs create negative learning experiences for individuals, which in turn shape their low attitudes toward their careers. However, when individuals receive more support and encouragement from society, this damage is effectively mitigated [30]. Previous studies have revealed the moderating effect of social support on attitudes [31]. To date, there has been no research on whether social support could be used as an intermediate variable to moderate the relationship between family function and nursing occupational attitudes. This is the focus of this study. We constructed a theoretical model based on the SCCT theory, as shown in Figure 1. In the model, we use ‘perceived social support’ as an indicator of the social support received by the individual.

Figure 1

The theoretical model.

1. Purpose and hypothesis

We used Chinese nursing students in the probation period as the survey subjects to investigate the impact of family functions on occupational attitudes and the moderating effect of social support, with the goal of providing a reference for relevant departments to formulate measures to improve nursing students’ occupational attitudes.

The hypotheses are proposed as follows: 1) Nursing students with high family function are likely to have high occupational attitudes. 2) Social support plays a moderating effect between family function and occupational attitudes.

METHODS

1. Study design and Sample

Study design was a cross-sectional study. In January 2021, we adopted a cluster sampling to select fourth-year nursing undergraduates who were interns in five tertiary and one general hospitals in Changchun, China. More than 50 nursing students in the probation period were selected from each hospital. Volunteers who participated in this survey and those who were interns in the hospital for more than three months were included. Those who were not in the hospital during the investigation were excluded. According to the Kendall criterion, in the estimation of the number of sample cases in a multivariate analysis, the number of observations is at least 10 times the number of variables [32]. This study involved 21 variables; therefore, at least 210 questionnaire surveys were required. A total of 408 questions were distributed in this survey, and 394 valid questions were returned. The effective response rate was 96.6%. The average age of the respondents was 22.8 years (SD = 1.52, the entire range was 21~24), including 56 men (14.2%) and 338 women (85.8%). From the perspective of family location, the number of families in cities, towns, and rural areas were 123 (31.2%), 83 (21.1%), and 188 (47.7%), respectively.

2. Measures

1) Nursing occupational attitude scale

The nursing occupational attitude scale compiled by Rossiter et al. [10] was used. The scale contained three dimensions of nursing occupational knowledge (11 items), attitude (8 items), and intention (8 items); and a total of 27 items. Five-point Likert scales measuring the strength of agreement were used with one for “strongly disagree” and five for “strongly agree.” Higher scores of each dimension represent more positive acts on basic cognition of nursing work, attitudes toward nurses’ identity and work content, and their willingness to engage in nursing work. The total score of the three dimensions evaluated the overall occupational attitude of nurses and nursing students. A high score indicated a better attitude toward the nursing occupation. Cronbach’s α for each dimension were .78, .71, and .87, respectively, and for total item, .82 in this study.

2) Family function scale

The family adaptability, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve (APGAR) index questionnaire compiled by Smilkstein [33] was used to measure the family function status. APGAR is a simple questionnaire used to test family functions. It has five questions, each of which represents a family function (adaptation, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve). Each item consisted of three options: “often”, “sometimes”, and “almost rarely”, each with a score of two to zero. A higher score indicates better family function. In this study, Cronbach’s α was .82.

3) Perceived social support scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale compiled by Zimet et al. [34] was used to measure the respondents’ perceived social support. There were 12 items on the total scale. Seven-point Likert scales measuring the strength of agreement were adopted, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with one to seven points, respectively. A higher score indicated more perceived social support. In this study, Cronbach’s α was .91.

4) Procedure

We sent three trained investigators. They visited five hospitals between January 11 and 15, 2021. Under the guidance of the hospital’s trainee management staff, they distributed questionnaires to nursing students in the probation period. The investigators explained in detail the purpose of the survey and provided instructions for completing the questionnaire. The nursing students completed and returned the questionnaires anonymously on site.

5) Data analysis

The data from the survey were coded and analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the groups. The correlations among the variables were calculated using bivariate correlation analysis. The moderation effect was verified using PROCESS 3.2 [35]. Nonparametric bootstrap and Sobel tests were used to examine the moderation effects with the plug-in. The sample size was 5,000, and the confidence interval was 95.0% [36]. All statistical tests used gender as the control variable, except for t-tests.

6) Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital to Changchun University of Chinese Medicine (IRB: CCZYFYLL-SQ-2020-030). All respondents voluntarily participated in the research and promised to keep it confidential.

RESULTS

1. Descriptive statistics

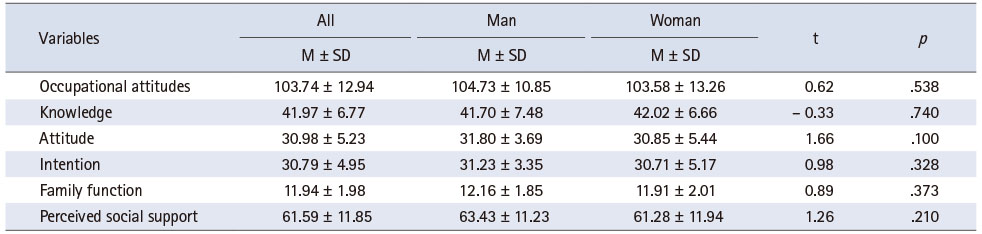

The mean value of the total score of the occupational attitudes of nursing students was 103.74 ± 12.94. In Table 1, the item with the lowest score is “shift work does not bother me” (3.55 ± 1.10) in the intention dimension. The highest score appeared in the attitude dimension: “it is very fulfilling to see patients getting better” (4.14 ± 0.98). There were no statistical differences by gender in family function, perceived social support, occupational attitudes, and various dimensions of the nursing students.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of Occupational Attitudes, Family Function and Perceived Social Support

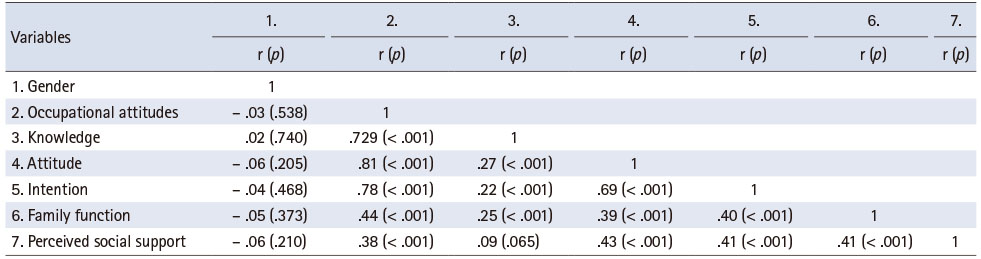

2. Correlation analysis

There were no correlation between gender and family function, perceived social support, occupational attitudes, and their various dimensions. Family function had a significant positive correlation with perceived social support, occupational attitudes, and their various dimensions. Perceived social support was significantly positively correlated with occupational attitudes and their two dimensions (attitude and intention), but did not correlate with the dimension of knowledge (Table 2).

Table 2

Correlation Analysis of Gender, Occupational Attitudes, Family Function and Perceived Social Support

3. Moderating effect

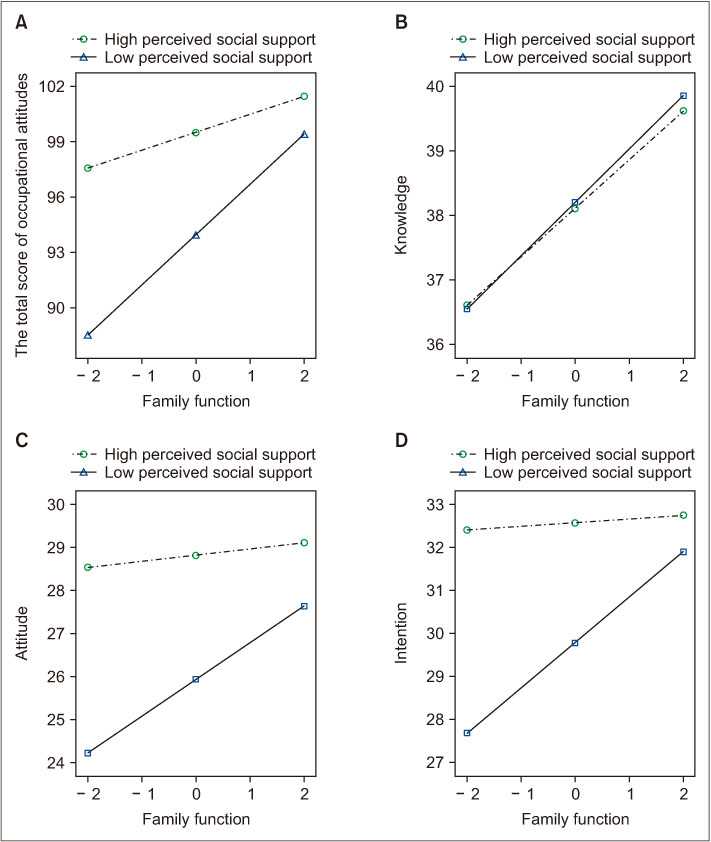

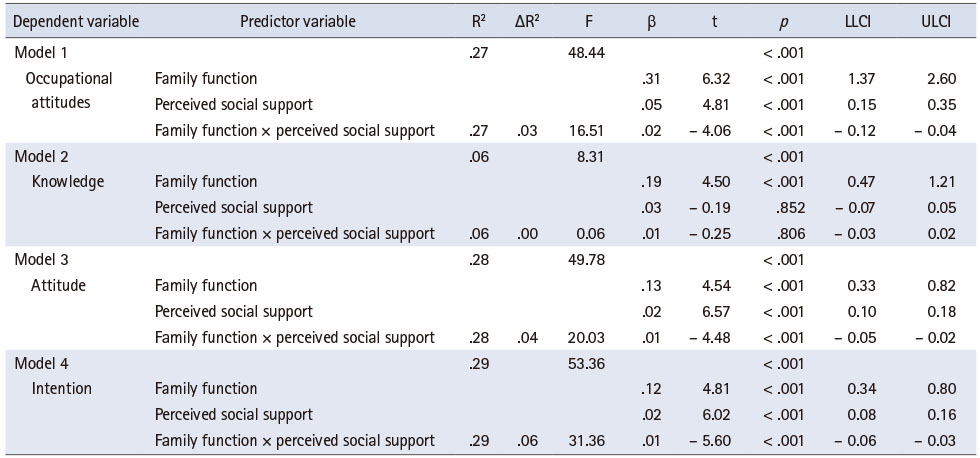

First, we took the total score of occupational attitudes as the dependent variable, family function as the independent variable, and perceived social support as the moderating variable to investigate whether social support could moderate the relationship between family function and occupational at-titudes (Model 1). According to the moderating effect test procedure recommended by Wen et al. [37], the independent and moderating variables need to be centrally processed. The product of the centralized independent variable and the moderating variable was calculated and included as an independent variable in the hierarchical regression. These procedures were automatically completed using PROCESS 3.2. Each model is significant at the .01 level. Family function and social support had significant main effects on the occupational attitudes and family function had a significant positive explanatory effect on occupational attitudes (β = .31, p < .001). Thus, hypothesis 1 is supported. The interaction term between family function and perceived social support was significant (β = .02, p < .001), indicating that perceived social support had a moderating effect on the influence of family function and occupational attitudes (Table 3). Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported. Figure 2 shows the moderating effect of perceived social support. In Figure 2, the criteria for grouping high and low social support comprehension are the mean plus or minus the standard deviation of the variable (± 11.85). The total score of occupational attitudes with different levels of perceived social support improved with an increase in family function. This trend was more significant at lower levels of perceived social support (Figure 2A).

Figure 2

Moderating effect of perceived social support. (A) Moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between family function and the total score of occupational attitudes. (B) Moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between family function and knowledge. (C) Moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between family function and attitude. (D) Moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between family function and intention.

Table 3

Moderating model test (the Total Score of Occupational Attitudes and Their All Dimensions Were Divided into Dependent Variables)

Further, with occupational knowledge (Model 2), attitude (Model 3), and intention (Model 4) as the dependent variables; family function as the independent variable; and perceived social support as the moderating variable, we investigated whether the moderating effect of perceived social support on family function and the three dimensions of occupational attitudes was established. The method was the same as above. The main effects of family function and perceived social support on attitudes and intentions were significant. Family function had a significant positive explanatory effect on attitude and intention (β = .13, p < .001 and β = .12, p < .001); the interaction term between family function and perceived social support were significant (β = .01, p < .001 and β = .01\xef\xbc\x8c p < .001). Social support had moderating effects on the influence of family function on attitude and intention. However, in the knowledge dimension, perceived social support did not show a significant explanatory effect. The interaction between family function and perceived social support was also insignificant. Perceived social support had no moderating effect on the influence of family function on occupational knowledge (Table 3).

The moderating effect of perceived social support is shown in Figure 2C, 2D. When the level of perceived social support was low, with an improvement in the family function, the attitudes and intentions of nursing students showed a significant upward trend. A higher level of perceived social support led to a more significant positive impact of family function on them. However, as shown in Figure 2B, there was no significant difference in the trend of occupational knowledge growing with family function under high or low levels of perceived social support. The relationship between family function and occupational knowledge was not moderated by the level of perceived social support.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that the mean value of the total score of the occupational attitudes of nursing students is significantly lower than the scores reported in the previous literature for nursing students in school (111.13 ± 13.84, p < .001) [37]. The total scores of occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period were lower than those of nursing students at university, as reported in previous studies (p < .01). This is consistent with the results of existing studies. Another study reported similar results [39]. The study concluded that the results were due to the fact that the perceptions of nursing students at university reported changed more significantly during their clinical practice as they continued to learn more about nursing and experience it firsthand. Compared with universities, the learning environment in hospitals is complex and tiring. Nursing students often can not adapt to the full-time work in the hospitals immediately after starting the graduation internship. These may be the reasons for the decline in the occupational attitude level of nursing students in the probation period [40]. For many nurses, shift work was tiresome and exhausting [13]. In this survey, attitude toward shift work was one of the items that examined nursing students’ occupational intention. The low evaluation of this kind of work style had a negative impact on the occupational intention and overall occupational attitude of nursing students. This is worthy of attention from internship planners. It is possible to improve the occupational attitudes of nursing students by implementing a more humane shift work plan. In the attitude dimension, the items that reflected the interns’ sense of accomplishment and compassionate love for patients received high scores, showing the most positive elements in their nursing occupational attitudes. This result was consistent with the results of a study conducted of experienced nurses [41]. Interventions for them should be targeted, rather than universal.

The family is the harbor of an individual in society. In the family, people’s injuries are comforted and ideals are supported. Good family functions provide continuous power to people’s social activities [19]. In this study, family functions were significantly positively correlated with knowledge, attitudes, and intentions. In the test of the moderating effect, family function had explanatory effects on all three factors. These trends were also reflected in other occupational fields; for example, female teachers with well-functioning families had less stress and more positive occupational attitudes [42]. Further, nursing students who got more family care had a more positive attitude toward nursing work. They had richer knowledge of nursing and showed a stronger intention to engage in nursing work.

In this study, nursing students in the probation period who perceived higher-level social support got higher scores in occupational attitudes and the other two dimensions, except for knowledge. Previous studies on critical incidents among intensive care unit nurses have also obtained similar results. Nurses who received less social support in critical incidents experienced greater burnout and injury. They showed a more negative attitude toward work and a stronger desire to resign [43]. The study noted that this situation is detrimental to overall nursing care and needs to be improved in terms of enhancing social support as well as other aspects.

The lack of social support has become one of the main factors that trigger the turnover intention of newly graduated nurses [44]. Studies in other occupational fields have also shown that the perception of social support felt by individuals is closely related to their occupational attitudes [45]. An effective social support system and high satisfaction with social support were conducive to improving the occupational attitudes of individuals and reducing their turnover intention.

Knowledge, as another dimension of occupational attitudes, did not show any relevance to social support in this study. Previous studies have shown that nursing students’ knowledge in the probation period mainly reflects their early learning level of nursing knowledge and skills in the university classroom [46]. The learning outcomes in the classroom are not closely related to the social support that students perceive [47]. However, this part of the conclusion is controversial. There are also pieces of literature reporting the positive effect of social support on learning outcomes [48], but there is a lack of research with nursing students as the survey subject. Therefore, the relationship between the social support perceived by nursing students and their professional knowledge needs to be further studied.

The results of this study indicated that social support had a moderating effect on the relationship between family function and the two dimensions of nursing students’ occupational attitudes in the probation period. In other words, the pattern of relationship between family function and attitude or intention was different among nursing students with high or low levels of social support. The slope chart shows that compared to nursing students with high social support levels, nursing students with low social support levels were more satisfied with family functions, their professional attitudes were better, and their intention to engage in nursing work was stronger. The role of family function on occupational attitudes and intention of nursing students with low social support levels had significantly increased. This indicated that both social support and family function were important factors affecting nursing students’ occupational attitudes, and the two roles complemented each other. Effective social support and family functions provided individuals with a sufficient sense of security and belonging. Therefore, individuals could avoid the psychological impact of fatigue, burnout, and other adverse stimuli [48]; alleviate their negative physical and mental reactions; and reduce the negative emotions generated during the internship. At the same time, social support and family care helped individuals experience a sense of accomplishment [49]. Individuals who were spiritually and materially replenished by adequate social support were more likely to develop compassionate love for others [50] and positive occupational attitudes, and enhance their occupational intentions.

Nursing students in the probation period are the main force in establishing an occupational and high-quality nursing team in the future. Exploring the influencing factors of their occupational attitudes is beneficial for not only improving the stability of the nursing team but also promoting the sustainable development of the nursing career. This study clarified the positive effect of family function on nursing occupational attitudes. Therefore, to improve their occupational attitude, nursing students in the probation period need to participate in improving their family function to obtain more family support. For family members of nursing students, it is necessary to create a harmonious family atmosphere as much as possible, provide their children with sufficient care, and solve problems together. Hospitals and universities should also provide more rest time and emotional care for nursing students, reduce their work intensity, ease their work pressure, and meet the needs of their family function. The more important conclusion of this study is the discovery of the moderating effect of social support between family function and occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period. Improvement in family function is often complicated and slow [17]. Therefore, it is necessary to provide more social support to nursing students with low family function. Universities and internship hospitals should pay attention to the psychological problems of nursing students and the problems existing in their family functions to provide targeted support. Specific measures can be considered from two aspects. The first is to provide instrumental support. This includes assisting nursing students in establishing a support network in the workplace and providing necessary guidance and assistance so that they can quickly obtain the information and services they require; it also includes providing tangible support, such as increased financial subsidies, increased opportunities for further study, and so on. The second is to provide expressive support, such as establishing a psychological consultation mechanism for nursing students on probation to provide psychological and emotional support; to improve their occupational attitudes, we should focus on maintaining nursing students’ self-esteem and providing them with appropriate recognition at work. Nursing students should seek help from their families, universities, and hospitals as soon as possible when faced with obstacles to their career development to improve their occupational attitudes and succeed in their careers.

This was a cross-sectional data study. Our sample came from the same city, and its size and diversity were limited. Whether the results applied to nursing students in the probation period in other regions remains to be discussed. In a single survey, it was difficult to capture the dynamic process of nursing students’ family function, perceived social support, and occupational attitude; and their internal causality. A limitation of this study is that work-related or work environment was not considered in this study. This factor should be fully considered in future research. Additionally, this study adopted a questionnaire survey. Inspection points for family function and occupational attitudes may be more limited. As a result, qualitative research methods such as interviews are required to conduct a more in-depth study on these factors among nursing students in the probation period.

CONCLUSION

Perceived social support had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between family function and occupational attitudes of nursing students in the probation period. Family function had a significant difference in the occupational attitudes and intentions of nursing students with low perceived social support. The occupational attitudes could be improved through the targeted strengthening of the family function of nursing students with low perceived social support or the social support of nursing students with low family function, and encouraging them to be more active in nursing work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:The authors declared no conflict of interest.

FUNDING:This study was supported by the National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program in 2020 fund in Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (NO.202010199004), and Research Project on Teaching Reform of Vocational Education and Adult Education in Jilin Province fund in Jilin Provincial Department of Education (NO. 2020ZCY344).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: Wang W.

Data curation or/and Analysis: Wang W & Tang R.

Funding acquisition: Wang W.

Investigation: Tang R & Li Z & Jiang H.

Project administration or/and Supervision: None.

Resources or/and Software: Liu X.

Validation: Li R.

Visualization: Li R.

Writing original draft or/and Review & Editing: Li R.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

References

-

Shi R, Liu Y, Zhang Z. The turnover status of nurses in tertiary hospitals of Guangdong province. Chinese Nursing Management 2016;16(11):1503–1506.Chinese.

-

-

World Health Organization (WHO). State of the world's nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. pp. 37-43.

-

-

Kerzman H, Van Dijk D, Siman-Tov M, Friedman S, Goldberg S. Professional characteristics and work attitudes of hospital nurses who leave compared with those who stay. Journal of Nursing Management 2020;28(6):1364–1371. [doi: 10.1111/jonm.13090]

-

-

Huijts PM, de Bruijn E, Schaap H. Revealing personal professional theories. Quality & Quantity 2011;45(4):783–800. [doi: 10.1007/s11135-010-9322-z]

-

-

Tong C. Empirical study on the relationship between occupational stress, turnover tendency and working attitude of grassroots health workers in Liaoning province. Medicine and Society 2021;34(2):113–117. [doi: 10.13723/j.yxysh.2021.02.023]Chinese.

-

-

Bahçecioğlu Turan G, Özer Z, Çiftçi B. Analysis of anxiety levels and attitudes of nursing students toward the nursing profession during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2021;57(4):1913–1921. [doi: 10.1111/ppc.12766]

-

-

Midilli TS, Kirmizioglu T, Kalkim A. Affecting factors and relationship between patients’ attitudes towards the nursing profession and perceptions of nursing care in a university hospital. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2017;67(7):1059–1064.

-

-

Yeom HE, Park E, Jung M. Impact of family function on the relationship between self-perception of aging and stress in midlife. Innovation in Aging 2019;3 Suppl 1:S459 [doi: 10.1093/geroni/igz038.1718]

-

-

Olson DH. Circumplex Model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy 2000;22(2):144–167. [doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00144]

-

-

Beavers R, Hampson RB. The Beavers Systems Model of Family Functioning. Journal of Family Therapy 2002;22(2):128–143. [doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00143]

-

-

Zernov DV, Iudin AA, Ovsyannikov AA. Social well-being of the Soviet and Post-Soviet students. Narodonaselenie 2015;2015(1):50–68.

-

-

Kim S, Ahn T, Fouad N. Family influence on Korean students’ career decisions: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Career Assessment 2016;24(3):513–526. [doi: 10.1177/1069072715599403]

-

-

Tian M, Shi Y, Li H, Wang J. Qualitative study on emotional experience associated with compassion fatigue and its coping strategy in clinical nurses. Chinese Journal of Modern Nursing 2017;23(4):476–481.Chinese.

-

-

Cao J. In: Education of children in an ethic of care perspective. Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University; 2019. pp. 25-27.

-

-

Almeida LY, Carrer MO, Souza J, Pillon SC. Evaluation of social support and stress in nursing students. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da U S P 2018;52:e03405 [doi: 10.1590/S1980-220X2017045703405]

-

-

Odoardi I, Furia D, Cascioli P. Can social support compensate for missing family support? An examination of dropout rates in Italy. Regional Science Policy & Practice 2021;13(1):121–139. [doi: 10.1111/rsp3.12358]

-

-

Mo Q, Zhou L, He Q, Jia C, Ma Z. Validating the Life Events Scale for the Elderly with proxy-based data: A case-control psychological autopsy study in rural China. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2019;19(6):547–551. [doi: 10.1111/ggi.13658]

-

-

Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G. Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2000;47(1):36–49. [doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36]

-

-

Lent RW, Brown SD. Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. The Career Development Quarterly 1996;44(4):310–321. [doi: 10.1080/13669877.2017.1351472]

-

-

Herrero J, Urueña A, Torres A, Hidalgo A. Smartphone addiction: Psychosocial correlates, risky attitudes, and smartphone harm. Journal of Risk Research 2019;22(1):81–92. [doi: 10.1080/13669877.2017.1351472]

-

-

Kendall MG. In: Multivariate analysis. New York (NY): Hafner Press; 1975. pp. 40-41.

-

-

Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. The Journal of family practice 1978;6(6):1231–1239.

-

-

Bolin JH. Andrew F. Hayes (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Journal of Educational Measurement 2014;51(3):335–337. [doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050]

-

-

Rainone N, Chiodi A, Lanzillo R, Magri V, Napolitano A, Morra VB, et al. Affective disorders and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in adolescents and young adults with Multiple Sclerosis (MS): The moderating role of resilience. Quality of Life Research 2017;26(3):727–736. [doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1466-4]

-

-

Wen Z, Hau KT, Chang L. A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. Acta Psychologica Sinica 2005;37(2):268–274.Chinese.

-

-

Zhu K, Tang B, Xu L, Zhao L, Lan X. The professional attitude and psychological status of nursing undergraduates during Covid-19 pandemic containment: An investigation from mixed research perspective conducted at a University in Lishui. Journal of Lishui University 2021;43(2):36–43.Chinese.

-

-

Luo Y, Xiong Q. Comparative analysis on professional attitude of nursing students in school and nursing students in practice. Journal of Jianghan University (Natural Science Edition) 2020;48(3):50–56. [doi: 10.16389/j.cnki.cn42-1737/n.2020.03.008]Chinese.

-

-

Mousa AA, Menssey RFM, Kamel NMF. Relationship between perceived stress, emotional intelligence and hope among intern nursing students. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science 2017;6(3 Ver. II):75–83. [doi: 10.9790/1959-0603027583]

-

-

de Janasz S, Forret M, Haack D, Jonsen K. Family status and work attitudes: An investigation in a professional services firm. British Journal of Management 2013;24(2):191–210. [doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00797.x ]

-

-

Tei-Tominaga M. Factors related to the intention to leave and the decision to resign among newly graduated nurses: A complete survey in a selected prefecture in Japan. Environmental Health & Preventive Medicine 2013;18(4):293–305. [doi: 10.1007/s12199-012-0320-8]

-

-

Chung M, Jeon A. Social exchange approach, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in the airline industry. Service Business 2020;14(2):241–261. [doi: 10.1007/s11628-020-00416-7]

-

-

Gellerstedt L, Moquist A, Roos A, Karin B, Craftman ÅG. Newly graduated nurses’ experiences of a trainee programme regarding the introduction process and leadership in a hospital setting-a qualitative interview study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2019;28(9-10):1685–1694. [doi: 10.1111/jocn.14733]

-

-

Wu Y, Xue R, Wang X. Problems and the corresponding countermeasures in clinical nursing teaching. Clinical Research and Practice 2019;4(1):187–188. [doi: 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.201901086]Chinese.

-

-

Carmeli A, Peng AC, Schaubroeck JM, Amir I. Social support as a source of vitality among college students: The moderating role of social self-efficacy. Psychology in the Schools 2021;58(2):351–363. [doi: 10.1002/pits.22450]

-

-

Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Spiegel T, Nieboer AP. The associations of different social needs with psychological strengths and subjective well-being: An empirical investigation based on Social Production Function theory. Journal of Happiness Studies 2020;21(3):799–824. [doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00107-9]

-

-

Lee DS, Jiang T, Canevello A, Crocker J. Motivational underpinnings of successful support giving: Compassionate goals promote matching support provision. Personal Relationships 2021;28(2):276–296. [doi: 10.1111/pere.12363]

-

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite