Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 50(6); 2020 > Article

- Research Paper Motives for Empathy among Clinical Nurses in China: A Qualitative Study

- Yu Zhu, Ming-Mei He, Ji-Min Zhu, Li Huang, Bai-Kun Li

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2020;50(6):778-786.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.20123

Published online: December 31, 2020

2Obstetrics Department, Anhui Women and Child Health Care Hospital, Hefei, China

3School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, Hefei, China

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore the motives of clinical nurses for experiencing empathy with patients and their families based on a self-determination theory framework.

Methods

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews with twenty-one nurses at four tertiary hospitals in Anhui, China, were conducted, recorded and transcribed. A content analysis with a directed approach was performed.

Results

An analysis of the interview transcripts revealed three categories of empathy motivation: autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and a lack of empathy motivation. Autonomous motivation included personal interests, enjoyment and a sense of value, pure altruism, assimilation, and recognition of the importance of empathy. Controlled motivation highlighted pressures from oneself and others, the possibility of tangible or intangible rewards, and avoidance of adverse effects. Finally, a lack of empathy motivation referred to a lack of intention for empathy and denial of the value of empathy.

Conclusion

This study provides a deep understanding of the motives underlying empathy in nurses. The results reveal the reasons for empathy and may support the development of effective strategies to foster and promote empathy in nurses.

Published online Dec 31, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.20123

Motives for Empathy among Clinical Nurses in China: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore the motives of clinical nurses for experiencing empathy with patients and their families based on a self-determination theory framework.

Methods

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews with twenty-one nurses at four tertiary hospitals in Anhui, China, were conducted, recorded and transcribed. A content analysis with a directed approach was performed.

Results

An analysis of the interview transcripts revealed three categories of empathy motivation: autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and a lack of empathy motivation. Autonomous motivation included personal interests, enjoyment and a sense of value, pure altruism, assimilation, and recognition of the importance of empathy. Controlled motivation highlighted pressures from oneself and others, the possibility of tangible or intangible rewards, and avoidance of adverse effects. Finally, a lack of empathy motivation referred to a lack of intention for empathy and denial of the value of empathy.

Conclusion

This study provides a deep understanding of the motives underlying empathy in nurses. The results reveal the reasons for empathy and may support the development of effective strategies to foster and promote empathy in nurses.

INTRODUCTION

Empathy is multidimensional concept, contains different components, and has different definitions [1, 2, 3, 4]. Most scholars focus on three dimensions of empathy, i.e., cognitive component, emotional component and behavioural component, and agree that empathy includes the ability to feel the experiences of others (e.g., patients) (emotional component), an understanding of these experiences from an objective perspective (cognitive component), and a capacity to convey this understanding (behavioural component) [3, 4].

Showing empathy to patients is a principal aspect of health care providers' communication skills [5] and allows nurses to appropriately respond to the needs of patients and their families [6]. Thus, empathy improves the nurse-patient relationship and patient compliance and leads to better management of patient problems, thus promoting patient rehabilitation [7, 8, 9]. Kesbakhi & Rohani [10] indicated that the motivation for empathetic communication should be promoted to improve patients' satisfaction and quality of life. Thus, understanding how empathy is motivated in nurses should be further investigated and could have practical implications for developing empathy-based care.

Motives are intended to propel or cause action and can explain why people choose a specific behaviour [3]. American psychologists Deci & Ryan [11] and Ryan & Deci [12] suggested that motivation is a continuum from nonmotivation to extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. Based on the degree of individual autonomy, the researchers [11, 12] further identified three motivational subsystems within the widely used self-determination theory, i.e., autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and amotivation. Among them, autonomous motivation is associated with better outcomes and considered as the desirable type of motivation [13]. We hypothesize that nurses can experience autonomous motivation and controlled motivation when empathizing with a patient or may even lack empathy motivation for a variety of reasons.

However, research has little explored clinical nurses' empathy motivations in daily working practices worldwide. Thus, in-depth research on nurses' experience of empathy motivation in nursing care has clinical significance. Munhall [14] noted that a qualitative approach is more suitable for identifying hidden or less-recognized perceptions. Therefore, the experiences of nurses' empathetic motivations should be investigated through a qualitative research method.

The present study aims to explore Chinese nurses' experiences with empathy motivation based on the theoretical framework of self-determination theory. This study is part of a larger project (the Conceptual Framework and Evaluation Tool of Nurses' Nurse-Patient Empathy Motivation at Hospitals in China) on the perceptions of empathy by clinical nurses and the tools used to evaluate nurses' empathy motivation.

METHODS

1. Study design

The study design was a qualitative study using content analysis method with semi-structured interviews.

2. Setting and samples

Nurses working in clinical units were non-randomly sampled from four hospitals in China from September to December 2016. The inclusion criteria were as follows: good level of spoken Chinese worked as a nurse for at least one year, and volunteered for the study.

The exclusion criteria were advanced nurses from other hospitals, nurses on leave, and nurses working in supply rooms, endoscopy centres or other nonclinical departments.

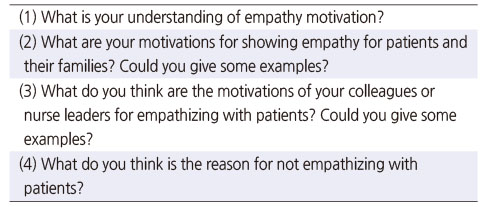

3. Data collection

Before the interviews, semi-structured interview questions were developed based on a review of the literature and the self-determination theory, which is widely used in organizational management, education, sports and psychological counselling and other fields [11, 12]. Then, the interview questions were discussed by the research team, which consisted of staff from nurse management, nursing education, psychology and clinical nursing. Finally, the interview questions were formed (Table 1).

Table 1

Final Interview Questions

Interview times were arranged with the nurses by phone or text message. To ensure a quiet environment and no interference from others, the interviews were conducted in offices or lounges. Each interview lasted 30 to 40 minutes. We found that saturation occurred at the 21st interview as no new information appeared.

Before the interviews, the researcher asked the nurses what they knew about empathy and reviewed their basic understanding of empathy to ensure the accuracy of the interview data. One interviewer has a master's degree, psychology knowledge, qualitative research experience and two years of systematic interpersonal skills training. The other interviewer is a senior nurse working as a clinical teaching instructor in a maternity ward. The interviewers established a relationship with most of the participants before the study.

4. Data analysis

The content analysis method, which is widely used in health studies [15], was applied with a directed approach in which the texts were scrutinized and categorized according to the self-determination theory [11, 12]. Following the content analysis procedures, two female interviewers listened to the recordings carefully, transcribed them word for word within 24 hours after each interview and summarized the nonverbal information and the interview environment. Then, the two researchers independently coded the data under the guidance of a professor with a psychological research foundation and qualitative research experience. Interactive discussions were conducted to reach consensus in case of inconsistency [15]. Furthermore, the researchers considered contextual factors while analysing the interview data with an active analytic stance, and two cases were randomly selected by the professor to verify the analysis results and further improve the reliability and validity of the analysis results for the interview data [16, 17].

5. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (NO. 2018AH-WY012). Before the clinical nurses were recruited, permission from the department at each hospital was obtained. Comprehensive verbal information stating the purpose, voluntary participation, anonymity and confidentiality of the study was provided to the nurses. Verbal approval from the participants regarding audio recording of the interviews was obtained.

RESULTS

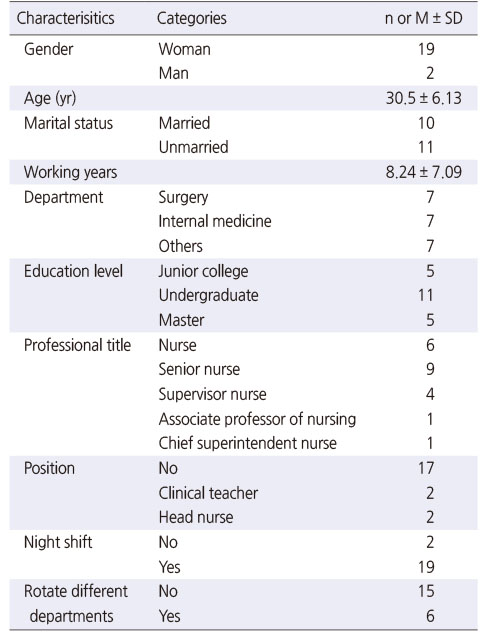

1. Characteristics of the participants

Twenty-one participants were interviewed, and their mean age was 30.5 years old (19 women and 2 men) and mean number of working years was 8.24 (Table 2).

Table 2

Participant's Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics (N = 21)

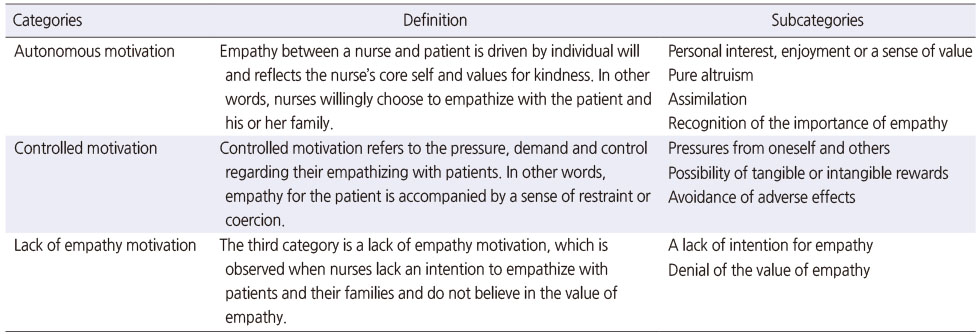

The following three categories were defined based on the data: autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and a lack of empathy motivation. Table 3 presents the categories and subcategories based on our analysis.

Table 3

Categories and Subcategories Derived from the Semi-Structured Interviews

1) Category 1: Autonomous motivation

Empathy between a nurse and patient is driven by individual will and reflects the nurse's core self and values for kindness. In other words, nurses willingly choose to empathize with the patient and his or her family.

(1) Subcategory 1: Personal interest, enjoyment or a sense of value

Nurses can be autonomously motivated when their empathy is guided by personal interest, enjoyment or a sense of value of the empathy. Seven nurses showed empathy due to their own inner interests or enjoyment.

I had a patient who had been hospitalized repeatedly for 14 years … I came and took her hand, and she had tears in the corners of her eyes (crying). The patient can feel our empathy, and our empathy will make them less fearful. I like to contact and help patients, which makes me feel good about life (Nurse 1).

Sometimes when we're doing vaginal irrigation, they're shy and their muscles are tense. There's no way to perform the procedure … Indirectly conveying their understanding and letting them know that we know that they are nervous. When patients say “You're really nice,” I'm happy (Nurse 18).

Some introverted patients are quiet on the surface before surgery, although if you take their blood pressure, it may be high despite a lack of hypertension; then, you know they are nervous. If you soothe the patient, you'll feel good (Nurse 9).

In addition to this, a sense of value also promotes nurses' empathy towards patients and their families.

Many patients don't understand their disease and what to pay attention to; we know more, and talking to him (the patient) will generate a sense of value (laugh) (Nurse 18).

You will find that nursing work is not just performing injections and delivering drugs… (Nurses) derive a sense of achievement (firm attitude, staring at me, nodding) (Nurse 5).

(2) Subcategory 2: Pure altruism

Some nurses also empathize with patients with the intention of improving patients' situations without asking for anything in return. Thus, love and a sense of devotion motivate the tireless empathy that these nurses have for the patient and their family.

As they say, people are naturally good, and the sick themselves are a vulnerable group. Wanting to understand the patient and express their understanding, these are the most basic things (Nurse 8).

When the patient shows pain but still carries it on his own, I always want to comfort him or talk to him to alleviate his pain (Nurse 13).

You may not believe it. I have a strong spirit of dedication to performing something good for society, for the patients; simply put, this is the way (Nurse 10).

(3) Subcategory 3: Assimilation

Nurses assimilate the values of the outside world and progressively transform them into their own values. In other words, empathy becomes integrated into the nurses' sense of self. Some nurses indicated that empathizing with the patient is consistent with their own values.

Always believing that all the patient's statements are from the heart and that they have needs. This is the value of life, to do meaningful things to help patients (Nurse 1).

The hospital has this saying – that everything is patient-centred. I feel this has been deeply instilled; this is a special aspect of this profession (Nurse 15).

(4) Subcategory 4: Recognition of the importance of empathy

Nurses were motivated to empathize with patients because they fully recognize of the importance of showing empathy to the patient. This phenomenon is very common in clinical nursing work. Eight nurses mentioned that showing empathy maintains, alleviates or promotes the nurse-patient relationship.

There is a need for a harmonious doctor-patient relationship, a very harmonious relationship with patients, building trust, and forming a very good cultural atmosphere in the department (Nurse 11).

He will come to you if he has anything he needs help with in the future. (We) greet each other when we meet (in the department). I think that we do have a good relationship. He doesn't ignore you when you talk to him … Isn't that what we work for (Nurse 2).

In addition, providing empathetic care could improve patient compliance and mental burden, thereby facilitating health care work and ultimately facilitating patient recovery. Twelve nurses believed that these aspects encouraged them to be as empathetic as possible with their patients.

This is a psychological comfort to the patient, helping the patient and family to get more emotional support and information, reducing fear, and helping patients solve the difficulties and problems they want to resolve (Nurse 17).

For example, patients with oesophageal cancer can't eat rice or even swallow saliva in the later stage. They are especially depressed and even desperate. If you tell them some examples of success, or some care in life, even a word or two, they will be very grateful afterwards. Even if what you tell them (the patient) has not changed anything, it is enough to increase their confidence and keep going (Nurse 12).

We have empathy with the patient and he must also have feelings. Natural compliance will be better and more compatible with treatment and care as well, so it is more convenient to carry out work (Nurse 20).

Moreover, nurses can learn from empathizing with patients, which contributes to their own professional growth and self-improvement. These improvements motivate nurses to continue to provide empathetic care for patients, forming a virtuous circle.

Empathizing with your patients can help improve your nursing performance. It is also a process of learning. If you have seen a lot, you will know who the person may be, what ideas they may have and how we should deal with them. Because the work is predictable, you can better understand the patient progression (Nurse 12).

Learn how to make yourself better through other people's stories. If you can empathize with a stranger in the ward … why can't you treat your family better? After all, work is just a part of your life (Nurse 10).

2) Category 2: Controlled motivation

Controlled motivation refers to the pressure, demand and control on their empathizing with patients. In other words, empathy for the patient is accompanied by a sense of restraint or coercion.

(1) Subcategory 1: Pressures from oneself and others

Empathizing with patients is an expectation and requirement of society for the nursing profession because of the impression others have, and it naturally becomes a reflection of nurses' own abilities as well as their own impression of themselves. Eight nurses hope to increase or maintain their self-esteem or their value in the eyes of others and avoid guilt and anxiety.

This (showing empathy) is a responsibility that nurses should perform. A pregnant woman with a scarred uterus was advised by her doctor to have a C-section. She became very emotional and quarrelled with her doctor and husband. She listened when I talked to her, made eye contact with me and became not very emotional (Nurse 3).

If a patient is nice and I know him well, especially when the patients is my fellow townsmen, I would be proud to empathize with him (Nurse 9).

If I see that patients and their families are in pain and I do nothing or do not try hard enough, I will feel uncomfortable (Nurse 1).

(2) Subcategory 2: The possibility of tangible or intangible rewards

The nurses indicated that empathy is driven by achieving tangible or intangible rewards by a number of different ways. Eleven nurses mentioned that empathy is expressed because of the desire to receive gratitude from patients and their families and gain satisfaction and to be recognized by the leader.

A lot of patients lack knowledge (knowledge about disease); some people become autistic when they get sick, but they don't tell family what happened, and they may actually feel very bad. The family would appreciate it if you could make them understand (Nurse 2).

Sometimes I do something that doesn't satisfy the patient, so hopefully this (showing empathy) can allow her to understand us, which might improve the patient's satisfaction (Nurse 12).

The reasons for empathy are complex, and some are for future promotions (expression of indifference, dissatisfaction). Some nurses are nice to the patients in their beds but cold to the other patients. She (a nurse) only takes good care of the patients in her own beds. When the head nurse knows that she treats the patients in her beds well, she will praise and value her (Nurse 18).

(3) Subcategory 3: Avoidance of adverse effects

Some nurses show empathy to avoid adverse effects, such as medical conflicts, punishment by leaders and negative impacts on their family lives. These nurses were controlled to empathize with patients.

The current medical environment also urges us to view and understand some problems from the perspective of patients to avoid doctor-patient conflicts (Nurse 11).

In my old hospital, only punishment measures were taken and people empathized to avoid punishment (Nurse 15).

You will not be upset after work, and you will not need to worry about patients saying this or that when you are at home or when leaders call you (Nurse 3).

3) Category 3: A lack of empathy motivation

The third category is a lack of empathy motivation, which is observed when nurses lack an intention to empathize with patients and their families and do not believe in the value of empathy.

(1) Subcategory 1: A lack of intention for empathy

Three nurses mentioned that a lack of intention to show empathy occurred in nursing work. Remarkably, only one of them spoke of her own lack of empathy motivation instead of that of her colleagues.

Colleagues around me have seen and experienced too much, so they are numb and not surprised (Nurse 17).

Some colleagues have worked too long and seen too many cancer patients, so they have become emotionally numb. Although I feel pity for tumour patients, I do not empathize with them, possibly because I do not put myself in their shoes during my contact with them (Nurse 19).

(2) Subcategory 2: Denial of the value of empathy

Due to their own professional competence or professional qualities or the stress of the working environment, some nurses did not believe in the value of empathy, especially compared to routine clinical work.

Some of my colleagues feel so busy during work and think being empathetic with patients is a waste of time. It is not easy to perform the excessive workloads and make sure there are no mistakes (Nurse 13).

Sometimes, the patients' families ask the same questions repeatedly in different ways; for example, how to dispose of the patient's urine or what can the patients eat? I was the only one on the night shift and had a lot of things to do, so meeting such a family member left me really upset (Nurse 20).

DISCUSSION

We used a qualitative design to allow nurses to discuss their motivations for expressing empathy with patients. We identified three categories of empathy motivation, i.e., autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and a lack of empathy motivation, and each had corresponding subcategories. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first qualitative examination of empathy motivations among clinical nurses.

In this study, the three categories of empathy motivation, i.e., autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and a lack of empathy motivation, were identified based on self-determination theory and found to be consistent with the self-determination theory classification of motivation. Among the subcategories, “personal interest, enjoyment or a sense of value”, “assimilation”, “recognition of the importance of empathy”, “pressures from oneself and others”, “the possibility of tangible or intangible rewards”, “avoidance of adverse effects”, and “a lack of empathy motivation” are consistent with intrinsic motivation, integration regulation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation of the theory [11, 12]. In addition to these consistencies, nurses' empathetic motivations had a professional specificity that reflected the characteristics of the nursing profession. The interviews showed that love and a sense of devotion motivate the tireless empathy that these nurses have for the patient and their family and this result has not been mentioned in previous theories. This finding may be closely related to the fact that nursing is a helping profession that attracts people with certain personality traits and personal predispositions [18]. As suggested by Lombardo & Eyre [19], most nurses choose the profession under the assumption that they will be assisting patients and providing empathetic care for patients' physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual needs.

A common motivation among clinical nurses for choosing empathy with patients and their families is autonomous motivation. First, the interviews showed that some nurses spontaneously showed patients and their families understanding and care because of interest, enjoyment, a sense of value or pure altruism and asked nothing in return. Among these, pure altruism has not been mentioned in previous theories and reflects the characteristics of the nursing profession. This has been mentioned above. Second, recognition of the importance of empathy is the most frequent motive for choosing empathy. On the one hand, it suggests that nurses' empathy for patients can indeed have the important impacts, such as ensuring a good nurse-patient relationship, that have been confirmed by a large number of studies [6, 7, 8, 9]. On the other hand, it indicates that the psychological needs of nurses affect their empathy with patients. Third, several nurses talked about how they absorbed external values during their work and gradually adopted empathy as their own ideology. This reveals that the environment of the hospital and the department has a certain influence on the empathy motivation of nurses. Furthermore, according to self-determination theory, different motivation types have different effects on related variables. Compared with controlled motivation and amotivation, autonomous motivation is positively correlated with positive aspects of motivation, such as health outcomes [11]. Nursing managers, therefore, should take steps to assist nurses in maintaining a high quality of empathy motivation and select persons with career-required characteristics when recruiting nurses.

Controlled motivation is also a motivation for choosing empathy emphasized by the nurses. Nurses' empathy for the patient is accompanied by a sense of restraint or coercion without autonomy. During the interviews, one nurse explicitly considered that not empathizing with patients from the bottom of one's heart is not a real empathy. Indeed, Momaerts et al. [20] pointed out that “behaviors feigning empathy may appear disingenuous”. Furthermore, according to self-determination theory, different types of empathy motivation can be transformed into each other [11]. Thus, it is necessary for researchers and nursing management personnel to develop strategies for guiding nurses to shift from unmotivated and controlled motivation to autonomous motivation by, for example, repeatedly engaging in autonomously motivating activities [21]. In other words, optimizing the type of empathy motivation is necessary to improve the empathy-based care ability among nurses. In addition, college educators should consider adding empathy motivation to the curriculum to cultivate students' empathy caretaking ability at an early stage.

According to the study, several nurses were described as not attempting to help others or provide empathetic care, regardless of the severity of the patients' condition. These nurses believed that some of their colleagues had become emotionally numb because of experiencing or seeing too much, especially nurses who provided care to cancer patients. As healthcare providers, empathetic and caring nurses experience long-term and frequent exposure to patients' traumatic events, especially those of cancer patients and their family members. However, when the difficulty of such exposure is not acknowledged and the appropriate steps are not taken to manage the situation, such nurses can become victims of the continuing stress of meeting patients' needs; in other words, they can experience psychological distress [22] that leads to compassion fatigue [10, 19, 23]. In addition, there is a shortage of nursing staff in China and nurses experience heavy workloads; thus, time at work is precious. Time pressure has a negative impact on nurses' empathy towards patients and their families since increases the difficulty of expressing empathy [10, 24]. Some nurses working in this environment may even think that being empathetic with patients is a waste of time when they are not treated with trust or respect, which is consistent with the results of other studies [25]. Thus, elements that make nursing empathy more inherently enjoyable and beneficial consequences must first be secured by nurse leaders, and those nursing leaders should then ensure that the working environment allows nurses to satisfy certain innate psychological needs, namely, the need for autonomy [22, 26], to support the development of empathy motivations and thereby improve the nurses' professional competence and performance.

This study had several limitations. Participants were recruited from just four tertiary hospitals in Anhui Province. Because empathetic motivations may vary across different regions and hospital levels, the generalizability of the results to other nursing contexts is limited. In addition, the sample may not represent all nurses working in the above hospitals because the participants were volunteers. Therefore, the nurses participating in our study may have tended to be empathetic. To reduce bias, we asked the participants how their colleagues and leaders thought about empathy motivation.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to explore clinical nurses' motivations for empathy within the theoretical framework of self-determination theory and provided an opportunity to understand clinical nurses' reasons for empathizing with patients and their family members. Clinical nurses are motivated to empathize with patients based on a variety of factors and different combinations of motivation types. In addition, the three categories of empathy motivation are consistent with the self-determination theory and reflect the characteristics of nursing professional culture. Nurse management should be encouraged to emphasize to plan effective strategies to provide an empathetic care culture. In other words, strategies to shift from unmotivated and controlled motivation to autonomous motivation should be developed. Also management should focus on factors in the organizational environment that have impacts on motivation experiences.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:The authors declared no conflict of interest.

FUNDING:This study was supported by the Domestic and Foreign Research Projects for Outstanding Young Backbone Talents in Universities of Anhui Province (NO. gxfx2017047) and Scientific Research Foundation of the Department of Education of Anhui Province (NO. KJ2019A0460).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: Zhu Y.

Data curation or/and Analysis: Zhu Y & He MM.

Funding acquisition: Li BK.

Investigation: Zhu Y & He MM.

Project administration or/and Supervision: Li BK & Zhu JM.

Resources or/and Software: Zhu Y.

Validation: Li BK.

Visualization: Huang L.

Writing original draft or/and Review & editing: Zhu Y & Li BK.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

References

-

Hojat M. In: Empathy in patient care: Antecedents, development, measurement, and outcomes. New York (NY): Springer; 2007. pp. 67.

-

-

Zhu Y, Zhan YC, Zhu JM, Huang L, Zhang L, Zhang M, et al. The development and psychometric validation of a Chinese empathy motivation scale. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2019;28(13-14):2599–2612. [doi: 10.1111/jocn.14846]

-

-

Dor A, Mashiach Eizenberg M, Halperin O. Hospital nurses in comparison to community nurses: Motivation, empathy, and the mediating role of burnout. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 2019;51(2):72–83. [doi: 10.1177/0844562118809262]

-

-

Dambha-Miller H, Feldman AL, Kinmonth AL, Griffin SJ. Association between primary care practitioner empathy and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes: A population-based prospective cohort study. Annals of Family Medicine 2019;17(4):311–318. [doi: 10.1370/afm.2421]

-

-

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000;11(4):227–268. [doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01]

-

-

Munhall PL. In: Nursing research: A qualitative perspective. 4th ed. Sudbury (MA): Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2007. pp. 86.

-

-

Kluczyńska U. Motives for choosing and resigning from nursing by men and the definition of masculinity: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2017;73(6):1366–1376. [doi: 10.1111/jan.13240]

-

-

Lombardo B, Eyre C. Compassion fatigue: A nurse’s primer. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 2011;16(1):3 [doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01Man03]

-

-

Ashouri E, Taleghani F, Memarzadeh M, Saburi M, Babashahi F. The perceptions of nurses, patients and family members regarding nurses’ empathetic behaviours towards patients suffering from cancer: A descriptive qualitative study. Journal of Research in Nursing 2018;23(5):428–443. [doi: 10.1177/1744987118756945]

-

-

Baard PP, Neville SM. The intrinsically motivated nurse. Help and hindrance from evaluation feedback sessions. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1996;26(7-8):19–26. [doi: 10.1097/00005110-199607000-00007]

-

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite