Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 55(2); 2025 > Article

-

Research Paper

- The effects of a lifestyle intervention for men in infertile couples in South Korea: a non-randomized controlled trial

-

Yun Mi Kim1

, Ju-Hee Nho2

, Ju-Hee Nho2

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2025;55(2):191-204.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24104

Published online: April 16, 2025

1Department of Nursing, Jesus University, Jeonju, Korea

2College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea

- Corresponding author: Ju-Hee Nho College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Jeonbuk National University, 567 Baekje-daero, Deokjin-gu, Jeonju 54896, Korea E-mail: jhnho@jbnu.ac.kr

- *This manuscript is a condensed version of the first author’s doctoral dissertation from Jeonbuk National University (2023). This work was presented at the 59th Korean Society of Women Health Nursing Conference in 2023, Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

© 2025 Korean Society of Nursing Science

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) If the original work is properly cited and retained without any modification or reproduction, it can be used and re-distributed in any format and medium.

- 3,652 Views

- 139 Download

- 1 Crossref

Abstract

-

Purpose

- This study aimed to evaluate the effects of an interaction model of client health behavior (IMCHB)-based lifestyle intervention on health-promoting behaviors, infertility stress, fertility-related quality of life, and semen quality in men in infertile couples.

-

Methods

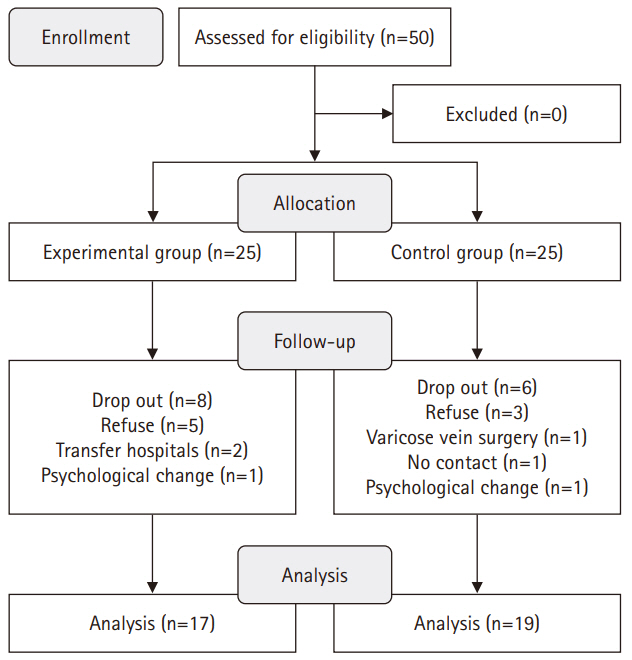

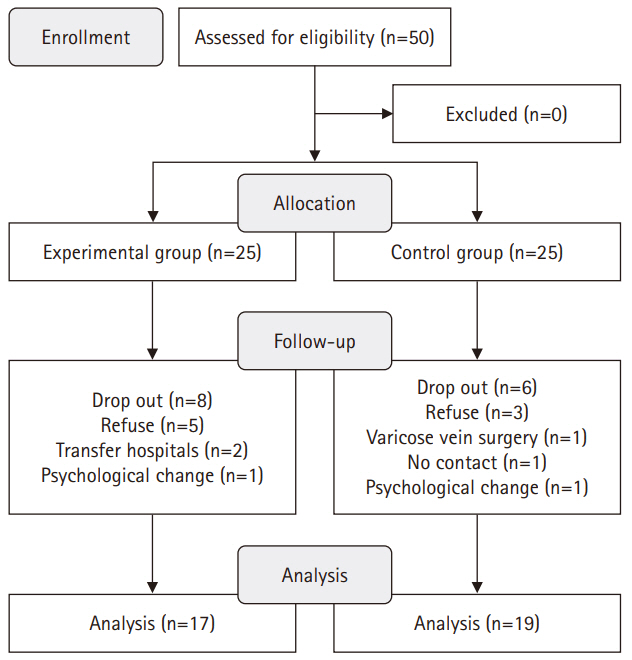

- This study used a quasi-experimental, non-equivalent control group, pretest-posttest design, with participants divided into an experimental group (n=17) and a control group (n=19). The 16-session, 8-week intervention included components such as reproductive health education, physical activity, nutritional management, and stress management. Data collection occurred between July 1, 2021 and September 27, 2022. The outcomes measured included health-promoting behaviors, infertility stress, fertility-related quality of life, and sperm quality (volume, total motility, immobility, concentration, and normal morphology).

-

Results

- The experimental group showed significant improvements in health-promoting behaviors (z=–2.27, p=.023) and reductions in infertility stress (t=–2.40, p=.022) compared to the control group. Total sperm motility (F=4.39, p=.045) and normal morphology (z=2.86, p=.017) were also significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group.

-

Conclusion

- The IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention significantly increased health-promoting behaviors, reduced infertility stress, and improved key sperm parameters, indicating its effectiveness in supporting the reproductive health of men in infertile couples.

Introduction

H1. The experimental group receiving an IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention would reveal greater improvement in HPB than the control group.

H2. The experimental group receiving an IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention would exhibit lower infertility stress than the control group.

H3. The experimental group receiving an IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention would demonstrate greater improvements in fertility-related quality of life than the control group.

H4. The experimental group receiving an IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention would demonstrate better sperm quality (volume, total motility, immobility, concentration, and normal morphology) than the control group.

Methods

1) Health-promoting behaviors

2) Infertility stress

3) Fertility-related quality of life

4) Sperm quality

• Sperm volume: ≥1.5 mL, measured using a sterilized syringe.

• Total motility: ≥40%, including both progressive and non-progressive motility.

• Immobility: Percentage of non-moving sperm.

• Concentration: ≥15 million sperm/mL.

• Normal morphology: ≥4%, indicating sperm with normal size, shape, and structure. Abnormalities in sperm morphology, such as those in the head, mid piece, or tail, can reduce reproductive capacity.

1) Participant assignment

2) Pre-test

3) IMCHB-based lifestyle intervention

4) Routine care

5) Post-test

Results

1) Hypothesis 1

2) Hypothesis 2

3) Hypothesis 3

4) Hypothesis 4

Discussion

Conclusion

-

Conflicts of Interest

Ju-Hee Nho has been the editorial board member of JKAN since 2024 but has no role in the review process. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Acknowledgements

None.

-

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (No., NRF-2020R1F1A1050767).

-

Data Sharing Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: YMK, JHN. Data curation or/and Analysis: YMK, JHN. Funding acquisition: JHN. Investigation: JHN. Project administration or/and Supervision: JHN. Resources or/and Software: YMK, JHN. Validation: YMK, JHN. Visualization: YMK, JHN. Writing: original draft or/and Review & Editing: YMK, JHN. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Article Information

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or mean±standard deviation.

Cont., control group; Exp., experimental group; IMCHB, interaction model of client health behavior.

a)By Mann-Whitney U test. b)By independent t-test. c)By ranked analysis of covariance (covariate: pre-test score of total motility and immobility).

- 1. Punab M, Poolamets O, Paju P, Vihljajev V, Pomm K, Ladva R, et al. Causes of male infertility: a 9-year prospective monocentre study on 1737 patients with reduced total sperm counts. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(1):18-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew284ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. World Health Organization. Infertility [Internet]. WHO; 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility

- 3. Kamel RM. Management of the infertile couple: an evidence-based protocol. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-8-21ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Joja OD, Dinu D, Paun D. Psychological aspects of male infertility: an overview. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;187:359-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.067Article

- 5. Warchol-Biedermann K. The etiology of infertility affects fertility quality of life of males undergoing fertility workup and treatment. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15(2):1557988320982167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320982167ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Greil AL, Slauson-Blevins K, McQuillan J. The experience of infertility: a review of recent literature. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32(1):140-162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01213.xArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Onat G, Kizilkaya Beji N. Effects of infertility on gender differences in marital relationship and quality of life: a case-control study of Turkish couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(2):243-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.033ArticlePubMed

- 8. Dong M, Wu S, Zhang X, Zhao N, Tao Y, Tan J. Impact of infertility duration on male sexual function and mental health. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022;39(8):1861-1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-022-02550-9ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Chen Z, Hong Z, Wang S, Qiu J, Wang Q, Zeng Y, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical intervention on sperm quality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 2023;15(10):4253-4268. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204727ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Mikkelsen AT, Madsen SA, Humaidan P. Psychological aspects of male fertility treatment. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(9):1977-1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12058ArticlePubMed

- 11. Durairajanayagam D. Lifestyle causes of male infertility. Arab J Urol. 2018;16(1):10-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aju.2017.12.004ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Mindlis I, et al. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(6):646-659. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx022ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Kaltsas A, Zachariou A, Dimitriadis F, Chrisofos M, Sofikitis N. Empirical treatments for male infertility: a focus on lifestyle modifications and medicines. Diseases. 2024;12(9):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12090209ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Foucaut AM, Faure C, Julia C, Czernichow S, Levy R, Dupont C, et al. Sedentary behavior, physical inactivity and body composition in relation to idiopathic infertility among men and women. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0210770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210770ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Rosety MÁ, Díaz AJ, Rosety JM, Pery MT, Brenes-Martín F, Bernardi M, et al. Exercise improved semen quality and reproductive hormone levels in sedentary obese adults. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34(3):603-607. https://doi.org/10.20960/nh.549ArticlePubMed

- 16. Dupont C, Aegerter P, Foucaut AM, Reyre A, Lhuissier FJ, Bourgain M, et al. Effectiveness of a therapeutic multiple-lifestyle intervention taking into account the periconceptional environment in the management of infertile couples: study design of a randomized controlled trial - the PEPCI study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):322. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2855-9ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Masoumi SZ, Khani S, Kazemi F, Kalhori F, Ebrahimi R, Roshanaei G. Effect of marital relationship enrichment program on marital satisfaction, marital intimacy, and sexual satisfaction of infertile couples. Int J Fertil Steril. 2017;11(3):197-204. https://doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2017.4885ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Lee M, Lee H, Kim Y, Kim J, Cho M, Jang J, et al. Mobile app-based health promotion programs: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2838. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122838ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Qureshi FM, Golan R, Ghomeshi A, Ramasamy R. An update on the use of wearable devices in men’s health. World J Mens Health. 2023;41(4):785-795. https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.220205ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Cox CL. An interaction model of client health behavior: theoretical prescription for nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1982;5(1):41-56. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198210000-00007ArticlePubMed

- 21. Kim M. National policies for infertility support and nursing strategies for patients affected by infertility in South Korea. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2021;27(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2021.03.12.1ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Lee HK, Park YS. Effects of a health promotion program on college students who are on the brink of dyslipidemia, based on Cox’s interaction model. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2014;15(5):3058-3068. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2014.15.5.3058Article

- 23. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149-1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149ArticlePubMed

- 24. Wang C, Mbizvo M, Festin MP, Björndahl L, Toskin I; other Editorial Board Members of the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. Evolution of the WHO “Semen” processing manual from the first (1980) to the sixth edition (2021). Fertil Steril. 2022;117(2):237-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.11.037ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987;36(2):76-81. PubMed

- 26. Hwang WJ, Hong OS, Rankin SH. Predictors of health-promoting behavior associated with cardiovascular diseases among Korean blue-collar workers. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP691-NP702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539513500338ArticlePubMed

- 27. Newton CR, Sherrard W, Glavac I. The Fertility Problem Inventory: measuring perceived infertility-related stress. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(1):54-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00164-8ArticlePubMed

- 28. Kim JH, Shin HS. A structural model for quality of life of infertile women. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2013;43(3):312-320. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.312ArticlePubMed

- 29. Boivin J, Takefman J, Braverman A. The Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) tool: development and general psychometric properties. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):409-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.046ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Ngai FW, Loke AY. Relationships between infertility-related stress, family sense of coherence and quality of life of couples with infertility. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2022;25(3):540-547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647273.2021.1871781ArticlePubMed

- 31. Kim YM, Nho JH. Factors influencing infertility-related quality of life in infertile women. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2020;26(1):49-60. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2020.03.08ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Boitrelle F, Shah R, Saleh R, Henkel R, Kandil H, Chung E, et al. The sixth edition of the WHO manual for human semen analysis: a critical review and SWOT analysis. Life (Basel). 2021;11(12):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11121368ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. World Health Organization. WHO guideline on school health services [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030787

- 34. Nho JH, Hwang ES. Effects of multidisciplinary lifestyle modification program on health-promoting behavior, psychological distress, body composition and reproductive symptoms among overweight and obese middle-aged women. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2019;31(6):663-676. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2019.31.6.663Article

- 35. Bisht S, Banu S, Srivastava S, Pathak RU, Kumar R, Dada R, et al. Sperm methylome alterations following yoga-based lifestyle intervention in patients of primary male infertility: a pilot study. Andrologia. 2020;52(4):e13551. https://doi.org/10.1111/and.13551ArticlePubMed

- 36. Rafiee B, Morowvat MH, Rahimi-Ghalati N. Comparing the effectiveness of dietary vitamin C and exercise interventions on fertility parameters in normal obese men. Urol J. 2016;13(2):2635-2639. https://doi.org/10.22037/uj.v13i2.3279ArticlePubMed

- 37. Cho YH, Hwang YS, Oh SI. The effects of aerobic exercise for 8 weeks on the body composition, blood lipid and liver enzyme of obese women. J Sport Leisure Stud. 2009;38(2):755-764. https://doi.org/10.51979/KSSLS.2009.11.38.755Article

- 38. King HA, Jeffreys AS, McVay MA, Coffman CJ, Voils CI. Spouse health behavior outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a spouse-assisted lifestyle change intervention to improve patient low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Behav Med. 2014;37:1102-1107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9559-4ArticlePubMed

- 39. Steegers-Theunissen R, Hoek A, Groen H, Bos A, van den Dool G, Schoonenberg M, et al. Pre-conception interventions for subfertile couples undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment: modeling analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(11):e19570. https://doi.org/10.2196/19570ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Xiaomi. Smart Band X. 8 active [Internet]. Xiaomi; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.mi.com/kr/product/xiaomi-smart-band-8-active/

- 41. East Tennessee State University. ACSM’s general exercise guidelines [Internet]. East Tennessee State University; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.etsu.edu/exercise-is-medicine/guidelines.php

- 42. Gustafsson SR, Wahlberg AC. The telephone nursing dialogue process: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):345. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01509-0ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Mattisson M, Börjeson S, Årestedt K, Lindberg M. Interaction between telenurses and callers: a deductive analysis of content and timing in telephone nursing calls. Patient Educ Couns. 2024;123:108178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2024.108178ArticlePubMed

- 44. Jayasena CN, Sharma A, Abbara A, Luo R, White CJ, Hoskin SG, et al. Burdens and awareness of adverse self-reported lifestyle factors in men with sub-fertility: a cross-sectional study in 1149 men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020;93(3):312-321. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14213ArticlePubMed

- 45. Gollenberg AL, Liu F, Brazil C, Drobnis EZ, Guzick D, Overstreet JW, et al. Semen quality in fertile men in relation to psychosocial stress. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1104-1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.018ArticlePubMed

- 46. Dhawan V, Kumar M, Deka D, Malhotra N, Dadhwal V, Singh N, et al. Meditation & yoga: impact on oxidative DNA damage & dysregulated sperm transcripts in male partners of couples with recurrent pregnancy loss. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(Suppl):S134-S139. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1988_17ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Psychological Stress and Male Infertility: Oxidative Stress as the Common Downstream Pathway

Aris Kaltsas, Stamatis Papaharitou, Fotios Dimitriadis, Michael Chrisofos, Nikolaos Sofikitis

Biomedicines.2026; 14(2): 259. CrossRef

Fig. 1.

| Session: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 (every Tuesday for 8 weeks) | Session: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 (every Friday for 8 weeks) | Session: daily | Elements of client professional interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Method | Feedback | Method | Monitoring | Method | |

| Reproductive health education | Digital short message service | Consultation | Telephone | Self-checking | Wearable device | Client professional interaction |

| - Reproductive health for men and women | - Individualized feedback | - Assessing the lifestyle patterns via lifestyle checklist | Uniform resource locator | - Text messages | ||

| - Lifestyle factors affecting fertility | - Recommendations on optimizing their physical activity, dietary habits, and stress management strategies. | - Monitoring | ||||

| - Lifestyle modification strategies for optimizing reproductive outcomes | - Telephone consultations and monitoring | |||||

| Physical activity management | - Assessment of exercise, diet, and stress status | |||||

| - Intensity and method of walking | Health information | |||||

| - Methods of strength training and aerobic exercise | - Education and information | |||||

| - Precautions during physical activity | - Knowledge reinforcement | |||||

| - How to use a smart band and a physical activity diary | Professional/technical competencies | |||||

| Nutritional management | - Telephone and individual counseling | |||||

| - Men’s healthy diet and nutrition education | - Decisional control: phone calls and mobile messages | |||||

| - Nutrition label confirmation | Affective support | |||||

| - Nutritional education related to reproductive health | - Praise | |||||

| - 24-hour dietary recall | - Encouragement | |||||

| Stress management | - Support | |||||

| - Relaxation and mindfulness techniques (meditation, bedtime relaxation) | ||||||

| - Talking with one’s spouse (before going to bed, taking a walk) | ||||||

| - Sufficient sleep (about 7 hours) | ||||||

| - Light walking with one’s spouse | ||||||

| Characteristic | Exp. (n=17) | Cont. (n=19) | χ2 or t or z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)/M±SD/med (IQR) | ||||

| Age (yr) | 0.15 | .881 | ||

| ≤30 | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 31–34 | 5 (29.4) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| 35–40 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| ≥41 | 6 (35.3) | 6 (31.6) | ||

| Mean±SD | 37.24±4.76 | 38.00±5.16 | ||

| Age of spouse (yr) | 0.99 | .804 | ||

| ≤30 | 3 (17.7) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| 31–34 | 5 (29.4) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| 35–40 | 4 (23.5) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| ≥41 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| Mean±SD | 34.94±4.48 | 35.42±4.49 | ||

| Marriage duration (mo) | 5.55 | .136 | ||

| ≤24 | 3 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| 25–36 | 5 (29.4) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| 37–48 | 4 (23.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| ≥49 | 5 (29.4) | 9 (47.4) | ||

| Mean±SD | 49.18±35.91 | 53.89±36.18 | ||

| Religion | 1.99 | .192 | ||

| Yes | 12 (70.6) | 9 (47.4) | ||

| No | 5 (29.4) | 10 (52.6) | ||

| Education | 0.96 | .434 | ||

| ≤High school | 5 (29.4) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| ≥University | 12 (70.6) | 16 (84.2) | ||

| Chronic disease | 0.01 | >.999 | ||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| No | 16 (94.1) | 18 (94.7) | ||

| Monthly individual income (10,000 KRW) | 1.14 | .887 | ||

| <200 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| 200–299 | 5 (29.4) | 6 (31.6) | ||

| 300–399 | 3 (17.7) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| 400–499 | 4 (23.5) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| ≥500 | 4 (23.5) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.63 | .502 | ||

| Yes | 12 (70.6) | 11 (57.9) | ||

| No | 5 (29.4) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Smoking | 0.39 | .695 | ||

| Yes | 3 (17.7) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| No | 14 (82.3) | 14 (73.7) | ||

| Physical activity | 0.01 | >.999 | ||

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| No | 11 (64.7) | 12 (63.2) | ||

| Sleeping hours (hr) | 2.73 | .158 | ||

| <3 | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 3–5 | 7 (41.2) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| 6–7 | 7 (41.2) | 14 (73.7) | ||

| ≥8 | 2 (11.7) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.07±3.39 | 25.40±3.11 | 0.62 | .540 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 8 (47.1) | 6 (35.3) | ||

| Overweight (18.5–24.9) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | 1.12 | .570 |

| Obesity (≥30.0) | 4 (23.5) | 5 (29.4) | ||

| Semen analysis experience | 0.39 | .736 | ||

| Yes | 8 (47.1) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| No | 9 (52.9) | 12 (63.2) | ||

| Health-promoting behaviors | 117.00 (IQR, 109.00) | 113.00 (IQR, 104.00) | –0.65a) | .516 |

| Infertility stress | 166.00±19.98 | 149.58±27.55 | 2.03 | .051 |

| Fertility-related quality of life | 72.37±11.47 | 70.27±10.89 | 0.56 | .577 |

| Volume (mL) (n=30) | 4.00 (IQR, 3.00) | 3.50 (IQR, 2.75) | –0.49a) | .626 |

| Total motility (%) (n=30) | 64.98 (IQR, 41.39) | 83.84 (IQR, 76.33) | –2.03a) | .042 |

| Immobility (%) (n=30) | 35.02 (IQR, 13.60) | 16.16 (IQR< 8.86) | 2.97a) | .007 |

| Concentration (million/mL) (n=30) | 25.53 (IQR, 13.26) | 36.40 (IQR, 21.25) | –1.57a) | .117 |

| Normal morphology (%) (n=30) | 9.98 (IQR, 8.12) | 19.76 (IQR, 11.74) | –1.47a) | .143 |

| Variable | Pre-test | Post-test | Difference | z or t or F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Med (IQR)/M±SD | |||||

| Health promoting behaviors | –2.27a) | .023 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 117.00 (109.00) | 132.00 (125.00) | 8.00 (1.00) | ||

| Cont. (n=19) | 113.00 (104.00) | 119.00 (104.00) | –1.00 (–5.00) | ||

| Infertility stress | –2.40b) | .022 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 166.00±19.98 | 114.53±22.59 | –51.47±34.35 | ||

| Cont. (n=19) | 149.58±27.55 | 126.79±26.00 | –22.79±37.18 | ||

| Fertility-related quality of life | 0.63b) | .531 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 72.37±11.47 | 74.12±6.88 | 1.76±10.08 | ||

| Cont. (n=19) | 70.26±10.89 | 69.70±11.74 | –0.57±11.74 | ||

| Volume (mL) (n=30) | –0.49a) | .626 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 4.00 (3.00) | 4.00 (4.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | ||

| Cont. (n=13) | 3.50 (2.75) | 3.00 (2.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | ||

| Total motility (%) (n=30) | 4.39c) | .045 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 64.98 (41.39) | 86.09 (72.83) | 16.33 (1.67) | ||

| Cont. (n=13) | 83.84 (76.33) | 90.43 (70.24) | 0.00 (–8.74) | ||

| Immobility (%) (n=30) | 2.04c) | .164 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 35.02 (13.60) | 13.92 (10.98) | –16.33 (–31.45) | ||

| Cont. (n=13) | 16.16 (8.86) | 9.57 (6.40) | –0.61 (–8.54) | ||

| Concentration (million/mL) (n=30) | –1.57a) | .117 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 25.53 (13.26) | 34.41 (17.67) | 3.92 (–4.44) | ||

| Cont. (n=13) | 36.40 (21.25) | 51.11 (21.79) | 2.03 (–6.80) | ||

| Normal morphology (%) (n=30) | 2.86a) | .017 | |||

| Exp. (n=17) | 9.98 (8.12) | 23.55 (9.91) | 2.52 (0.02) | ||

| Cont. (n=13) | 19.76 (11.74) | 17.48 (9.95) | –0.23 (–10.24) | ||

IMCHB, interaction model of client health behavior.

Values are presented as number (%), mean±SD, or median (IQR). Cont., control group; Exp., experimental group; IQR, interquartile range; KRW, Korean won; SD, standard deviation. By Mann-Whitney U test.

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or mean±standard deviation. Cont., control group; Exp., experimental group; IMCHB, interaction model of client health behavior. a)By Mann-Whitney U test. b)By independent t-test. c)By ranked analysis of covariance (covariate: pre-test score of total motility and immobility).

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite