Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 55(4); 2025 > Article

-

Research Paper

- A qualitative exploration of acute stroke patients’ experiences with aphasia in Korea

-

Jiyeon Kang1

, Hyunyoung Heo2

, Hyunyoung Heo2

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2025;55(4):621-633.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.25132

Published online: November 25, 2025

1College of Nursing, Dong-A University, Busan, Korea

2Stroke Care Unit, Dong-A University Hospital, Busan, Korea

- Corresponding author: Hyunyoung Heo Dong-A University Hospital, 26 Daesingongwon-ro, Seo-gu, Busan 49201, Korea E-mail: auvoir@naver.com

© 2025 Korean Society of Nursing Science

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) If the original work is properly cited and retained without any modification or reproduction, it can be used and re-distributed in any format and medium.

- 1,248 Views

- 129 Download

Abstract

-

Purpose

- This study aimed to explore the lived experiences of patients with acute stroke-related aphasia within the Korean healthcare context.

-

Methods

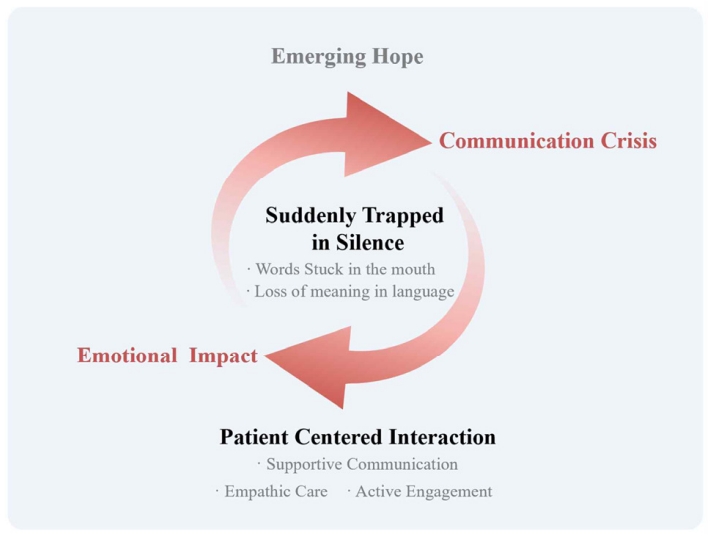

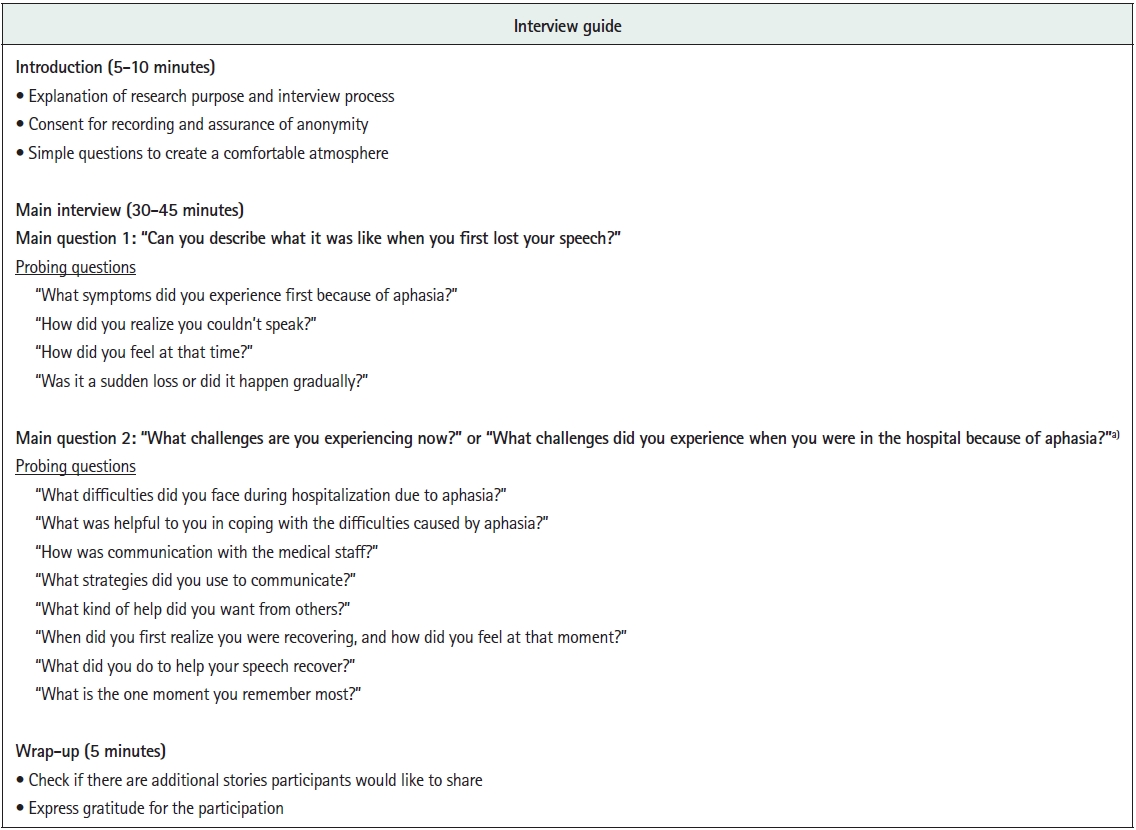

- A qualitative research design using inductive content analysis was employed, following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines. Fourteen adults with acute stroke-related aphasia participated in one-on-one, in-depth interviews conducted between January and May 2025. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling until theoretical saturation was reached. Data were analyzed using an inductive qualitative content analysis approach.

-

Results

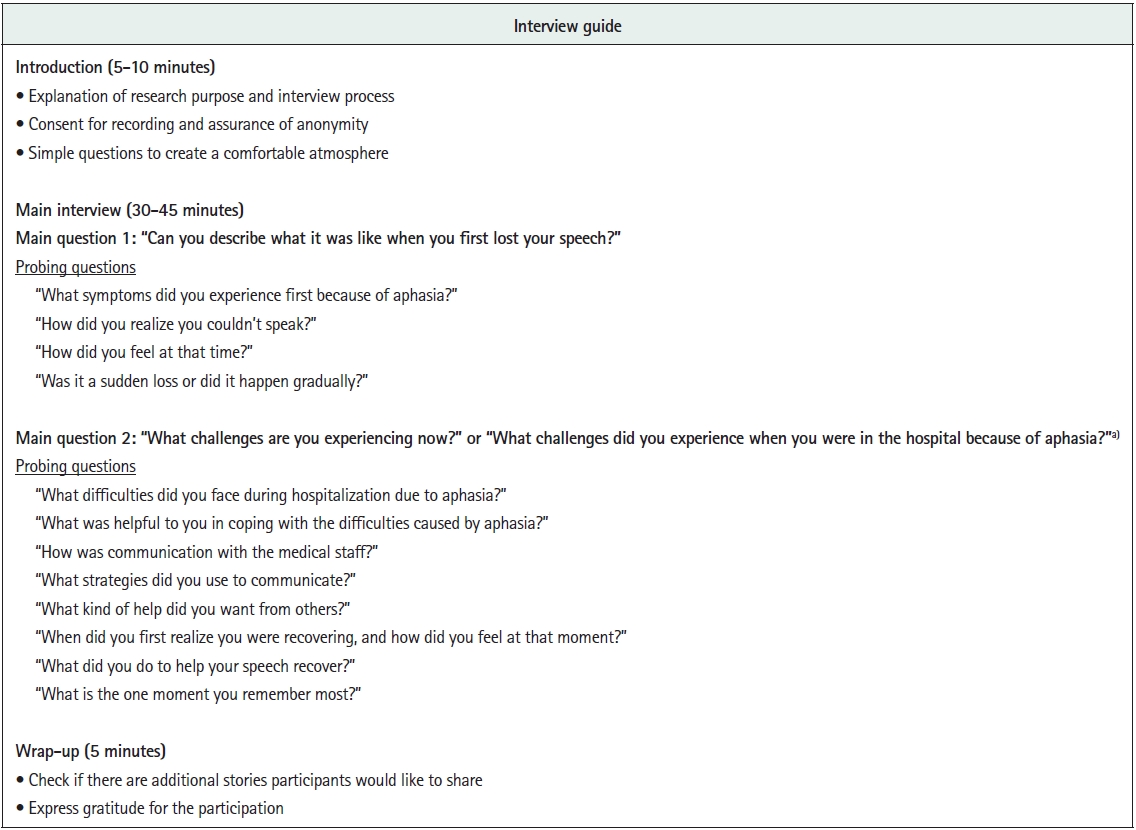

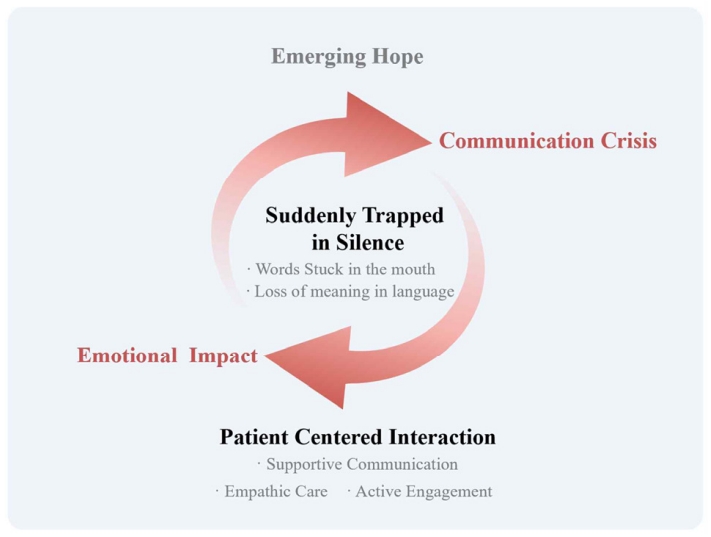

- Five main categories emerged: “suddenly trapped in silence” described the abrupt loss of language, including the inability to articulate intended words and understand others; “emotional impact” captured psychological shock and feelings of loss; “communication crisis” encompassed expressive difficulties, exclusion from decision-making, and social withdrawal; “patient-centered interaction” highlighted supportive communication, empathic care, and active engagement by others; and “emerging hope” reflected signs of recovery, self-directed efforts, and anticipation of improvement. These categories converged into the overarching theme, “communication beyond language,” illustrating how patients sought meaningful interaction despite linguistic limitations.

-

Conclusion

- Acute aphasia extends beyond a language disorder to encompass profound emotional and social experiences. Although communication barriers exist, meaningful interaction remains possible through empathetic, person-centered approaches. Healthcare professionals should recognize that patients with aphasia retain cognitive competence despite expressive limitations. These findings underscore the need to integrate emotional sensitivity into clinical care and to develop training programs that enhance person-centered communication skills in stroke rehabilitation settings.

Introduction

Methods

Results

1) Category 1: Suddenly trapped in silence

(1) Words stuck in the mouth

“It felt like the process of saying, ‘Daddy’s girl, let’s wash,’ was already in my brain, but the words would not come out. It just stopped here (pointing to his mouth). It wouldn’t progress beyond ‘Da… Da… Da….’ Why wasn’t it working? Why? It was so frustrating, constantly feeling this way.” (P6, M/35, 3 days after onset)

(2) Loss of meaning in language

“At first, I couldn’t understand anything—it was just buzzing sounds. As I gradually improved, I was able to catch words little by little. I tried reading books, but the readability was so poor. I tried to read a book called The Vegetarian, but I couldn’t understand it at all. The readability was poor, and even when I watched YouTube, I still couldn’t make sense of it.” (P2, M/49, 2 days after onset)

2) Category 2: Emotional impact

(1) Psychological shock

“For a moment—really, just for a moment—I was completely speechless. ‘Oh my God, I really cannot speak.’ I was so worried, thinking, ‘What should I do?’… No, I just couldn’t speak, so I thought, ‘Oh my God, what should I do? I guess I can’t speak. I guess I’m really becoming mute…’ My life is just over, it’s over. If I can’t speak, isn’t it completely over now?” (P10, F/72, 3 days after onset)

(2) Feeling lost

“It was the day I disappeared. The day I disappeared. Why am I here? Why am I alive? The first thing that came to my mind was, ‘How can I, who can’t speak, live? How could I live without speaking?’ My children were young, so I worried about finances. I felt lost, afraid of becoming a burden to them. Would my family have to support me? Why am I even here? I was out of my mind.” (P1, F/51, 8 days after onset)

3) Category 3: Communication crisis

(1) Difficulties in expression

“I wanted to tell them to take me to the bathroom because I needed to go, but the words wouldn’t come out. They just wouldn’t come out of my mouth. I kept saying it inside myself… but there was no one there, and I just ended up peeing. I kept trying to say, ‘I want to go to the bathroom, I want to go to the bathroom,’ but no one understood. I struggled so much, no matter how hard I tried. I really needed to go, but they didn’t take me… What should I say? I had already wet myself when I came in the ambulance, and it happened here at the hospital too. What should I say about this? I really wanted to say something, but I couldn’t… nothing came out.” (P7, F/81, 2 days after onset)

(2) Exclusion from decision-making

“The levin tube… was really mean. He just put it in without my consent. The tube went from my nose all the way down my throat, and it was so painful. If he had explained it to me in advance, I would have understood… But he just slammed the tube in without any explanation. That’s why I felt so bad. It was really bad.” (P8, M/64, 15 days after onset)

“When they talk to me, they act like I’m stupid or a baby… so it feels a little negative. I’m just an ordinary person, but they treat me like I’m stupid or a baby… so it feels a little frustrating.” (P2, M/49, 2 days after onset)

(3) Reluctance and withdrawal

“The nurse kept talking to me, and I was a little annoyed. I wanted to talk but I couldn’t, so it was annoying… No, it wasn’t that bad. I just got annoyed because I couldn’t speak, but she kept making me talk…” (P12, M/74, 5 days after onset)

4) Category 4: Patient-centered interaction

(1) Supportive communication

“There was no inconvenience. The doctors and nurses all waited patiently for me to speak. I found that incredibly kind. They said, ‘It’s okay. If you have anything to say, we’ll wait, so please speak slowly,’ and I was able to speak comfortably.” (P6, M/35, 3 days after onset)

(2) Empathic care

“I couldn’t speak, but the nurses did everything for me. They took care of everything… Even when I was lying down like this, they changed my clothes. If my clothes rode up, they pulled them down for me. If my position was uncomfortable, they even turned me to the side.” (P9, F/63, 6 days after onset)

“When I heard that there was a problem, the only feedback that mattered was whether it would get better. I was really grateful when the doctor said it would get better, and I was thankful at that time (crying)…” (P6, M/35, 3 days after onset)

(3) Active engagement

“The effort to help me understand what I didn’t understand—trying to explain it step by step while mimicking it—was tremendous effort. I don’t think there’s anything more helpful to the patient than that. In my opinion, being there for the patient is the most important thing.” (P13, M/67, 3 days after onset)

5) Category 5: Emerging hope

(1) Gradual but inconsistent recovery

“I was trying to speak… and the words just came out. Oh my, I’m talking. The words just came out without me knowing. It wasn’t as clear as this, but my voice was still there.” (P10, F/72, 3 days after onset)

“When I swear, it comes out incredibly well. But I can’t even pronounce my own name properly.” (P6, M/35, 3 days after onset)

(2) Self-directed efforts

“So, when I’m on the phone, I have to say my name, and here (pointing to his head) it makes sense, but it doesn’t come out of my mouth, so I practice on my own… The name is the same, but the actual pronunciation is different every time. I’ve also tried saying other people’s names on my own. Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t work well.” (P13, M/67, 3 days after onset)

(3) Anticipation of recovery

“At first, I was so scared… but now that I can speak a little… I think things will get better. I’ll be okay.” (P2, M/49, 2 days after onset)

Discussion

Conclusion

-

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Acknowledgements

None.

-

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2022R1A2C1011917). The funding source had no role in the study design, analysis, data interpretation, or decision to submit for publication.

-

Data Sharing Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: JK, HH. Data curation or/and Analysis: JK, HH. Funding acquisition: JK. Investigation: HH. Project administration or/and Supervision: JK. Resources or/and Software: JK, HH. Validation: JK, HH. Visualization: JK, HH. Writing: original draft or/and Review & Editing: JK, HH. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Article Information

- 1. Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, Martins SO, Pandian J, Lindsay P, et al. World Stroke Organization: global stroke fact sheet 2025. Int J Stroke. 2025;20(2):132-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930241308142Article

- 2. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. National health insurance statistics: inpatient/outpatient data [Internet]. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 22]. Available from: https://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapMfrnIntrsIlnsInfoTab1.do

- 3. Code C. Aphasia. In: Damico JS, Müller N, Ball MJ, editors. The handbook of language and speech disorders. Wiley; 2021. p. 286-309. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119606987.ch14

- 4. Wu C, Qin Y, Lin Z, Yi X, Wei X, Ruan Y, et al. Prevalence and impact of aphasia among patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(5):104764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104764ArticlePubMed

- 5. Li TT, Zhang PP, Zhang MC, Zhang H, Wang HY, Yuan Y, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of the relationship between sex and the risk or incidence of poststroke aphasia and its types. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24(1):220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04765-0ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Jung SH. Stroke rehabilitation fact sheet in Korea. Ann Rehabil Med. 2022;46(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.22001ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Zanella C, Laures-Gore J, Dotson VM, Belagaje SR. Incidence of post-stroke depression symptoms and potential risk factors in adults with aphasia in a comprehensive stroke center. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2023;30(5):448-458. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2070363Article

- 8. Burfein P, Roxbury T, Doig EJ, McSween MP, de Silva N, Copland DA. Return to work for stroke survivors with aphasia: a quantitative scoping review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2025;35(5):1081-1115. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2024.2381874Article

- 9. Lazar RM, Minzer B, Antoniello D, Festa JR, Krakauer JW, Marshall RS. Improvement in aphasia scores after stroke is well predicted by initial severity. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1485-1488. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577338Article

- 10. Wilson SM, Eriksson DK, Brandt TH, Schneck SM, Lucanie JM, Burchfield AS, et al. Patterns of recovery from aphasia in the first 2 weeks after stroke. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62(3):723-732. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-18-0254ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Simmons-Mackie N, Kagan A, Chan M, Shumway E, Le Dorze G. Aphasia and acute care: a qualitative study of healthcare provider perspectives. Aphasiology. 2025;39(7):900-917. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2392900Article

- 12. Stone M, Wallace SJ, Copland DA, Cadilhac DA, Hill K, Purvis T, et al. Quality and outcomes of acute stroke care for people with and without aphasia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2025 Jul 18 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2025.07.007ArticlePubMed

- 13. Carragher M, Steel G, O'Halloran R, Lamborn E, Torabi T, Johnson H, et al. Aphasia disrupts usual care: “I’m not mad, I’m not deaf”: the experiences of individuals with aphasia and family members in hospital. Disabil Rehabil. 2024;46(25):6122-6133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2024.2324115ArticlePubMed

- 14. Loft MI, Mathiesen LL, Jensen FG. Need for human interaction and acknowledging communication: an interview study with patients with aphasia following stroke. J Adv Nurs. 2025;81(6):3129-3140. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16512ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Kim DY. Analysis of communication difficulties and coping strategies in chronic aphasia patients through in-depth interviews [master’s thesis]. Daegu: Daegu University; 2023.

- 16. Hur Y, Kang Y. Nurses’ experiences of communicating with patients with aphasia. Nurs Open. 2022;9(1):714-720. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1124ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001ArticlePubMed

- 18. Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002ArticlePubMed

- 19. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042ArticlePubMed

- 20. Stockert A, Kümmerer D, Saur D. Insights into early language recovery: from basic principles to practical applications. Aphasiology. 2016;30(5):517-541. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1119796Article

- 21. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet?: data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20(9):1408-1416. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281Article

- 22. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Establishing trustworthiness. In: Lincoln YS, Guba EG, editors. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications; 1985. p. 289-331.

- 23. Clancy L, Povey R, Rodham K. “Living in a foreign country”: experiences of staff-patient communication in inpatient stroke settings for people with post-stroke aphasia and those supporting them. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):324-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1497716ArticlePubMed

- 24. Simmons-Mackie N, Kagan A, Le Dorze G, Shumway E, Chan MT. Aphasia and acute care: a qualitative study of family perspectives. Aphasiology. 2025;39(6):733-745. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2373431Article

- 25. Moss B, Northcott S, Behn N, Monnelly K, Marshall J, Thomas S, et al. ‘Emotion is of the essence. … Number one priority’: a nested qualitative study exploring psychosocial adjustment to stroke and aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2021;56(3):594-608. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12616ArticlePubMed

- 26. Kao SK, Chan CT. Increased risk of depression and associated symptoms in poststroke aphasia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):21352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72742-zArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Baker C, Worrall L, Rose M, Ryan B. ‘It was really dark’: the experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology. 2020;34(1):19-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1673304Article

- 28. Murphy D, Hourston J, Freeman E, Hawker N, Morris-Haynes R. An evaluation of the validity of an aphasia friendly mood and anxiety measure for stroke patients. Aphasiology. 2025;39(4):500-513. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2361512Article

- 29. Anemaat LN, Palmer VJ, Copland DA, Binge G, Druery K, Druery J, et al. Understanding experiences, unmet needs and priorities related to post-stroke aphasia care: stage one of an experience-based co-design project. BMJ Open. 2024;14(5):e081680. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-081680ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Lamborn E, Carragher M, O’Halloran R, Rose ML. Optimising healthcare communication for people with aphasia in hospital: key directions for future research. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2024;12(1):89-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-024-00431-zArticle

- 31. Bright FAS, Reeves B. Creating therapeutic relationships through communication: a qualitative metasynthesis from the perspectives of people with communication impairment after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(12):2670-2682. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1849419ArticlePubMed

- 32. Loft MI, Volck C, Jensen LR. Communicative and supportive strategies: a qualitative study investigating nursing staff’s communicative practice with patients with aphasia in stroke care. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2022;9:23333936221110805. https://doi.org/10.1177/23333936221110805ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Pound C, Jensen LR. Humanising communication between nursing staff and patients with aphasia: potential contributions of the Humanisation Values Framework. Aphasiology. 2018;32(10):1225-1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1494817Article

- 34. Tilton-Bolowsky VE, Hillis AE. A review of poststroke aphasia recovery and treatment options. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2024;35(2):419-431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2023.06.010ArticlePubMed

- 35. Brady MC, Mills C, Prag Øra H, Novaes N, Becker F, Constantinidou F, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guideline on aphasia rehabilitation. Eur Stroke J. 2025 May 22 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873241311025ArticlePubMed

- 36. Hur Y, Kang Y. Communication training program for nurses caring for patients with aphasia: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):893. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02599-0ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Bailey DJ, Herget F, Hansen D, Burton F, Pitt G, Harmon T, et al. Generative AI applied to AAC for aphasia: a pilot study of Aphasia-GPT. Aphasiology. 2024 Dec 31 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2445663Article

- 38. Braley M, Pierce JS, Saxena S, De Oliveira E, Taraboanta L, Anantha V, et al. A virtual, randomized, control trial of a digital therapeutic for speech, language, and cognitive intervention in post-stroke persons with aphasia. Front Neurol. 2021;12:626780. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.626780ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

| No. | Gender/age (yr) | Diagnosis | Type of aphasia | Days from onset (day)a) | Residual language impairments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F/51 | Lt. MCA infarction | Motor aphasia | 8 | Present |

| 2 | M/49 | Lt. MCA infarction | Sensory aphasia | 2 | Present |

| 3 | M/48 | Lt. MCA infarction | Motor aphasia | 40 | Present |

| 4 | F/78 | Lt. MCA infarction | Global aphasia | 4 | Absent |

| 5 | F/39 | Transient ischemic attack | Motor aphasia | 2 | Absent |

| 6 | M/35 | Rt. MCA infarction | Motor aphasia | 3 | Absent |

| 7 | F/81 | Lt. MCA infarction | Global aphasia | 2 | Present |

| 8 | M/64 | Multiple infarction | Motor aphasia | 15 | Present |

| 9 | F/63 | Lt. MCA infarction | Motor aphasia | 6 | Present |

| 10 | F/72 | Lt. MCA infarction | Global aphasia | 3 | Absent |

| 11 | M/62 | Lt. MCA infarction | Global aphasia | 4 | Present |

| 12 | M/74 | Lt. MCA infarction | Global aphasia | 5 | Present |

| 13 | M/67 | Lt. MCA infarction | Motor aphasia | 3 | Present |

| 14 | M/56 | Rt. cortical ICH | Sensory aphasia | 7 | Present |

| Theme | Category | Sub-category | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication beyond language | Suddenly trapped in silence | Words stuck in the mouth | Clear words in mind |

| Speech flow blocked | |||

| Distorted speech output | |||

| Altered sensation in the lips | |||

| Loss of meaning in language | Speech perceived as meaningless sounds | ||

| Unable to understand even my own speech | |||

| Only lip movements perceived | |||

| Inability to read written text | |||

| Emotional impact | Psychological shock | Unexpectedness | |

| Confusion | |||

| Fear | |||

| A sense of life-ending despair | |||

| Feeling lost | Uncertainty about the future | ||

| Worries about making a living | |||

| Concerns about family | |||

| Self-pity | |||

| Communication crisis | Difficulties in expression | Inability to express basic needs | |

| Inability to engage in small talk | |||

| Incomplete expression of intentions | |||

| Misunderstandings | |||

| Exclusion from decision-making | Decisions discussed solely with caregivers | ||

| Being treated like a child | |||

| Reluctance and withdrawal | Speaking feels exhausting | ||

| Reluctance to speak | |||

| Giving up on speaking | |||

| Patient centered interaction | Supportive communication | Encouraged to speak slowly | |

| Being listened to patiently | |||

| Facilitating speech | |||

| Empathic care | Showing attentive concern | ||

| Providing anticipatory assistance | |||

| Instilling hope for recovery | |||

| Active engagement | Initiating interaction | ||

| Making efforts to sustain conversation | |||

| Emerging hope | Gradual but inconsistent recovery | Words suddenly come out and are heard | |

| Fluctuating speech ability | |||

| Different pace of recovery for words | |||

| Still clumsy speech | |||

| Self-directed efforts | Alternative communication | ||

| Speech practice | |||

| Reading and writing practice | |||

| Anticipation of recovery | Relief | ||

| From fear to hope |

F, female; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; Lt., left; M, male; MCA, middle cerebral artery; Rt., right. a)At the time of the interview.

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite