Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 55(1); 2025 > Article

-

Research Paper

- A qualitative meta-synthesis of the essence of patient experiences of dialysis

-

Soyoung Jang1

, Eunyoung E. Suh2

, Eunyoung E. Suh2 , Yoonhee Seok1

, Yoonhee Seok1

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2025;55(1):119-136.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24102

Published online: February 19, 2025

1College of Nursing, Kyungil University, Gyeongsan, Korea

2Center for World-Leading Human-Care Nurse Leaders for the Future by Brain Korea 21 (BK21) Four Project, College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author: Eunyoung E. Suh Center for World-Leading Human-Care Nurse Leaders for the Future by Brain Korea 21 (BK21) Four Project, College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul National University, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea E-mail: esuh@snu.ac.kr

© 2025 Korean Society of Nursing Science

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) If the original work is properly cited and retained without any modification or reproduction, it can be used and re-distributed in any format and medium.

- 3,402 Views

- 161 Download

Abstract

-

Purpose

- This study aimed to understand the experiences of dialysis and their meaning among patients with chronic kidney disease through a meta-synthesis of the existing literature. Since 2010, the prevalence of end-stage renal disease has doubled in South Korea, which has the sixth-highest incidence worldwide. Although most kidney disease patients undergo dialysis to attenuate disease-related symptoms and prolong their lives, the implications of dialysis on their lives, together with the role played by patients’ significant others, remain underexplored. Similarly, existing research has not considered both patients with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

-

Methods

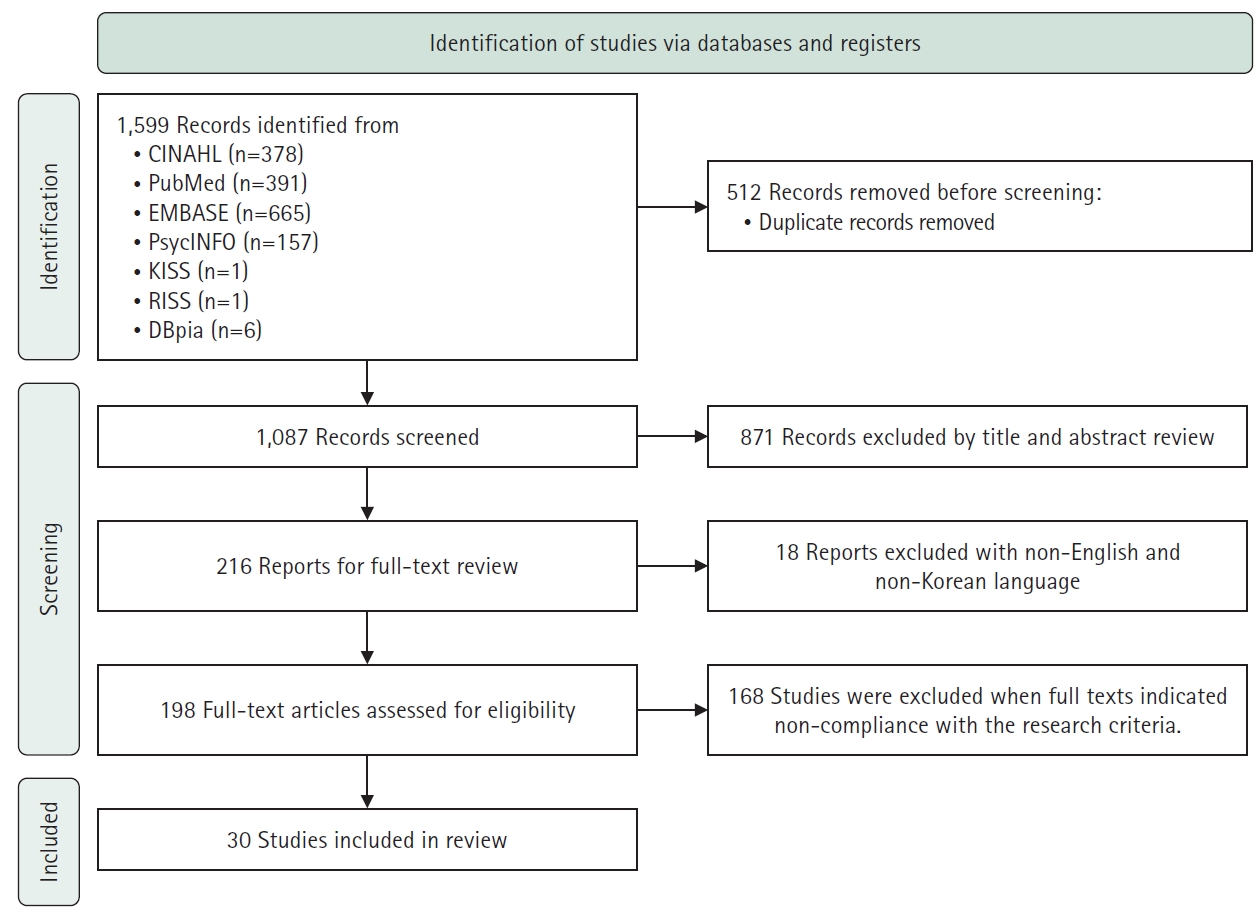

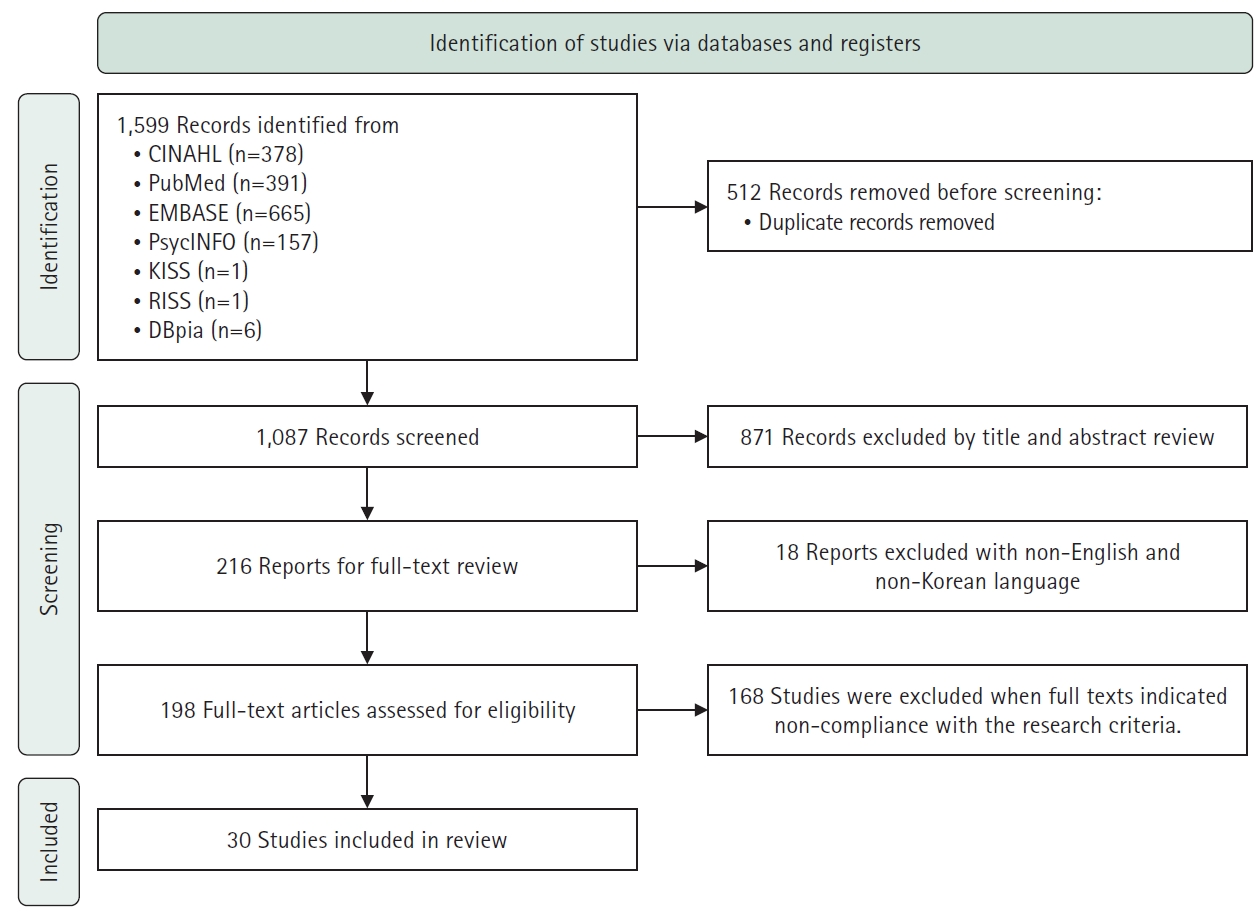

- In this meta-synthesis, seven electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, DBpia, KISS, and RISS) were searched for the terms “dialysis” and “qualitative.” Thirty qualitative studies were selected for examination.

-

Results

- The overriding theme observed in the studies was “I do not have much time left.”–navigating the dual realities of one’s limited existence, while other key themes were: (1) the inevitable experience of the troubles of dialysis, (2) life is extended, but deteriorating in every aspect, (3) accepting dialysis with a positive outlook for life, and (4) essential support experienced in an exhausting life.

-

Conclusion

- These findings are important for the design and delivery of practical and tailored nursing interventions to help patients overcome the various challenges related to dialysis treatment, and improve their quality of life.

Introduction

Methods

Results

1) The inevitable experience of the troubles of dialysis

(1) Facing lifelong hindrances out of nowhere

(2) Spend endless time and energy on dialysis

(3) Living in a shrinking world of isolation

2) Life is extended, but deteriorating in every aspect

(1) The time and energy left are limited

(2) Back and forth of frustration with dialysis

3) Accepting dialysis with a positive outlook for life

(1) Taking dialysis as a part of life through adapting and balancing

(2) Being thankful for living day by day right now

4) Essential support experienced in an exhausting life

(1) Having practical assistance for sustaining health by family and nurses

(2) Living with support, encouragement, and shared emotion by others

Discussion

Conclusion

-

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Acknowledgements

None.

-

Data Sharing Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: SJ, EES. Data curation or/and Analysis: SJ, EES, YS. Funding acquisition: none. Investigation: SJ, EES. Project administration or/and Supervision: SJ, EES. Resources or/and Software: SJ, YS. Validation: SJ, EES. Visualization: SJ, EES. Writing: original draft or/and Review & Editing: SJ, EES, YS. Final approval of the manuscript: SJ, EES, YS.

Article Information

Q1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? Q2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? Q3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? Q4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? Q5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? Q6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? Q7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? Q8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? Q9. Is there a clear statement of findings? Q10. How valuable is the research?

C, can’t tell; N, no; Y, yes.

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2021 [Internet]. CDC; 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://nccd.cdc.gov/CKD/Documents/Chronic-Kidney-Disease-in-the-US-2021-h.pdf

- 2. Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Neal B, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975-1982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9ArticlePubMed

- 3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). 2020 Annual Data Report [Internet]. NIDDK; 2020 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://adr.usrds.org/2020/end-stage-renal-disease

- 4. Hong YA, Ban TH, Kang CY, Hwang SD, Choi SR, Lee H, et al. Trends in epidemiologic characteristics of end-stage renal disease from 2019 Korean Renal Data System (KORDS). Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2021;40(1):52-61. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.20.202ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. The Korean Society of Nephrology. Current renal replacement therapy in Korea [Internet]. The Korean Society of Nephrology; 2020 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ksn.or.kr/bbs/?code=report_eng

- 6. Harwood L, Clark AM. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):109-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.003ArticlePubMed

- 7. Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Eisele G, et al. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):658-666. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.021ArticlePubMed

- 8. Roberts MA, Polkinghorne KR, McDonald SP, Ierino FL. Secular trends in cardiovascular mortality rates of patients receiving dialysis compared with the general population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(1):64-72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.024ArticlePubMed

- 9. Washington T, Zimmerman S, Browne T. Factors associated with chronic kidney disease self-management. Soc Work Public Health. 2016;31(2):58-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2015.1087908ArticlePubMed

- 10. Achempim-Ansong G, Donkor ES. Psychosocial and physical experiences of haemodialysis patients in Ghana. Afr J Nurs Midwifery. 2012;14(1):38-48. https://doi.org/10.25159/2520-5293/9182Article

- 11. Monaro S, Stewart G, Gullick J. A ‘lost life’: coming to terms with haemodialysis. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(21-22):3262-3273. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12577ArticlePubMed

- 12. Yang J, Cho MO. Ethnography on the health life of hemodialysis patients with chronic kidney failure. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2021;33(2):156-168. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2021.33.2.156Article

- 13. Sturesson A, Ziegert K. Prepare the patient for future challenges when facing hemodialysis: nurses’ experiences. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014;9:22952. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.22952ArticlePubMed

- 14. Aghakhani N, Sharif F, Molazem Z, Habibzadeh H. Content analysis and qualitative study of hemodialysis patients, family experience and perceived social support. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(3):e13748. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.13748ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Al Nazly E, Ahmad M, Musil C, Nabolsi M. Hemodialysis stressors and coping strategies among Jordanian patients on hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Nephrol Nurs J. 2013;40(4):321-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.952239

- 16. Raj R, Brown B, Ahuja K, Frandsen M, Jose M. Enabling good outcomes in older adults on dialysis: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-1695-1ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Yang J. An alternative view of living well: survival trajectory of Korean patients with kidney failure on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2017;44(3):219-249. PubMed

- 18. Beng TS, Yun LA, Yi LX, Yan LH, Peng NK, Kun LS, et al. The experiences of suffering of end-stage renal failure patients in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):401-410. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2019.03.04ArticlePubMed

- 19. Elliott BA, Gessert CE, Larson PM, Russ TE. Shifting responses in quality of life: people living with dialysis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1497-1504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0600-9ArticlePubMed

- 20. Calvey D, Mee L. The lived experience of the person dependent on haemodialysis. J Ren Care. 2011;37(4):201-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00235.xArticlePubMed

- 21. Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(2):204-211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.xArticlePubMed

- 22. Paterson BL, Thorne SE, Canam C, Jillings C. Meta-study of qualitative health research: a practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis [Internet]. Sage Publications; 2001 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/meta-study-of-qualitative-health-research/book19552

- 23. Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(10):1342-1365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304269888ArticlePubMed

- 24. Ryu YM, Yu M, Oh S, Lee H, Kim H. Shifting of centricity: qualitative meta synthetic approach on caring experience of family members of patients with dementia. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018;48(5):601-621. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2018.48.5.601ArticlePubMed

- 25. Hatthakit U. Lived experiences of patients on hemodialysis: a meta-synthesis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2012;39(4):295-304. PubMed

- 26. Makaroff KL. Experiences of kidney failure: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2012;39(1):21-29, 80. PubMed

- 27. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer; 2006.

- 28. Ludvigsen MS, Hall EO, Meyer G, Fegran L, Aagaard H, Uhrenfeldt L. Using Sandelowski and Barroso’s meta-synthesis method in advancing qualitative evidence. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(3):320-329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315576493ArticlePubMed

- 29. Crowe M, Gillon D, Jordan J, McCall C. Older peoples’ strategies for coping with chronic non-malignant pain: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;68:40-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.12.009ArticlePubMed

- 30. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [Internet]. CASP; c2018 [cited 2024 Dec 15]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 31. Reid C, Seymour J, Jones C. A thematic synthesis of the experiences of adults living with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(7):1206-1218. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10561015ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Cho MK, Shin G. Gender-based experiences on the survival of chronic renal failure patients under hemodialysis for more than 20 years. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;32:262-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2016.08.008ArticlePubMed

- 33. Krueger L. Experiences of Hmong patients on hemodialysis and the nurses working with them. Nephrol Nurs J. 2009;36(4):379-387. PubMed

- 34. Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW, Wong G, Campbell D, Craig JC. The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(6):873-888. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.045ArticlePubMed

- 35. Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, Lützén K, Clyne N. Maintenance haemodialysis: patients’ experiences of their life situation. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(3):294-300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01036.xArticlePubMed

- 36. Axelsson L, Randers I, Jacobson SH, Klang B. Living with haemodialysis when nearing end of life. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(1):45-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00902.xArticlePubMed

- 37. Karamanidou C, Weinman J, Horne R. A qualitative study of treatment burden among haemodialysis recipients. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(4):556-569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313475898ArticlePubMed

- 38. Lee Si. The problem of the life and death in the existential philosophy. Philos Stud [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2024 Dec 15];75:133-152. Available from: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfView?nodeId=NODE07023323

- 39. Clarkson KA, Robinson K. Life on dialysis: a lived experience. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37(1):29-35. PubMed

- 40. Niu HY, Liu JF. The psychological trajectory from diagnosis to approaching end of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis in China: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(1):29-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.10.006ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Petersson I, Lennerling A. Experiences of living with assisted peritoneal dialysis: a qualitative study. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37(6):605-612. https://doi.org/10.3747/pdi.2017.00045ArticlePubMed

- 42. Ahmad MM, Al Nazly EK. Hemodialysis: stressors and coping strategies. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(4):477-487. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.952239ArticlePubMed

- 43. Rix EF, Barclay L, Stirling J, Tong A, Wilson S. ‘Beats the alternative but it messes up your life’: aboriginal people’s experience of haemodialysis in rural Australia. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005945. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005945ArticlePubMedPMC

- 44. Chiaranai C. The lived experience of patients receiving hemodialysis treatment for end-stage renal disease: a qualitative study. J Nurs Res. 2016;24(2):101-108. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000100ArticlePubMed

- 45. Kontos PC, Miller KL, Brooks D, Jassal SV, Spanjevic L, Devins GM, et al. Factors influencing exercise participation by older adults requiring chronic hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39:1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-007-9265-zArticlePubMed

- 46. Moran A. Experiences of patients on outpatient hemodialysis therapy who are anticipating a transplant. Nephrol Nurs J. 2016;43(3):241-249. PubMed

References

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

| Article no. | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A6 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A7 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | C | Y | Y | Y | 90 |

| A10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A11 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A12 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A13 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A14 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A15 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A16 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A17 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A18 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A19 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A21 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A25 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | C | Y | Y | Y | Y | 95 |

| A29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| A30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 |

| No. | Author (year) | Purpose | Research design | Participants | Age (yr) | Data analysis/data collection | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Achempim-Ansong et al. (2012) | To explore the psychosocial and physical experiences of hemodialysis patients | Explorative descriptive qualitative research | 10 Patients | 20–65 | Content analysis/ | • Psychological experiences (anxiety, depression, anger, worrying, fear of death) |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Social experiences (intentional isolation, inability to attend social functions, effect of dialysis on marriage) | ||||||

| • Economic encounters (difficulty in financing the treatment, loss of income, lowered productivity) | |||||||

| • Physical experiences (problems with sleeping, with fluid and diet restrictions, with accessing the treatment site) | |||||||

| A2 | Axelsson et al. (2012) | To describe and to elucidate the meanings of being severely ill and living with hemodialysis when nearing end of life | Phenomenology | 8 Patients: M (5), F (3) | 66–87 (mean: 78) | Structural analysis/ | • Being subordinate to the deteriorating body |

| Serial qualitative interviews | • Changing outlook on life | ||||||

| • Striving for upheld dignity | |||||||

| A3 | Beng et al. (2019) | To explore the experiences of suffering in end-stage renal failure patients who are on maintenance dialysis | Qualitative study | 19 Patients: M (15), F (4) | 30–60 | Thematic analysis/ | • Physical suffering: physical symptoms, functional limitations |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Psychological suffering: the emotions of suffering, thoughts of suffering | ||||||

| • Social suffering: healthcare-related suffering, burdening of others | |||||||

| • Spiritual suffering: the queries of suffering | |||||||

| A4 | Calvey et al. (2011) | To step into the lives of seven patients once they were outside the dialysis unit | Phenomenology | 7 Patients | 29–60 | Colaizzi’s method/ | Major theme: sense of self |

| In-depth semi-structured interviews | • The future self: an uncertain future, lost dreams, future hopes | ||||||

| • The living self: bodily self, mental self, functional self, social self | |||||||

| • The mortal/fragile self | |||||||

| • The growing/learning self | |||||||

| A5 | Chiaranai (2016) | To better understand the daily life experiences of Thai patients with end-stage renal disease who are on HD | Descriptive phenomenology | 26 Patients: M (8), F (18) | 48–77 | Thematic analysis/ | • Facing life’s limitations: a decrease in physical activity, a narrowed social life, dealing with emotional change such as anger, guilt, depression, unhappiness, spend hidden cost related to HD treatment |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Living with uncertainty: fear of death, do not know future, being scared, feeling insecure that HD treatment will not last for long | ||||||

| • Dependence on medical technology: HD treatment is too important to ignore, feeling save while undergoing HD treatment, HD unit is the familiar place, strictly adhere to HD treatment, cannot live without HD machine | |||||||

| A6 | Cho et al. (2016) | To understand and develop helpful realistic nursing interventions, we interviewed hemodialysis patients of different genders, who have survived more than 20 years, regarding what their survival experiences meant for them. | Phenomenology | 5 Patients: M (3), F (2) | 37–67 (mean: 53) | Colaizzi’s method/ | • Lifelong nasty disease beginning with ‘surely not’ |

| In-depth interviews | • Searching for myself on boundary of life and death | ||||||

| • Fixed ideas regarding gender differences corrected by the power of the family | |||||||

| • Living from survival to hope | |||||||

| A7 | Clarkson et al (2010) | To explore the lived experience of patients with end-stage renal disease | Qualitative study | 10 Patients: M (5), F (5) | 26–85 | Thematic analysis/ | • Lifestyle changes: restricted life, limitations, body/mind/sprit challenges |

| Interview | • Coping: support, family, friends, support group, God, prayer, church | ||||||

| • Areas lacking: health management, education, preparing the next generation | |||||||

| A8 | da Silva Junior et al. (2015) | To recognize the meaning of hemodialysis for patients with chronic renal failure | Descriptive qualitative research | 12 Patients: M (5), F (7) | 24–68 | Symbolic interactionism/ Semi-structured interviews | Central category: dialysis for chronic renal disease carrier |

| • Meaning of hemodialysis | |||||||

| • Experience with the treatment hemodialysis | |||||||

| • The social interactions of patients in | |||||||

| A9 | Hagren et al. (2004) | To examine how patients suffering from chronic kidney disease on maintenance hemodialysis experience their life situation | Qualitative study | 41 Patients: M (26), F (15) | 29–86 (mean: 67.5) | Content analysis/ | • Not finding space for living: struggling with time-consuming care, feeling that life is restricted |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Feeling evoked in the care-situation: sense of emotional distance, feeling vulnerable | ||||||

| • Attempting to maintain manageability of restricted life | |||||||

| A10 | Herlin et al. (2010) | To describe how HD patients, between 30 and 45 years of age, experience their dependence on HD treatment | Phenomenology | 9 Patients: M (5), F (4) | 30–44 (mean: 37) | Giorgi’s method/ | Major theme: the total lack of freedom |

| Semi-structured interviews | • A sense of fear, dependency on caregivers, time lost in dialysis, feelings of loneliness, being on a waiting list for a kidney transplantation | ||||||

| A11 | Jonasson et al. (2017) | To describe changes in life for patients with renal failure undergoing hemodialysis | Qualitative descriptive study | 9 Patients: M (5), F (4) | 41–90 | Content analysis/ | • From liberty to captivity: limitations, dependency |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Adjusting to the new life: to exist during hemodialysis, hope | ||||||

| • The new life moving towards reconciliation: gratitude, acceptance | |||||||

| A12 | Jones et al. (2017) | To obtain UK National Health Service patients’ perspectives on the challenges arising from hemodialysis with the intention of identifying potential improvements | Qualitative study | 20 Patients: M (8), F (12) | 55–88 (mean: 74) | Thematic analysis/ | • Fluctuations in cognitive/physical well-being across the HD cycle |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Restrictions arising from the HD treatment schedule | ||||||

| • Emotional impact of HD on the self and others | |||||||

| A13 | Karamanidou et al. (2014) | To explore the experience of renal patients undergoing dialysis treatment focusing on beliefs about their illness, prescribed treatment, and the challenge of adherence | Phenomenology | 7 Patients: M (3), F (4) | 32–68 | Interpretative phenomenological analysis/ | • Patients have a range of beliefs |

| Semi-structured interviews | about their illness and their treatment consistent with the self-regulatory model of illness, that is, identity, cause, consequences, timeline, and cure. | ||||||

| A14 | Kazemi et al. (2011) | To explore the experiences of social interactions in the daily life of Iranian persons who were receiving hemodialysis | Descriptive, exploratory study | 21 Patients: M (12), F (9) | 24–74 (mean: 45.2) | Thematic analysis/ | • Living with fatigue, changes in self-image, patients’ dependency on the device, place and time of hemodialysis, hiding the disease |

| Semi-structured interviews | |||||||

| A15 | Kim et al. (2017) | To understand the experience of reconstructing life through hemodialysis in chronic renal failure patients and to clarify the meaning of their vivid experience | Phenomenology | 8 Patients: M (4), F (4) | 30–60 | Colaizzi’s method/ | • The beginning of unexpected difficulties |

| Individual in-depth interviews | • Burden of survival brought on by hemodialysis | ||||||

| • The driving force of recovery | |||||||

| • Choices and concentration of today in order | |||||||

| • Everyday life which must be woven sincerely | |||||||

| A16 | Krueger (2009) | To explore Hmong experiences with hemodialysis as well as the experiences of nurses working with these Hmong patients | Qualitative study | 4 Patients: M (4) and 17 nurses: F (17) | NM | Correlation analysis/ | • Overwhelming sadness was the most consistent theme. Sadness resulted physical symptoms of weakness and fatigue, an inability to participate in activities and perform roles and responsibilities; psychosocial symptoms of uncertainty, worthlessness, hopelessness, fear; and the dialysis treatments themselves, as well as the dietary restrictions. |

| Interview | |||||||

| A17 | Lee et al. (2018) | To explain the experiences of patients with renal disease who have just begun hemodialysis in the end-stage | Phenomenology | 8 Patients: M (3), F (5) | 30–60 (mean: 56.8) | Colaizzi’s method/ | • I go into darkness |

| Individual in-depth interviews | • Being disappearing in others | ||||||

| • Baby bird living with love | |||||||

| • Dawn in darkness | |||||||

| • A life longing for the absolute | |||||||

| A18 | Lin et al. (2015) | To examine how people with end-stage renal disease interpret and act upon hemodialysis in their lives | Grounded theory | 15 Patients: M (10), F (5) | 30–78 | Constant comparative analysis/ | Major theme: adopting HD life |

| Individual in-depth interviews | • Slipping into, restricted to a renal word, losing self-control, stuck in an endless process | ||||||

| A19 | Lindsay et al. (2014) | To examine the life experiences of living with chronic illness for the hemodialysis patient | Phenomenology | 7 Patients: M (5), F (2) | 45–81 | Interpretative phenomenological analysis/ | • The challenges of living with chronic renal failure |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Body changes and embodiments | ||||||

| • Illness experience and social relationships | |||||||

| A20 | Monaro et al. (2014) | To describe the essence of the lived experience of patients and families in the early phase of long-term hemodialysis therapy | Phenomenology | 11 Patients: M (5), F (6); 5 family carers | 30–84 (mean: 40.5) | Phenomenological analysis/ | • Lost life: shock and grief, loss of sense of self, loss of spontaneity and personal freedom, changed body feelings, reframing family roles, loss of social connectedness |

| Semi-structured interviews | |||||||

| A21 | Al Nazly et al. (2013) | To examine the lived experiences of Jordanian patients with chronic kidney disease who received hemodialysis | Descriptive phenomenological research | 9 Patients: M (4), F (5) | 20–69 (mean: 47) | Colaizzi’s method/ | • Lifestyle change, time wasted, symptom-related suffering, marital and family role disruption, religious commitment disruption, motivators to alleviate stressors, experience of healthcare providers’ support |

| Semi-structured interviews | |||||||

| A22 | Niu et al. (2017) | To gain insight into the psychological trajectory and life experiences of hemodialysis patients to provide complementary guidance for nurses | Descriptive phenomenological research | 23 Patients: M (15), F (8) | 29–67 | Content analysis/ | • Afraid stage: shock and denying the disease, fear of dialysis, worry about the future, 6-month duration of the afraid stage |

| In-depth interviews | • Adapted stage: compliance, self-pity | ||||||

| • Depression stage: losing interest in life, facing death | |||||||

| A23 | Park et al. (2015) | To explore and understand the adaptation experiences of hemodialysis among women with end-stage renal disease | Grounded theory | 15 Patients: F (15) | 20–70 | Grounded theory method/ | • Four adaptation stages: negative, despair, receptive, and maintenance |

| Individual in-depth interviews | • The causal condition: vague expectations of recovery, refusal to undergo hemodialysis | ||||||

| • The core phenomenon: confinement to the dialysis machine | |||||||

| • The contextual condition: loss of femininity | |||||||

| • The action/interaction strategies: transition with a focus on hemodialysis, pursuit of information on dialysis, learning how to take care of one’s body | |||||||

| • Intervening conditions: support system, controlling one’s mind | |||||||

| • The consequence: having a strong will to live, sustaining one’s life | |||||||

| A24 | Park et al. (2018) | To evaluate the meaning and nature of the experience of dialysis of eight long-term hemodialysis patients with chronic renal failure | Phenomenology | 8 Patients: M (7), F (1) | Mean: 53 | Colaizzi’s method/ | • Beginning of entirely different life: difficult life in receiving hemodialysis, tied to the yoke of dialysis therapy, saying hello to the previous life that ended |

| In-depth interviews | • The life of getting back up again: accepting dialysis, support system, going back to social life | ||||||

| • Life of being present: sharing the experience of dialysis, unavoidable physical limitations, will to live | |||||||

| A25 | Petersson et al. (2017) | To explore adults’ experiences of living with a PD | Qualitative study | 10 Patients: M (6), F (4) | 36–90 (mean: 82.5) | Phenomenological hermeneutical method/ | • Facing new demands: needing dialysis in order to survive, experiencing comorbidities, experiencing limitations |

| In-depth interviews | • Managing daily life: uncertainty about the future, gaining necessary knowledge, autonomy, strategies reducing limitations, recapturing security | ||||||

| • Partnership in care: trust, continuity, person-centeredness | |||||||

| • Experiencing a meaningful life: hopefulness, focusing on life, thankfulness, quality of life | |||||||

| A26 | Raj et al. (2020) | To explore patient perspectives regarding their experience and outcomes with dialysis | Phenomenology | 17 Patients: M (11), F (6) | 70–83 (mean: 76.2) | Thematic analysis/ | • Four domains: the self, the body, effects on daily life and the influences of others |

| Semi-structured interviews | • Four themes: responses to loss (of time, autonomy, previous life), responses to uncertainty (variable symptoms; unpredictable future; dependence on others), acceptance/adaptation (to life on dialysis; to ageing), the role of relationships/support (family, friends, and clinicians) | ||||||

| A27 | Rix et al. (2014) | To describe the experiences of aboriginal people receiving hemodialysis in rural Australia, to inform strategies for improving renal services | Qualitative study | 18 Patients: M (9), F (9) | 30–79 | Strauss’ grounded theory method/ | • The biggest shock of my life |

| In-depth interviews | • Beats the alternative but it messes up your life | ||||||

| • Family is everything | |||||||

| • If I had one of the nurses to help me at home | |||||||

| • Don’t use them big jaw breakers | |||||||

| • Stop them from following us onto the machine | |||||||

| A28 | Sadala et al. (2012) | To highlight the meaning of PD as experienced by patients with chronic renal failure | Qualitative study | 19 Patients: M (8), F (11) | 20–77 (mean: 46) | Phenomenological hermeneutic method/ | • Facing the world of renal failure and dialysis treatment |

| Narrative interviews | • Living changes in one’s own body | ||||||

| • Sources of support | |||||||

| A29 | Sahaf et al. (2017) | To report uncertainty as part of the elderly experiences of living with hemodialysis | Interpretive phenomenology | 9 Patients: M (6), F (3) | 64–88 | Interpretative phenomenological analysis/ | Main theme: uncertainty |

| In-depth unstructured interviews | • Obscure future | ||||||

| • Fear of unknown | |||||||

| • Regularity induced irregularity | |||||||

| A30 | Yang (2017) | To provide guidelines for developing effective nursing interventions by exploring the nursing needs of these patients | Phenomenology | 11 Patients: M (6), F (5) | 30–70 (mean: 51.1) | Giorgi’s method/ | • Emotional engagement: shock, despair, fear, depression, anger, negative assumptions |

| In-depth interviews | • Struggle for survival: changes in their bodies, changes in their time and space, changes in their relationship | ||||||

| • Facing up to the reality: changing their perspectives, increased sense of reality | |||||||

| • Maintaining a hemodialysis-life balance: enduring by regaining a sense of control, suffering from the difficulties of their reality |

| Themes/sub-themes | Studies |

|---|---|

| The inevitable experience of the troubles of dialysis | |

| • Facing lifelong hindrances out of nowhere | A3, A4, A5, A6, A8, A9, A11, A12, A13, A15, A19, A20, A21, A22, A23, A24, A26, A28, A29, A30 |

| • Spend endless time and energy on dialysis | A2, A3, A4, A5, A9, A10, A11, A12, A14, A15, A16, A19, A21 |

| • Living in a shrinking world of isolation | A1, A2, A4, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10, A15, A16, A20, A21, A22, A24, A26, A27, A29 |

| Life is extended, but deteriorating in every aspect | |

| • The time and energy left are limited | A2, A3, A4, A7, A9, A12, A13, A17, A21, A27 |

| • Back and forth of frustration with dialysis | A1, A2, A3, A4, A6, A7, A8, A9, A17, A19, A21, A22, A23, A24, A27, A30 |

| Accepting dialysis with a positive outlook for life | |

| • Taking dialysis as a part of life through adapting and balancing | A3, A7, A9, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A20, A22, A23, A24, A25, A26, A28, A30 |

| • Being thankful for living day by day right now | A2, A6, A7, A11, A13, A15, A22, A24, A25, A27, A30 |

| Essential support experienced in an exhausting life | |

| • Having practical assistance for sustaining health by family and nurses | A4, A6, A7, A8, A17, A19, A21, A23, A24, A28, A30 |

| • Living with support, encouragement, and shared emotion by others. | A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A12, A15, A16, A17, A18, A21, A26, A27, A28, A30 |

| Databases | Search terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ("Renal Dialysis"[MeSH Terms] OR "Dialysis"[MeSH Terms] OR "renal dialys*"[Title/Abstract] OR "hemodialys*"[Title/Abstract] OR "peritoneal dialys*"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("Qualitative Research"[MeSH Terms] OR "qualitative stud*"[Title/Abstract] OR "qualitative research*"[Title/Abstract]) |

| CINAHL | ((TI(dialys* OR hemodialys* OR peritoneal dialys*) OR MH "Dialysis" |

| OR AB(dialys* OR hemodialys* OR peritoneal dialys*)) AND (TI(qualitative stud* OR qualitative research*) OR AB(qualitative stud* OR qualitative research*) OR MH "Qualitative Studies")) | |

| EMBASE | ('dialys*':ti,ab OR 'hemodialys*':ti,ab OR 'peritoneal dialys*':ti,ab) AND |

| ('qualitative stud*':ti,ab OR 'qualitative research*':ti,ab) | |

| PsycINFO | (TI(dialys* OR hemodialys* OR peritoneal dialys*) OR AB(dialys* OR |

| hemodialys* OR peritoneal dialys*)) AND (TI(qualitative stud* OR qualitative research*) OR AB(qualitative stud* OR qualitative research*)) | |

| KISS | All:Dialysis OR hemodialysis OR peritoneal dialysis AND qualitative study |

| RISS | Title:Dialysis OR hemodialysis OR peritoneal dialysis <AND> qualitative study |

| DBpia | All:Dialysis OR hemodialysis OR peritoneal dialysis AND qualitative study |

Q1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? Q2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? Q3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? Q4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? Q5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? Q6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? Q7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? Q8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? Q9. Is there a clear statement of findings? Q10. How valuable is the research? C, can’t tell; N, no; Y, yes.

F, female; HD, hemodialysis; M, male; NM, not mentioned; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Overriding theme: “I do not have much time left.”–navigating the dual realities of one’s limited existence.

CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; DBpia, Database Periodical Information Academic; EMBASE, Excerpta Medica Database; KISS, Korean Studies Information Service System; RISS, Research Information Sharing Service.

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite