Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Nurs > Volume 45(6); 2015 > Article

-

Original Article

- Factors Influencing Posttraumatic Growth in Fathers of Chronically ill Children

- Mi Young Kim

-

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2015;45(6):890-899.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2015.45.6.890

Published online: December 15, 2015

College of Nursing, Eulji University, Seongnam, Korea

College of Nursing, Eulji University, Seongnam, Korea

- Address reprint requests to : Kim, Mi Young College of Nursing, Eulji University, 553 Sanseong-daero, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam 13135, Korea Tel: +82-31-740-7398 Fax: +82-31-740-7359 E-mail: kimmy@eulji.ac.kr

• Received: June 4, 2015 • Revised: June 17, 2015 • Accepted: September 15, 2015

Copyright © 2015 Korean Society of Nursing Science

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivs License. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0) If the original work is properly cited and retained without any modification or reproduction, it can be used and re-distributed in any format and medium.

Abstract

-

Purpose

- The purpose of this study was to identify the level of distress and posttraumatic growth in fathers of chronically ill children and also, to identify the relation between characteristics of the fathers and children and their posttraumatic growth and to investigate factors that influence posttraumatic growth.

-

Methods

- In this study, 48 fathers who visited a university hospital in Seoul, Korea and who gave written consent completed the questionnaire between September 23 and November 19, 2013. Data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, Pearson correlation coefficient and stepwise multiple regression.

-

Results

- The level of distress in fathers of chronically ill children was relatively high and the majority of them were experiencing posttraumatic growth. Models including the variable (deliberate rumination, religiousness, optimism) explained 64.3% (F=26.38, p< .001) of the variance for posttraumatic growth. Deliberate rumination (β=.59, p< .001) was the most influential factor.

-

Conclusion

- The findings demonstrate that it is essential for nurses to intervene and facilitate continuously so as to promote posttraumatic growth and relieve distress in fathers of chronically ill children. Furthermore, it is also necessary for nurses to find ways to develop ideal interventions to activate deliberate rumination and offer spiritual care and help maintain optimism in these individuals.

Table 1.Posttraumatic Growth according to the General Characteristics of Father and Child and Characteristics related Child’s Disease(N=48)

| Variables | Categories | n (%) or M±SD |

Posttraumatic growth |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | Median [Min, Max] | p | |||

| Fathers’ age (yr) | 25~34 | 9 (18.8) | 48.33± 17.68 | 53.0 [11, 69] | .248* |

| 35~44 | 29 (60.4) | 46.69± 18.02 | 43.0 [17, 79] | ||

| 45~54 | 10 (20.8) | 57.90± 9.48 | 60.0 [42, 74] | ||

| 40.73± 5.77 | |||||

| Level of education | ≤High school | 13 (27.1) | 51.00± 13.98 | 53.0 [11, 79] | .871† |

| ≥College | 35 (72.9) | 48.71± 17.95 | 51.0 [29, 72] | ||

| Employment (at diagnosis) | Employed | 47 (97.9) | 49.98±16.42 | 52.0 [11, 79] | .125* |

| Not employed | 1 (2.1) | 19.00 | 19.0 | ||

| Employment (current) | Employed | 34 (70.8) | 50.03±16.93 | 53.5 [17, 79] | .610† |

| Not employed | 14 (29.2) | 47.64±17.17 | 50.0 [11, 74] | ||

| Burden of medical care costs | None at all or hardly any | 7 (14.6) | 40.57±19.72 | 41.0 [11, 62] | .226* |

| Moderately | 12 (25.0) | 46.67±17.81 | 46.0 [19, 79] | ||

| Very high | 16 (33.3) | 50.13±13.31 | 51.0 [29, 70] | ||

| Extremely high | 13 (27.1) | 55.54±17.63 | 58.0 [17, 74] | ||

| Religion | Yes | 30 (62.5) | 55.67±15.09 | 59.0 [17, 79] | .001† |

| No | 18 (37.5) | 38.78±14.70 | 41.0 [11, 66] | ||

| Child’s age (yr) | 0~2 | 11 (22.9) | 52.00±13.60 | 53.0 [29, 70] | .239* |

| 3~6 | 8 (16.7) | 35.25±21.26 | 27.5 [11, 70] | ||

| 7~12 | 15 (31.3) | 52.47±15.87 | 52.0 [27, 79] | ||

| ≥13 | 14 (29.1) | 51.93±14.93 | 54.0 [17, 74] | ||

| 8.67±5.81 | |||||

| Child’s gender | M | 31 (64.6) | 48.90±16.00 | 51.0 [11, 74] | .746† |

| F | 17 (35.4) | 50.12±18.80 | 52.0 [17, 79] | ||

| Child’s birth order | 1st or only child | 33 (68.8) | 49.03±16.52 | 51.0 [11, 79] | .772† |

| ≥2nd | 15 (31.2) | 50.00±18.14 | 52.0 [19, 74] | ||

| Child’s age at diagnosis (yr) | 0~2 | 18 (37.5) | 49.39±17.27 | 51.5 [11, 70] | .829* |

| 3~6 | 11 (22.9) | 45.55±17.21 | 50.0 [19, 72] | ||

| 7~15 | 19 (39.6) | 51.47±16.78 | 56.0 [17, 79] | ||

| 5.60±4.59 | |||||

| Duration of illness | 3 months -1yr | 20 (41.7) | 46.35±15.31 | 46.0 [19, 69] | .668* |

| 1~3 yr | 12 (25.0) | 50.50±24.05 | 57.5 [11, 79] | ||

| 3~5 yr | 7 (14.6) | 50.43±11.84 | 51.0 [35, 70] | ||

| > 5 yr | 9 (18.7) | 53.56±12.88 | 52.0 [29, 69] | ||

| 3.16±4.10 | |||||

| Child’s diagnosis | Leukemia | 15 (31.3) | 50.93±15.45 | 52.0 [19, 74] | .621* |

| Brain tumor | 6 (12.5) | 46.83±19.90 | 50.5 [17, 69] | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 6 (12.5) | 40.83±19.93 | 43.5 [11, 66] | ||

| Others | 21 (43.7) | 51.33±16.50 | 53.0 [20, 79] | ||

Table 2.Posttraumatic Growth according to Fathers’ Distress and Perception of Psychological Growth (N=48)

| Variables | Categories | n (%) or M±SD |

Posttraumatic growth |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | Median [Min, Max] | p | |||

| Fathers’distress | Less than usual distress (≤3) | 1 (2.1) | 50.00 | 50.0 | .800† |

| (at diagnosis) | More than usual distress (≥4) | 47 (97.9) | 49.32±17.03 | 52.0 [11, 79] | |

| (range 0~7) | 6.71±0.71 | ||||

| Fathers’ distress | Less than usual distress (≤3) | 6 (12.5) | 57.83±7.60 | 57.5 [50, 70] | .249† |

| (current) | More than usual distress (≥4) | 42 (87.5) | 48.12±17.50 | 51.5 [11, 79] | |

| (range 0~7) | 4.81±1.39 | ||||

| Fathers’ alleviation | Not alleviated | 11 (22.9) | 55.09±15.68 | 56.0 [17, 74] | .155† |

| of distress | Alleviated | 37 (77.1) | 47.62±17.01 | 50.0 [11, 79] | |

| Acceptable | Yes | 45 (93.7) | 61.67±7.51 | 51.0 [11, 79] | .147† |

| No | 3 (6.3) | 48.51±17.02 | 62.0 [54, 69] | ||

| Positive changes due | Yes | 43 (89.6) | 50.86±16.75 | 53.0 [11, 79] | .041† |

| to child’s illness | No | 5 (10.4) | 36.20±12.19 | 41.0 [19, 50] | |

| Experienced | Yes | 47 (97.9) | 49.77±16.76 | 52.0 [11, 79] | .220† |

| psychological growth | No | 1 (2.1) | 29.00 | 29.0 | |

| The point at which | ≤1 | 42 (87.5) | 48.62±16.82 | 51.5 [11, 79] | .188* |

| psychological growth | ≤2 | 2 (4.2) | 52.00±24.04 | 52.0 [35, 69] | |

| began (yr) | Don’t know | 3 (6.3) | 64.33±4.93 | 62.0 [61, 70] | |

| Not yet | 1 (2.0) | 29.00 | 29.0 | ||

| 6.00±5.74 months | |||||

Table 3.Mean Scores and Correlations for Posttraumatic Growth, Optimism, Disruption of Core Beliefs, Deliberate Rumination, Social Support(N=48)

Table 4.Multiple Regression Analysis of Father’s Posttraumatic Growth (N=48)

| Variables | B | SE | β t (p) |

Collinearity statistics |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Deliberate rumination | 2.11 | 0.34 | .59 6.25 (<.001) | .92 | 1.07 |

| Religion* | 10.51 | 3.27 | .31 3.22 (.002) | .90 | 1.10 |

| Optimism | 1.21 | 0.53 | .21 2.27 (.028) | .91 | 1.09 |

| R2=.64, F=26.38, p<.001 | |||||

- 1. Han KJ, Kwon MK, Bang KS. Parent-child health and nursing. Seoul: Hyunmoon; 2010.

- 2. Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The foundation of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. p. 3–23.

- 3. Kim Y, Schulz R, Carver CS. Benefit-finding in the cancer caregiving experience. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(3):283–291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180417cf4ArticlePubMed

- 4. Cho YK. The change of social structure and fathering in South Korea. Korean Journal of Converging Humanities. 2014;2(1):83–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.14729/converging.k.2014.2.1.83Article

- 5. Dashiff C, Morrison S, Rowe J. Fathers of children and adolescents with diabetes: What do we know? Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2008;23(2):101–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2007.08.007ArticlePubMed

- 6. Kim J, Yun HJ. A study on the parenting experiences of fathers of children with disabilities. Special Education Research. 2013;12(3):333–356.Article

- 7. Hwang EJ. Experience of fathers raising children with disabilities: Conflicts, difficulties and positive changes [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Chung Ang University; 2014.

- 8. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305ArticlePubMed

- 9. Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(1):11–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7eArticlePubMed

- 10. Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20(1):20–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.20.1.20PubMed

- 11. Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Kilmer RP, Gil-Rivas V, Vish-nevsky T, et al. The core beliefs inventory: A brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety Stress and Coping. 2010;23(1):19–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615800802573013ArticlePubMed

- 12. Thornton AA, Perez MA. Posttraumatic growth in prostate cancer survivors and their partners. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(4):285–296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.953ArticlePubMed

- 13. Hungerbuehler I, Vollrath ME, Landolt MA. Posttraumatic growth in mothers and fathers of children with severe illnesses. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(8):1259–1267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105311405872ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Song SH, Lee HS, Park JH, Kim KH. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. The Korean Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(1):193–214.Article

- 16. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(6):1063–1078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063ArticlePubMed

- 17. Shin H. Testing the mediating effect of coping in the relation of optimism and pessimism to psychological adjustment in adolescents. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2005;12(3):165–192.

- 18. Jo SM. The causal relationship of cognitive factors, social support and resilience on youth’s posttraumatic growth [master’s thesis]. Busan: Pusan National University; 2012.

- 19. Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Triplett KN, Vishnevsky T, Lindstrom CM. Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: The event related rumination inventory. Anxiety Stress and Coping. 2011;24(2):137–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2010.529901ArticlePubMed

- 20. Ahn HN, Joo HS, Min JW, Sim KS. Validation of the event related rumination inventory in a Korean population. Cognitive Behavior Therapy in Korea. 2013;13(1):149–172.

- 21. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2Article

- 22. Shin JS, Lee YB. The effects of social supports on psychosocial well-being of the unemployed. Korean Journal of Social Welfare. 1999;37:241–269.

- 23. Polatinsky S, Esprey Y. An assessment of gender differences in the perception of benefit resulting from the loss of a child. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13(4):709–718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/a:1007870419116ArticlePubMed

- 24. Vishnevsky T, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Demakis GJ. Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34(1):110–120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01546.xArticlePDF

- 25. Yi GO, Han SH, Park HJ. Changes and growth among families of children with disabilities: Based on child-rearing experiences of mothers and fathers. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 2010;26(4):137–163.

- 26. Bonner MJ, Hardy KK, Willard VW, Hutchinson KC. Brief report: Psychosocial functioning of fathers as primary caregivers of pediatric oncology patients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(7):851–856. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm011ArticlePubMed

- 27. Davies B, Gudmundsdottir M, Worden B, Orloff S, Sumner L, Brenner P. “Living in the dragon’s shadow” fathers’ experiences of a child's life-limiting illness. Death Studies. 2004;28(2):111–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07481180490254501ArticlePubMed

- 28. Shin SY, Chung NW. The effect of meaning in life and social support on posttraumatic growth: Rumination as a mediating variable. Journal of Human Understanding and Counseling. 2012;33(2):217–235.

- 29. Park H, Ahn H. The effects of posttraumatic stress symptoms, spirituality, and rumination on posttraumatic growth. The Korea Journal of Counseling. 2006;7(1):201–214.

- 30. Yoo YS, Cho OH, Cha KS, Boo YJ. Factors influencing post-traumatic stress in Korean forensic science investigators. Asian Nursing Research. 2013;7(3):136–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.07.002ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- A sense of coherence (SOC) among the fathers of children with chronic illnesses

Masahiro Haraguchi, Tomoko Takeuchi

Nursing Open.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Relationship between mental health and stressors among fathers of children with chronic illnesses and cognitive structure of fathers’ stress experiences

Masahiro Haraguchi

Scientific Reports.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - The Relationship between Post-Traumatic Growth, Trauma Experience and Cognitive Emotion Regulation in Nurses

Sook Lee, Mun Gyeong Gwon, YeonJung Kim

Korean Journal of Stress Research.2018; 26(1): 31. CrossRef - Shifting of Centricity: Qualitative Meta Synthetic Approach on Caring Experience of Family Members of Patients with Dementia

Young Mi Ryu, Mi Yu, Seieun Oh, Haeyoung Lee, Haejin Kim

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing.2018; 48(5): 601. CrossRef - Predictors of the Posttraumatic Growth in Parents of Children with Leukemia

Sungsil Hong, Ho Ran Park, Sun Hee Choi

Asian Oncology Nursing.2018; 18(4): 224. CrossRef - Perception on Parental Coping on Unintentional Injury of Their Early Infants and Toddlers: Q Methodological Approach

Da In Lee, Ho Ran Park, Sun Nam Park, Sungsil Hong

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing.2018; 48(3): 335. CrossRef

Factors Influencing Posttraumatic Growth in Fathers of Chronically ill Children

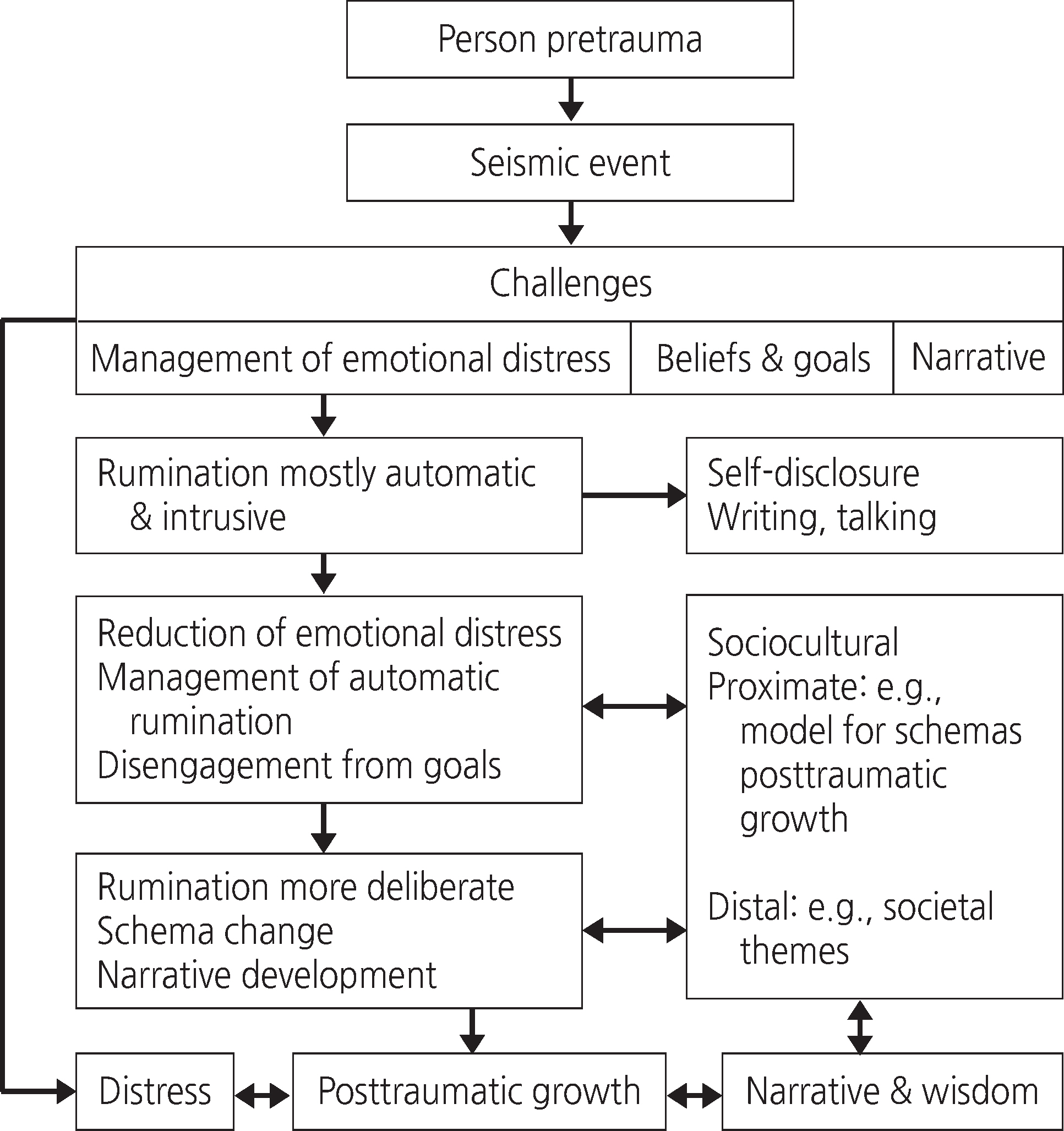

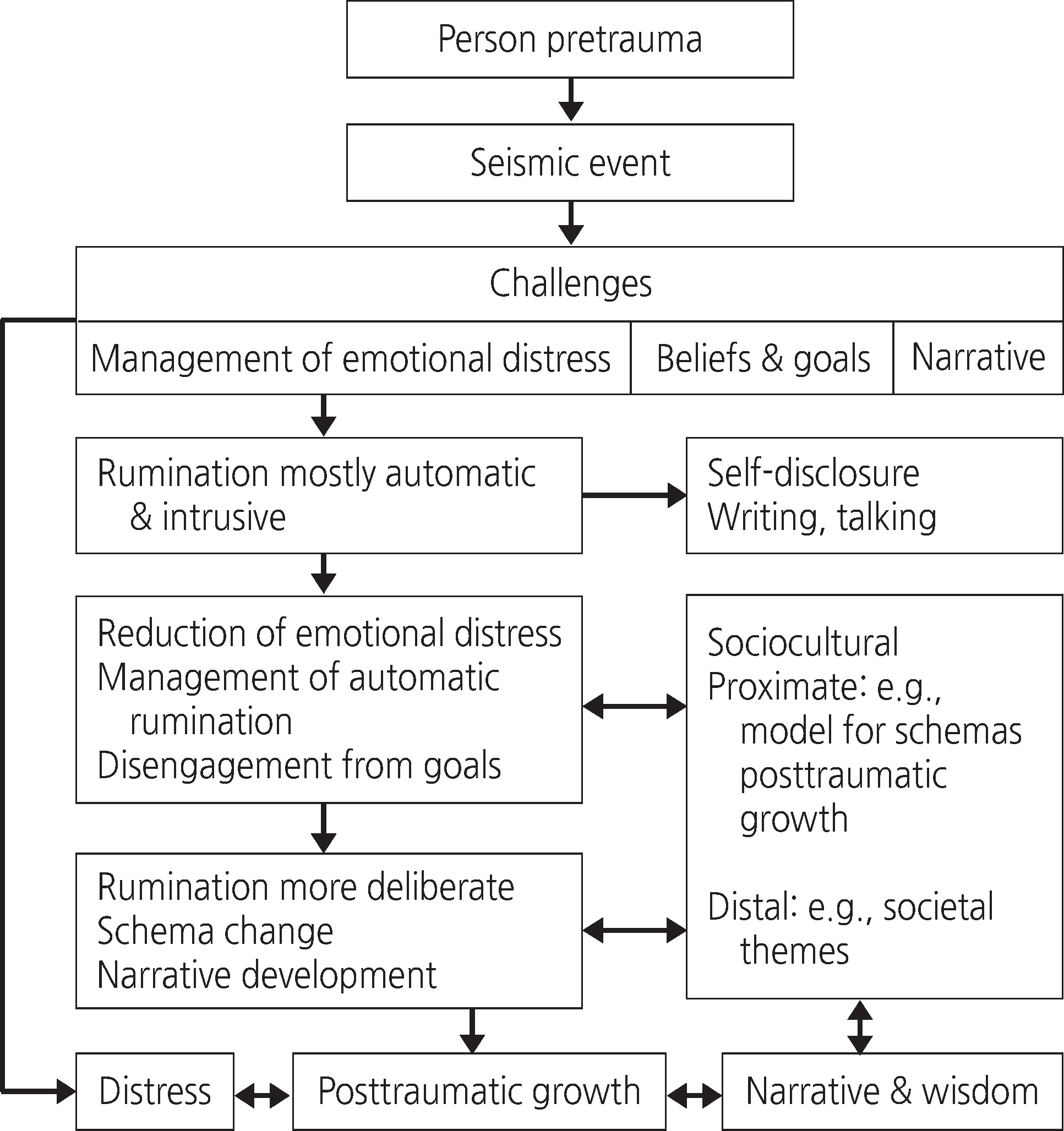

Figure 1. A Theoretical Model of Posttraumatic Growth Model by Calhoun & Tedeschi (2006).

Figure 1.

Factors Influencing Posttraumatic Growth in Fathers of Chronically ill Children

| Variables | Categories | n (%) or M±SD | Posttraumatic growth |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | Median [Min, Max] | p | |||

| Fathers’ age (yr) | 25~34 | 9 (18.8) | 48.33± 17.68 | 53.0 [11, 69] | .248 |

| 35~44 | 29 (60.4) | 46.69± 18.02 | 43.0 [17, 79] | ||

| 45~54 | 10 (20.8) | 57.90± 9.48 | 60.0 [42, 74] | ||

| 40.73± 5.77 | |||||

| Level of education | ≤High school | 13 (27.1) | 51.00± 13.98 | 53.0 [11, 79] | .871 |

| ≥College | 35 (72.9) | 48.71± 17.95 | 51.0 [29, 72] | ||

| Employment (at diagnosis) | Employed | 47 (97.9) | 49.98±16.42 | 52.0 [11, 79] | .125 |

| Not employed | 1 (2.1) | 19.00 | 19.0 | ||

| Employment (current) | Employed | 34 (70.8) | 50.03±16.93 | 53.5 [17, 79] | .610 |

| Not employed | 14 (29.2) | 47.64±17.17 | 50.0 [11, 74] | ||

| Burden of medical care costs | None at all or hardly any | 7 (14.6) | 40.57±19.72 | 41.0 [11, 62] | .226 |

| Moderately | 12 (25.0) | 46.67±17.81 | 46.0 [19, 79] | ||

| Very high | 16 (33.3) | 50.13±13.31 | 51.0 [29, 70] | ||

| Extremely high | 13 (27.1) | 55.54±17.63 | 58.0 [17, 74] | ||

| Religion | Yes | 30 (62.5) | 55.67±15.09 | 59.0 [17, 79] | .001 |

| No | 18 (37.5) | 38.78±14.70 | 41.0 [11, 66] | ||

| Child’s age (yr) | 0~2 | 11 (22.9) | 52.00±13.60 | 53.0 [29, 70] | .239 |

| 3~6 | 8 (16.7) | 35.25±21.26 | 27.5 [11, 70] | ||

| 7~12 | 15 (31.3) | 52.47±15.87 | 52.0 [27, 79] | ||

| ≥13 | 14 (29.1) | 51.93±14.93 | 54.0 [17, 74] | ||

| 8.67±5.81 | |||||

| Child’s gender | M | 31 (64.6) | 48.90±16.00 | 51.0 [11, 74] | .746 |

| F | 17 (35.4) | 50.12±18.80 | 52.0 [17, 79] | ||

| Child’s birth order | 1st or only child | 33 (68.8) | 49.03±16.52 | 51.0 [11, 79] | .772 |

| ≥2nd | 15 (31.2) | 50.00±18.14 | 52.0 [19, 74] | ||

| Child’s age at diagnosis (yr) | 0~2 | 18 (37.5) | 49.39±17.27 | 51.5 [11, 70] | .829 |

| 3~6 | 11 (22.9) | 45.55±17.21 | 50.0 [19, 72] | ||

| 7~15 | 19 (39.6) | 51.47±16.78 | 56.0 [17, 79] | ||

| 5.60±4.59 | |||||

| Duration of illness | 3 months -1yr | 20 (41.7) | 46.35±15.31 | 46.0 [19, 69] | .668 |

| 1~3 yr | 12 (25.0) | 50.50±24.05 | 57.5 [11, 79] | ||

| 3~5 yr | 7 (14.6) | 50.43±11.84 | 51.0 [35, 70] | ||

| > 5 yr | 9 (18.7) | 53.56±12.88 | 52.0 [29, 69] | ||

| 3.16±4.10 | |||||

| Child’s diagnosis | Leukemia | 15 (31.3) | 50.93±15.45 | 52.0 [19, 74] | .621 |

| Brain tumor | 6 (12.5) | 46.83±19.90 | 50.5 [17, 69] | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 6 (12.5) | 40.83±19.93 | 43.5 [11, 66] | ||

| Others | 21 (43.7) | 51.33±16.50 | 53.0 [20, 79] | ||

| Variables | Categories | n (%) or M±SD | Posttraumatic growth |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M±SD | Median [Min, Max] | p | |||

| Fathers’distress | Less than usual distress (≤3) | 1 (2.1) | 50.00 | 50.0 | .800 |

| (at diagnosis) | More than usual distress (≥4) | 47 (97.9) | 49.32±17.03 | 52.0 [11, 79] | |

| (range 0~7) | 6.71±0.71 | ||||

| Fathers’ distress | Less than usual distress (≤3) | 6 (12.5) | 57.83±7.60 | 57.5 [50, 70] | .249 |

| (current) | More than usual distress (≥4) | 42 (87.5) | 48.12±17.50 | 51.5 [11, 79] | |

| (range 0~7) | 4.81±1.39 | ||||

| Fathers’ alleviation | Not alleviated | 11 (22.9) | 55.09±15.68 | 56.0 [17, 74] | .155 |

| of distress | Alleviated | 37 (77.1) | 47.62±17.01 | 50.0 [11, 79] | |

| Acceptable | Yes | 45 (93.7) | 61.67±7.51 | 51.0 [11, 79] | .147 |

| No | 3 (6.3) | 48.51±17.02 | 62.0 [54, 69] | ||

| Positive changes due | Yes | 43 (89.6) | 50.86±16.75 | 53.0 [11, 79] | .041 |

| to child’s illness | No | 5 (10.4) | 36.20±12.19 | 41.0 [19, 50] | |

| Experienced | Yes | 47 (97.9) | 49.77±16.76 | 52.0 [11, 79] | .220 |

| psychological growth | No | 1 (2.1) | 29.00 | 29.0 | |

| The point at which | ≤1 | 42 (87.5) | 48.62±16.82 | 51.5 [11, 79] | .188 |

| psychological growth | ≤2 | 2 (4.2) | 52.00±24.04 | 52.0 [35, 69] | |

| began (yr) | Don’t know | 3 (6.3) | 64.33±4.93 | 62.0 [61, 70] | |

| Not yet | 1 (2.0) | 29.00 | 29.0 | ||

| 6.00±5.74 months | |||||

| Variables | M±SD | Posttraumatic growth |

Optimism |

Disruption of core beliefs |

Deliberate rumination |

Social support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | ||

| Posttraumatic growth | 49.33±16.85 | 1.00 | .41 (.002) | .49 (<.001) | .69 (<.001) | .48 (<.001) |

| Optimism | 16.58±2.98 | 1.00 | .21 (.074) | .19 (.090) | .35 (.008) | |

| Disruption of core beliefs | s 27.10±8.16 | 1.00 | .48 (<.001) | .43 (.001) | ||

| Deliberate rumination | 20.33±4.67 | 1.00 | .41 (.002) | |||

| Social support | 63.06±11.91 | 1.00 |

| Variables | B | SE | β t (p) | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Deliberate rumination | 2.11 | 0.34 | .59 6.25 (<.001) | .92 | 1.07 |

| Religion |

10.51 | 3.27 | .31 3.22 (.002) | .90 | 1.10 |

| Optimism | 1.21 | 0.53 | .21 2.27 (.028) | .91 | 1.09 |

| R2=.64, F=26.38, p<.001 | |||||

Table 1. Posttraumatic Growth according to the General Characteristics of Father and Child and Characteristics related Child’s Disease(N=48)

Kruskal-Wallis test; Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2. Posttraumatic Growth according to Fathers’ Distress and Perception of Psychological Growth (N=48)

Kruskal-Wallis test; Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 3. Mean Scores and Correlations for Posttraumatic Growth, Optimism, Disruption of Core Beliefs, Deliberate Rumination, Social Support(N=48)

Table 4. Multiple Regression Analysis of Father’s Posttraumatic Growth (N=48)

Dummy variable; Religion: Yes=1, No=0; VIF=Variation inflation factor.

KSNS

KSNS

E-SUBMISSION

E-SUBMISSION

Cite

Cite